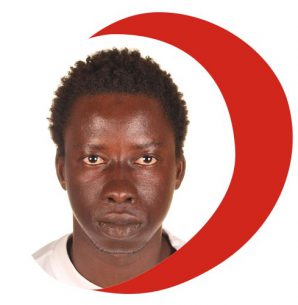

When Mamadi Susso left the Gambia in 2015 at age 19, he was fleeing a dictatorship and tough economic conditions. Jobs and opportunities for youth in the West African nation are rare, and many people can’t depend on having regular meals.

With a dream of becoming an entrepreneur, Susso risked the dangerous journey across the desert and the sea in search of work opportunities abroad.

“I decided to take the risk to travel to Europe through the back way in order to take my family out of extreme poverty,” he says, a phrase Gambians use for irregular migration routes.

After spending three months in Italy, Susso arrived in the summer of 2016 in the southwestern German town of Weinheim, where he applied for asylum.

“I came from a very humble background, where it was very difficult to cater for regular meals,” says Susso, who represented his village in football tournaments and had dreamed of becoming a professional footballer. Now 24, he has a wide smile and just plays football for fun. “My dream is to build a good house for my family and to establish a viable transportation business in the Gambia.”

Susso was born into a family in a village called Saruja, far inland from the Gambian capital, Banjul. Saruja has a population of just under 2,000 and used to be a rice-growing powerhouse but has seen a shift to vegetable gardening because rice farming doesn’t return the profits it used to.

The Gambia is the smallest country in mainland Africa, slightly larger than Lebanon. The former British colony occupies a long narrow strip of land that stretches 450km along the River Gambia, which divides the country into two parts — the North and South banks. The country is surrounded by neighboring Senegal on all three sides, except to the west, where the 60km coastline kisses the Atlantic Ocean.

The Gambia has a $1 billion economy which relies upon three main aspects: agriculture, tourism and remittances. The number of migrants from The Gambia has grown from 77,440 in 2010 to 139,210 in 2020, according to U.N. data — that’s about 6% of the country’s total population of 2.3 million. More than 85,000 of these Gambians live in Europe, and 15,535 of them in Germany.

People have become the most important export for this small, poor and highly indebted nation. The Gambian diaspora’s remittances directly finance feeding, health care, education, housing needs and small-scale enterprises for the entire country, accounting for 48% of the country’s gross domestic product in 2020. Remittances reached a record high of $578.5 million last year, despite the pandemic.

The struggle

When Libya was an economically prosperous nation, many Gambians and other West African migrants lived and worked there. But when civil war broke out in 2011, many of these migrants felt unsafe there and tried to cross the Mediterranean to Italy.

Susso’s journey started with a bus from Banjul to the Senegalese capital Dakar. From there another bus to Bamako in Mali, to Ouagadougou in Burkina Faso and to Agadez in Niger. From Niger, he crossed the desert to reach Libya. The journey from the Libyan shore to southern Italy lasted three days, and eventually, Susso and about 150 other men and women were rescued by the Italian coast guard and sent to a refugee camp in Bologna.

Over the past decade, tens of thousands of Gambians have taken the Central Mediterranean route to Europe in search of a safe refuge and better economic conditions. Many of them, after entering via Italy, traveled on to Germany, as Susso did.

Before he left the Gambia, Susso had only attained a junior secondary school certificate and was scraping together a living as a painter in one of the poorest districts, Lower Fulladu West, where more than 80% of the population of 40,481 were living on less than $1.25 dollars a day in 2019, according to GBoS data.

The Gambia is generally a poor country, with a national poverty rate of nearly 50%. Poverty is more severe in rural areas, where close to 70% of the population are poor, with urban poverty just over 30%. And about a third of the population are unemployed, according to the UNDP. The UNDP’s 2020 Human Development Index ranks the country at 172 out of 189 countries worldwide.

Many Gambians who now live and work in Europe and America were not just fleeing poor economic conditions but also a 22-year dictatorship. Although the political situation has become more stable, the Gambia’s economy keeps taking hard hits. Agricultural production has seen a significant decline in recent years, and the country’s tourism industry is projected to lose up to $292 million as a result of the devastating impact of the coronavirus pandemic.

Susso worked in a restaurant for a year and half after he arrived in Germany, and now works in the warehouse of a timber processing company.

His painting job in the Gambia only yielded occasional jobs with very minimal financial rewards. He was living hand to mouth, he says. But in Germany, Susso earns €10 per hour — just above minimum wage — and works regular hours from Monday to Friday, earning on average €1,600 a month.

Safety nets

In most Gambian settings, traditional values place much emphasis on the extended family. As a result, it is common for one employed or diaspora-based person in the family to provide for other relatives. This serves as a social safety net for children, the elderly and the unemployed in a country where social protection mechanisms are weak and unavailable to most citizens.

Susso’s father, two elder brothers and a sister have died, putting more pressure on him as an earner. He sends on average €200 to his family in the Gambia each month.

That’s equal to 12,430 Gambian dalasi, equal to about $240 and six times higher than the monthly salary of a person with an entry-level government job. It’s enough to pay the rent for a standard three-bedroom house outside the capital for three months. For Susso’s family, which has a house in the village, the sum can take care of all of the food, health care and water bills for a month.

Susso sends the money from Germany via Western Union or MoneyGram to his cousin, Sarjo Kongira.

“Mamadi Susso is my cousin, and I manage his transport business and receive monies he is sending on behalf of his family,” says Kongira, a man of few words. But he’s a keen observer who likes helping people by sharing the little he has.

Susso’s remittances go towards feeding, education and health care for his mother, younger brother, and the six children left behind by his late brothers.

The Gambia is one of the most difficult places to do business, according to the World Bank. For example, while it can take half a day to register a firm in New Zealand, in the Gambia the process takes up to eight days and involves getting documents from various government offices in different locations. Electricity supply is also unreliable, and small enterprises do not have access to bank loans.

Despite the challenges, Susso was able to start a small transportation business by shipping a 27-seat Mercedes van from Germany. Kongira manages the vehicle, which transports passengers from Serekunda to Brikamaba, the town closest to their village. A single trip can yield GMD 5,400, about $105.

The business started fairly well in 2019, with up to GMD 40,000 in savings a month, Kongira says. But earnings dropped significantly in 2020 after the government set passenger limits to minimize the spread of Covid-19.

Despite this setback, Susso employs a driver and an apprentice, and plans to ship more cars to expand his transport business once his status is regularized in Germany.

“Susso’s travel to Europe has really changed his life and that of his family in all aspects,” Kongira says with a smile.

Years ago, Kongira would host Susso whenever he left the village for short visits to Serekunda. The two grew up in the same village, playing football together and brewing green tea. Today Susso keeps in touch with his Gambian family via the messaging platform WhatsApp.

He is solely in charge of the family’s welfare.

Susso has been able to pay for a perimeter fence around his mother’s compound in the village. “He is solely in charge of the family’s welfare,” says Kongira, who now lives in the resort town of Kololi on the Atlantic coast.

Susso’s family, like most rural residents of Gambia’s central river region, are rice farmers. But a lack of modern farming tools and changing climatic conditions means they hardly are able to produce enough for themselves and for sale.

His family is now among over 122,000 households in the Gambia whose lives and livelihoods are almost entirely dependent on remittances, according to the Integrated Household Survey.

“The Gambians in diaspora are really trying to create meaningful social and economic changes for their people via remittances,” Kongira says generally. “It won’t be easy to live here without the impactful role of diaspora remittances, because almost all the families in this country are relying on them.”

Surprising surge of support

In April 2020, the World Bank indicated that remittances were estimated to fall by about 28% in 2020 due to the combined effects of the global coronavirus pandemic and lower oil prices. But the Gambia actually experienced a surge in remittances, reaching a record high of $578.5 million in 2020 from $329.8 million in 2019.

The increase in remittances volume has been largely driven by the Covid-19 restrictions and an improved remittance data recording system, according to the Central Bank of The Gambia. Travel restrictions forced informal remittances to go through formal remittance channels, the Bank’s first deputy governor, Seeku Jaabi, said in a forum on Gambia’s Diaspora Strategy in January.

Most Gambian migrants and asylum seekers in Germany live in Baden-Württemberg, the same state as Susso, whose asylum application was denied. Susso said he is not sure why. He took German language courses for a year and has a steady job. But he now has a document saying his deportation is suspended and his presence in the country is “tolerated.”

In Baden-Württemberg, Susso is married to an Ethiopian he met in Weinheim, and together they have two children, a 2-year-old boy and a 1-year-old girl. He is hopeful that his steady job and familial ties will one day win him permanent residency status.

“I have exhausted all my asylum application chances,” Susso says. “However, all my children are documented along with their mother, whose asylum has been granted. So I am hopeful that I will have documents to stay in Germany for that sake.”

Despite this setback on his dream of a better life, Susso likes Germany as a place to live and work. “I am motivated [to be here] and will always respect the country’s laws at all times and keep a positive attitude no matter what comes my way,” he says. “I’m encouraged by an adage that every successful man will always have a story to tell others.”

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.