Technical advances have led to fears about job security for centuries.

And yet, when a machine replaces one job, it might create another. Indeed, there’s plenty of evidence that automation helps create jobs, both upstream and downstream, to mostly offset the losses that it causes.

The Future of Jobs report from the World Economic Forum (WEF) predicts that about 83 million old jobs will vanish over the next five years, and about 69 million jobs will be created.

The problem is that the millions of people who are projected to lose their jobs may not be the same people who snap up the new jobs. This is mostly because they don’t have the required skill sets to move into a newer version of their job or transition to a different career.

While fears of a “job apocalypse” are clearly overblown, newer technologies like generative AI will definitely “affect how people work and result in significant job displacement,” says Thomas Kochan, Professor of Management and Co-Director of the MIT Sloan Institute of Work and Employment Research.

The solution to this is reskilling when new technologies are introduced and constant up-skilling to remain relevant. “Training has to be done on a continuous basis and start well before new technologies are introduced into a workplace,” Kochan says.

The disruption to come

The numbers are stark. The WEF report — which looked at 803 companies employing 11.3 million workers across 45 economies — lays out the scope of the challenge.

The WEF estimates that 44% of workers’ core skills are expected to change in the next five years, requiring reskilling or upskilling. And while six in 10 workers will require retraining before 2027, only half of them have access to adequate training opportunities today.

Ling Li, a Decision Sciences professor at Old Dominion University in Virginia, has written extensively about problems in future-proofing the West’s workforce.

“Skill gaps are inevitably increasing unless today’s workers, who are at most risk of losing their jobs, learn new technology and take the opportunity to acquire the skills required for future employment,” Li notes. “While certain higher-skilled workers have seen their pay increase, many others have seen median wages stagnate, with their job security becoming more precarious.”

The reality of the reskilling problem is more complicated than those simple statistics, because not all jobs are being disrupted in the same way. Affected employees fall into one of three categories, each of which requires a separate reskilling or upskilling strategy:

Totally redundant

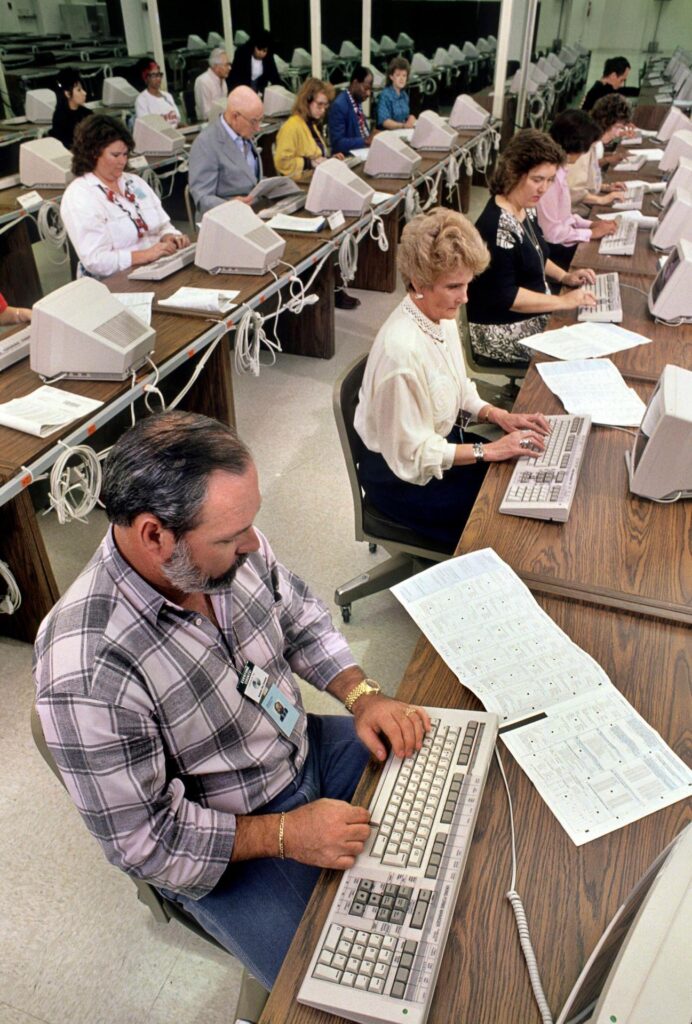

At the bottom of the food chain are the jobs that are completely disrupted or destroyed. These jobs can’t evolve with automation and are made completely redundant by technology.

For example, the Covid-19 pandemic accelerated the shift to electronic toll booths across the United States — from California to Pennsylvania. The process eliminated thousands of toll workers, many of whom were replaced by automated e-ticket collectors.

Changed ways of working

And then there are jobs where automated tools, machines and new software are changing the nature of work. For instance, Walmart store staff are learning how to work alongside cleaning and inventory robots by figuring out how to manage, operate and integrate them into their workflow.

Content creators are dabbling in generative AI tools. Doctors are using predictive software and augmented reality tools to diagnose and treat cancer. And in financial institutions, new software is being used in everything from personalized customer service to fraud detection.

Total retraining

In the final pool of jobs, sweeping shifts in policy and priorities upend an industry, but the workforce can be retrained to do a different job.

The quest for net-zero carbon emissions is a good example of this challenge. Many European countries have banned or are planning to restrict the use of oil and natural gas heaters. They will be replaced by green alternatives like heat pumps. Thousands of heat engineers, workers and repairmen need to be reskilled to accommodate this clean energy transition. McKinsey estimates that about 80 million people will need to be retrained across cleantech sectors.

The challenges ahead

The guide to reskilling an organization’s employees is simple on paper, but often difficult to execute. It starts, as most things do, with data. Companies usually don’t have a clear view of their employee’s existing talents, learning capacity and how exactly they want to implement new technology.

“Management or HR may have ideas on identifying what needs or warrants upskilling. But are they what are really needed?” asks Susan Vroman, a leadership development specialist and lecturer at Bentley University in Massachusetts.

“Some say the biggest problem is finding the budget or the resources to do the upskilling. But I’d say determining what will make the biggest impact is the bigger challenge,” she says. “Triangulating multiple sources of data to identify these opportunities takes time, and many organizations just don’t want to do that. They want to flip a switch or hire a consultant and make it happen.”

Reskilling strategies are the easiest to pull off when a company’s automation goals include bringing its employees along for the journey.

Over the last year, American bank Capital One has been testing AI tools. The company wants to be able to monitor customer transactions and offer them personalized advice. Instead of buying a software solution, the company started upskilling its current engineers, putting them through a six-month training course on AI and machine learning.

At Royal Bank of Canada, the company’s management has asked workers across verticals to start becoming familiar with AI tools. This includes everyone from customers service reps — who the company hopes will be able to build case summaries of clients based on past interactions — to investment managers.

The second hurdle is often money. Even when the economy is strong, companies are reluctant to invest the funds needed to retrain or upskill their employees. Hiring new employees or contract workers is sometimes the easy way out.

ADP’s People at Work 2023: A Global Workforce View report found that 87% of workers reported feeling optimistic about the future, and 68% say their employer invests in the skills they need to advance their careers.

In 2021, online retail giant Amazon pledged $1.2 billion towards upskilling and reskilling efforts. The effort covers degree programs, on-the-job training and certification courses.

Two of the most popular non-college education programs among Amazon employees were foundational English as a Second Language classes and truck-driving certifications. This indicates that while specific reskilling strategies are useful, an integral part of future-proofing involves encouraging entry-level and frontline workers the chance to move up the ladder.

Beyond this, Amazon’s most serious homegrown reskilling and upskilling initiatives are ones that revolve around its business interests. Its AWS “Grow Our Own Talent” initiative trains low-level technical staff for roles at the server centers that underpin its web services division. While the company acknowledges its upskilling efforts will help its workers get a better job anywhere, there is little doubt that its in-house programs are aimed at roles that are specifically aligned to the company’s future.

Preparing for the future

Governments are also playing an important role in upskilling and reskilling workforces in many parts of the world. The WEF report found that 45% of businesses consider funding for skills training as the most effective governmental intervention for connecting talent to employment.

Government funding has the additional benefit of ensuring that reskilling and training programs place the employee at the heart of the process.

“Leaving training decisions solely to management has failed to provide sufficient training to meet the needs of the workforce or the economy. So, tax incentives will not do the job. Joint training programs for current employees and joint apprenticeship programs for new hires are better models,” says MIT’s Kochan.

In Singapore, the government’s SkillsFuture program reimburses each citizen up to 500 Singaporean dollars ($362) for an approved reskilling course. This incentivizes workers to continuously learn.

In Sweden, most employers voluntarily pay into “job security councils,” private funds that help workers with retraining if they get laid off. A similar system exists in France, where employers are required to finance the vocational training system.

In the 1980s, reeling from a major worker’s strike, General Motors spent billions in trying to replace its workforce with robots, in an effort to catch up to Toyota’s far more efficient production system. But its global market share only went up a single percentage point.

Later, when the company teamed up with Toyota on a joint venture, GM grew to understand the Japanese firm’s way of allowing workers to give “wisdom to the machines” — discovering a way for human employees to work in tandem with automated processes and make them better. And that is perhaps what successful training, reskilling and upskilling is all about.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.