Many years ago, I worked as an assistant editor at a genealogy magazine in Cincinnati. We helped family researchers find their roots, which in the U.S. often meant figuring out when and how their ancestors left the “old country.” The further back that journey happened, the more obscured the reasons for leaving would be.

Immigration boils down to push and pull factors. Some people move because they need a better place to live, like refugees trying to escape war or famine. And then there are pull factors — the shining lights of a city of opportunity, perhaps with an encouraging cousin already having made the journey. Most immigrants’ reasons are a little push and a little pull. I myself have been living in Berlin, Germany, since 2017, primarily pulled by the great quality of life.

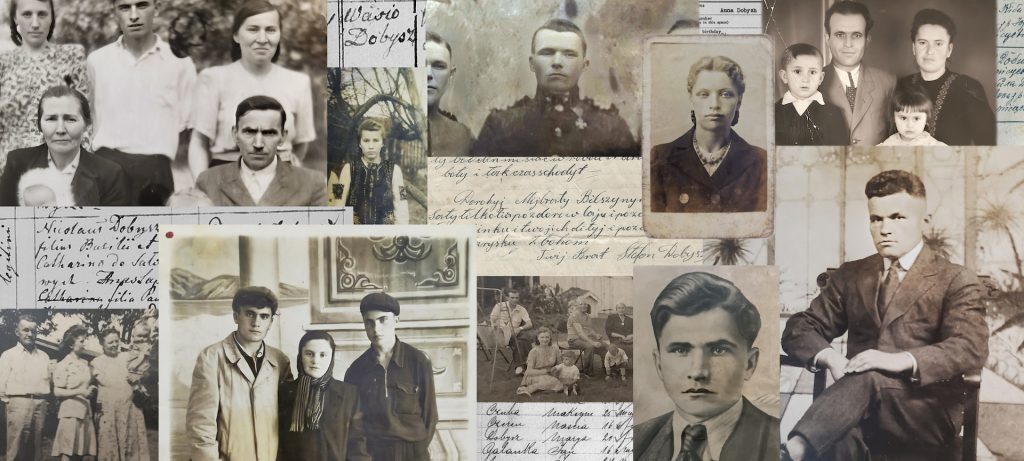

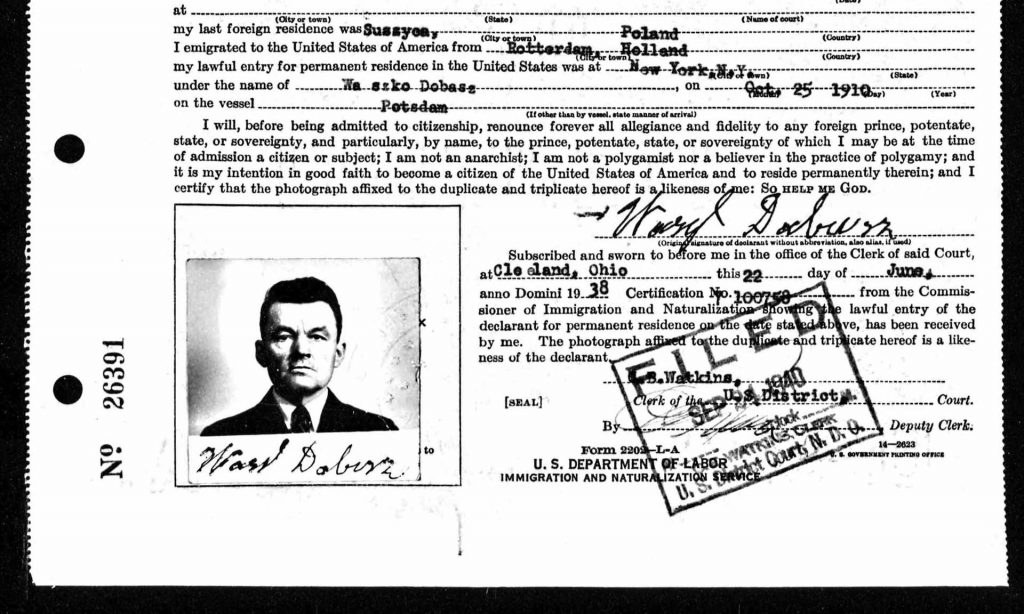

I’m one of 281 million people who currently live in a country other than where they were born. But more than a century before I traversed the Atlantic with my cat in tow, my great-grandfather left his small town in western Ukraine for a better life in Cleveland, Ohio. The area known as Galicia was at various times part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Russia and Poland, and residents struggled through famine after famine. At 18 years old, Wasyl Dobusz left for New York from Bremen in 1910 with $25. He eventually settled in Cleveland, Ohio, and married another Galician immigrant, and had a son, who had three sons, one of whom had me.

Wasyl found work in the steel industry, as many migrants to the Rust Belt did. I never met him before he died in 1973 at age 88, but I grew up with traditions he imported from the old country — pysanky at Easter, halupki and pyrohy for special dinners. My grandfather also became a steelworker, his salary affording him a brand new house for his wife and three sons, and a very comfortable life and bountiful Christmases for me and my brother once we came along in the 1980s.

My grandparents didn’t have any siblings, and my brother and I are the only grandchildren on that side of my family. But last fall a woman named Elena reached out to me on Facebook.

“Sorry to bother you, I’m in the middle of some genealogy research now,” she wrote. Her grandmother’s sister had emigrated from Ukraine to Ohio because of an uncle who already lived there. Did I possibly know anyone named Wasyl Dobush who was born around 1885?

I was shocked but immediately wrote back that, yes, that was my great-grandfather. Elena determined that we shared great-great-grandparents, Mikhail Dobysz and Anna Sawchak, who married in 1883 in Velyka Sushytsya. This made us third cousins. She was able to find Wasyl’s birth record written in Latin in a local metric book in Sambir in Lviv Oblast in no time at all.

Elena herself didn’t grow up in Ukraine — her grandmother’s family and tens of thousands of others from the area were pushed east by the Soviet government to the Ural Region after World War II. Some of her relatives moved back to Ukraine in the 1960s, but Elena grew up in Chelyabinsk in central Russia and now works at a bank in Thailand.

Elena created a Facebook group where she keeps adding more cousins as she locates them, and those cousins are sharing documents that have been stashed away. We recently uncovered some letters between Wasyl and his siblings in Ukraine, and Elena transcribed and translated them to share.

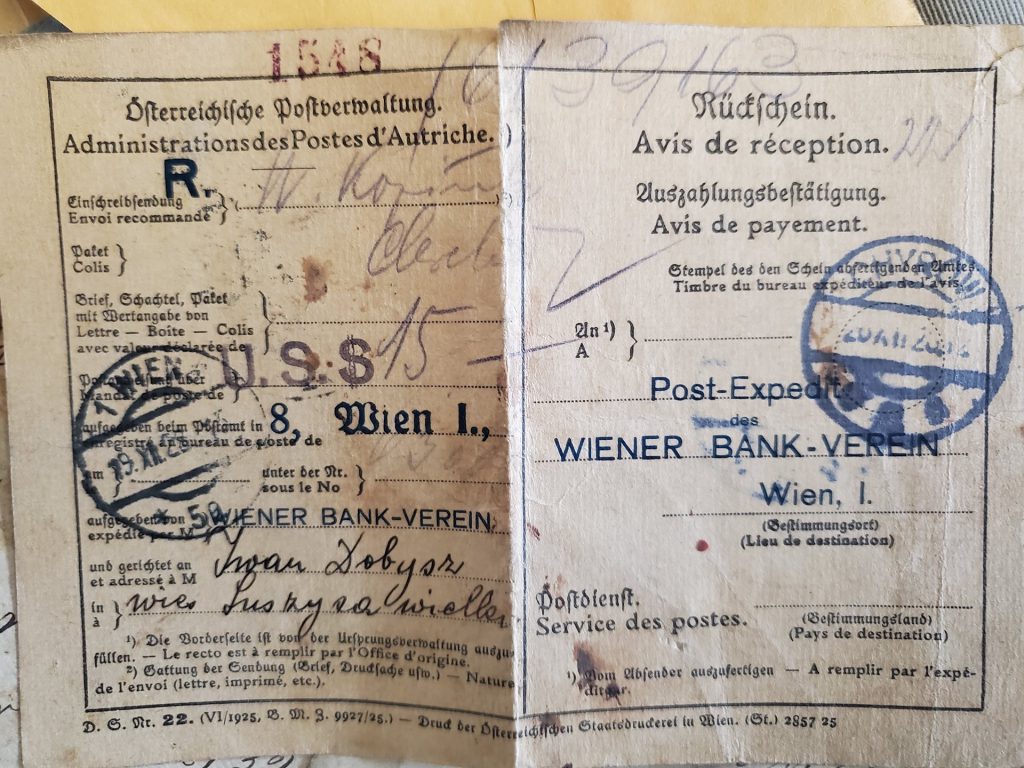

Those who stayed behind told of hard times on the farm and asked Wasyl if he could send leather for boots. In 1924, his brother Nicholas wrote to thank him for the $5 Wasyl had mailed him in Austria, where he had been working. Wasyl sent him another $10 later that year, as Nicholas was still stuck near Vienna without a passport.

With his steelworker’s salary, which was about $30 a week at the time, Wasyl was able to support his wife and son in Ohio as well as help his parents and siblings back home. My uncle recently found receipts for many of these remittances, scraps of yellowed paper inscribed with fountain ink. Wasyl sent $10 to his father in 1924, and $40 in 1925, and then $25 to his brother Ivan in 1926, $15 in 1928, and $25 in 1929, before the Great Depression began later that year. Correspondence seemed to drop off once he wasn’t able to send as much money.

It’s impossible to know exactly how his family used the dollars Wasyl sent to Sushytsya. But we do know that, almost a century later, the descendants of the six children of Mikhail Dobysz and Anna Sawchak are thriving around the world.

And that’s the power of a paycheck. In this first issue of the ADP ReThink Quarterly, we’re exploring the paycheck as a lifeline, with stories of how remittances are sustaining families and changing lives around the world. I hope you’ll go on this journey with us, and you can keep up with everything ReThink by signing up for our newsletter.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.