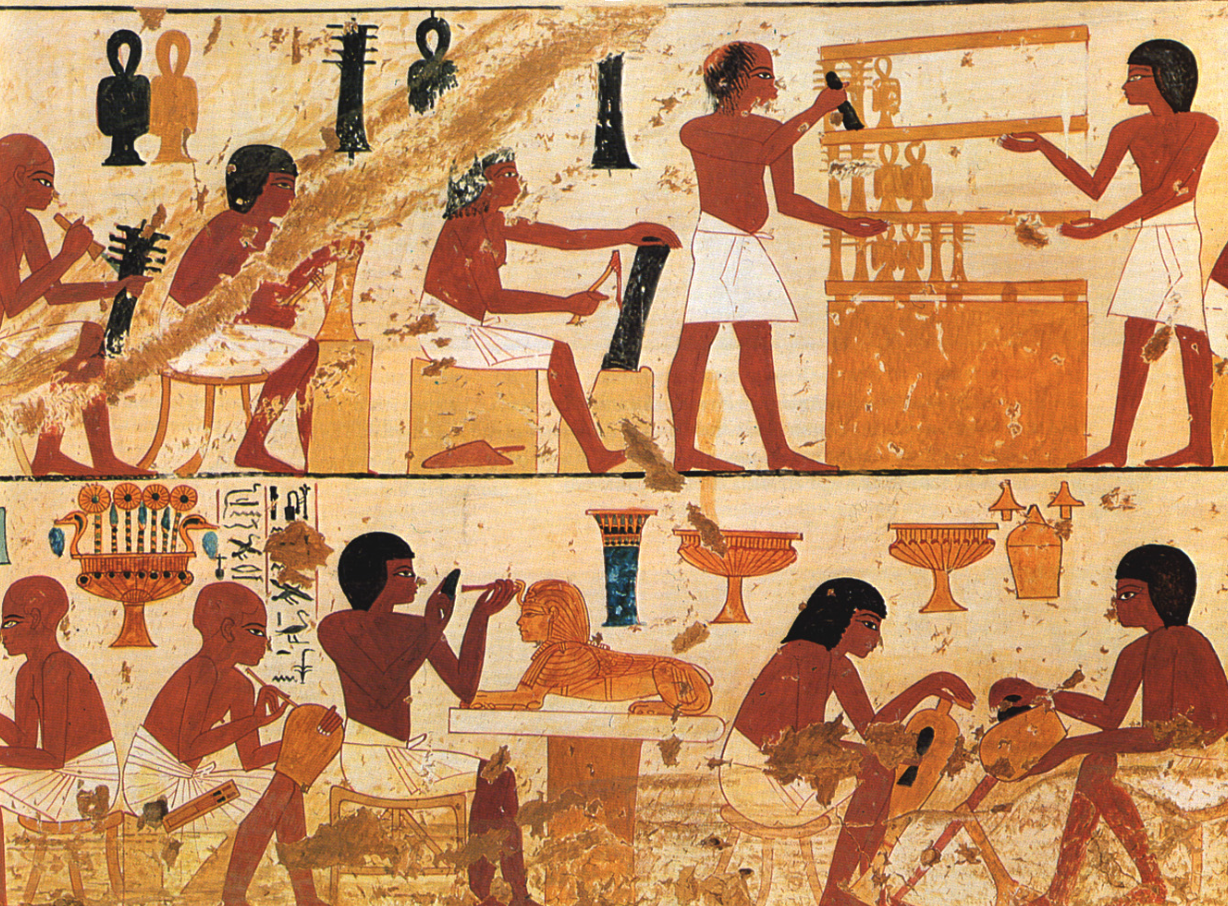

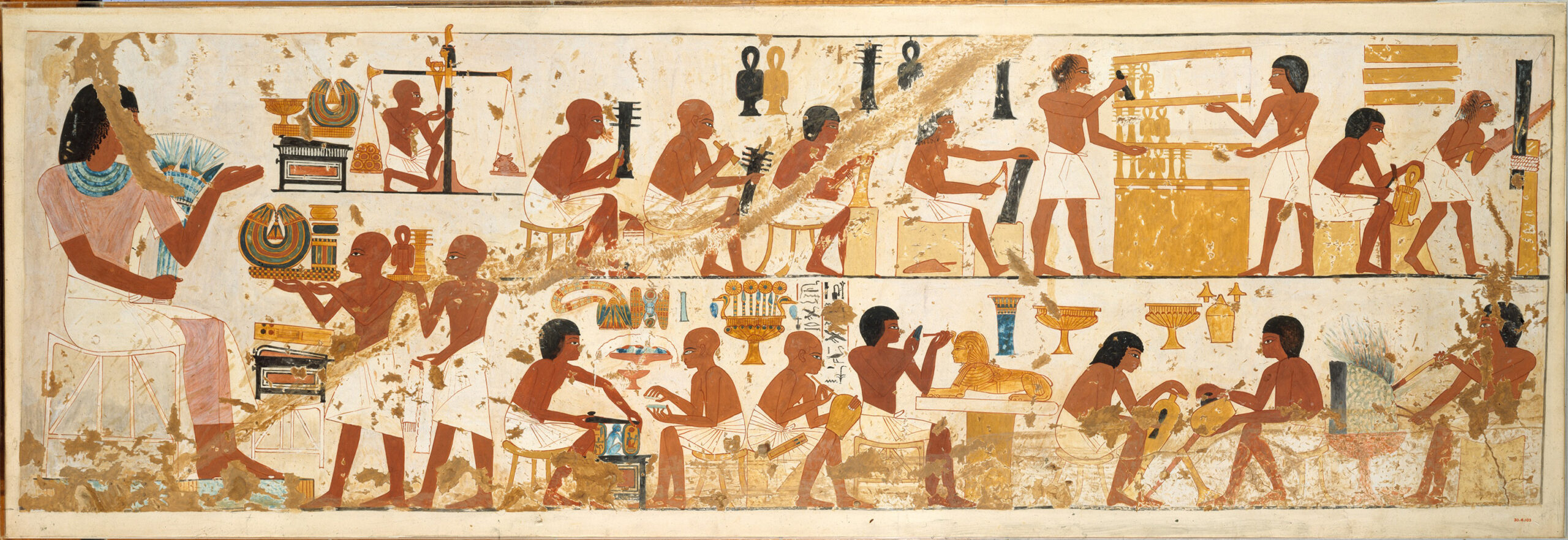

Workers collectively withholding their labor has long been one of the most effective tactics for getting their demands met — maybe longer than you think. In fact, the earliest known labor strike occurred in 1157 BCE in Egypt during the reign of Ramses III.

The tomb-builders in Thebes were surprised when the monthly payment for their work — they were compensated in food rations — failed to arrive. Local officials were busy with preparations for a celebration of Ramses III’s 30th year as king of Egypt. They appeased the workers by distributing some grain, but when the wages repeatedly failed to arrive on time, the tomb-builders walked off the job.

Details of the strike are recorded in the “Judicial Papyrus of Turin” held at the Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy. In the entry for day 12 of the second month of winter, a scribe recorded that the workers met with representatives of the Pharaoh and said, “The prospect of hunger and thirst has driven us to this; there is no clothing, there is no ointment, there is no fish, there are no vegetables. Send to Pharaoh, our good lord, about it, and send to the vizier, our superior, that we may be supplied with provisions.”

Ancient Egyptians believed that a critical element of their society was harmony or balance in communities and in the world generally, which they called ma’at. Furthermore, they believed it was the king’s responsibility to maintain this harmony throughout the land. Responsible for constructing the royal tombs, these builders considered themselves the “essential workers” of their day, and the failure to pay their wages on time was a serious violation of ma’at.

In a display of solidarity, the workers put down their tools and marched toward the city, chanting, “We are hungry!” They protested outside of important buildings and eventually forced their way into the city’s granary and demanded payment. When the next month’s payment arrived late, they blocked roads of the Valley of the Kings.

The delayed payments and work stoppages continued for three years until higher officials apparently improved the system for paying the workers. But according to writer and scholar Joshua Mark, by making demands that would restore harmony or ma’at to Egypt, which was the Pharaoh’s duty, the workers had “been forced to assume the responsibilities of the king.”

The rulers and philosophers of the ancient world were certainly thinking about the potentially ‘disruptive’ role of workers in their societies. In “The Republic,” written around 375 BCE, Plato considers the composition of a society and explores aspects of the city-state and justice. In Book VIII of this Socratic dialogue, Plato discusses forms of government and the role that groups within society play in those governments. One modern scholar analyzing Book VIII of “The Republic” notes that in Plato’s version of an ideal society, there are three classes, including one composed of “laborers and the artisans, and they make up the mass of the people.” In Plato’s understanding of workers’ collective power, when the workers “meet, they are omnipotent, but they cannot be brought together unless they are attracted by a little honey; and the rich are made to supply the honey, of which the demagogues keep the greater part themselves, giving a taste only to the mob.” In other words, Plato saw the potential of the laboring class to have total power over the other two classes, but because workers were only ever brought together by demagogues, he believed they would simply be manipulated for the personal gain of a few.

Ancient contracts and norms

Perhaps surprisingly, some laborers of the ancient world entered into written contracts, many of which still survive. George Aaron Barton, professor of Semitic Languages at the University of Pennsylvania in the early 1900s, translated some of the 30,000 clay tablets stored in the university’s museum.

Sometimes parents entered into labor agreements on behalf of their children. In ancient Mesopotamia, parents signed many contracts to be paid for their child’s labor. In 2200 BCE, one mother signed a contract for her son, Marduk-nasir, to work for a man named Mar-sippar. In Egypt, around 20 BCE, when it was part of the Roman Empire, a farmer named Harthotes in Theadelpheia signed a contract for his daughter to go to the village of Philagris to work in an imperial oil mill for two years. He later renewed the contract for another two years.

Given that so many of these ancient contracts were signed by guardians for their children, it stands to reason that entrusting their sons and daughters to distant employers required an additional layer of security: a written contract. Some of these contracts were literally written in stone.

In the ancient world, labor rights were often based on widely held norms, which sometimes were also sacred rules. Scholars date the Book of Shemot in the Torah, called the Book of Exodus in the Christian Bible’s Old Testament, to the 500s BCE. It is believed to be a compilation of written and oral traditions from the previous four centuries. It tells the story of Moses receiving the Ten Commandments from God. The fourth commandment states: “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor, and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God.” This commandment effectively limited the workweek for many societies up through the present. It not only limited it for all heads of households but also for children and servants by adding: “You shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter, your male servant, or your female servant, or your livestock, or the sojourner who is within your gates.”

Resistance in the Roman Empire

In ancient Rome, there were two classes of citizens–patricians and plebes, as well as a third class, slaves, who were not citizens. One history of early Rome, written by Titus Livius, offers accounts of plebeian protests and resistance, including what became known as the 1st Secession.

While plebes did not serve in Rome’s legislatures, they did serve in the army, and at that time, Roman society was regularly under military threat. In 494 BCE, while patrician legislators were preparing to raise another army, plebes began holding nighttime gatherings to discuss their rights. According to Livius, the senators considered forgiving some plebeian debts to entice them into the military. But instead, the lawmakers named a dictator who forced the plebes into service and won a great victory. However, when they attempted to fight a second war with the same army, the plebes left the city en masse, constituting the 1st Secession.

According to Chris Salatin, an expert on the Roman Empire, Livius’s account likely contains several important inaccuracies, because he was writing about events that had happened centuries earlier. Nevertheless, the goal of the secession seems clear: the plebes left the city for a fortified location three miles away and forced the patricians to run the city without them. The 1st Secession ended when the patricians agreed to form the Tribunes of the Plebes and a Council of the Plebes, which did not give the working class any legislative power but did give them a voice in the governing of Rome.

In a 1963 article titled “Strikes in the Roman Empire,” scholar Ramsey McMullen noted that when “strike” is broadly defined as a “refusal to work,” it is possible to find many instances of strikes. In fact, at one point the empire’s craft guilds were outlawed for fear they might foment riots or simply stop working and weaken the cities. However, some workers were considered so “essential to the public” that their associations were tolerated by the authorities. They included builders, shippers and bakers.

One Roman strike took place in the city of Ephesus, the ruins of which are located in present-day Turkey. Ephesus was famous for being home to the Temple of Artemus, built around 550 BCE and one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. By 200 CE, Ephesus was part of the Roman Empire. Around that year, the bakers of Ephesus created a riot in the market square, likely protesting their working conditions and the price of bread. Details of the event are quite limited because our only account of their revolt comes from an incomplete edict etched in a broken piece of marble and held at the Museum of Istanbul. At the time, market supervisors set the price of bread, which apparently undercut the bakers’ ability to earn a living. Furthermore, disruptions in the grain supply sometimes led to bakers’ protests. It may have been that both circumstances occurred at once, leading the bakers to riot against imperial control.

In the riot’s aftermath, a Roman official issued the edict, noting that the bakers who had caused the recent “disorder” had already been arrested and tried. In case it was not clear, the official added that the bakers must not be so “bold” again, and that they must comply with “official commands by providing the necessary labor” to play their essential role in the city.

These strikes and revolts of the ancient world are very different from labor strikes we know today. Even the guilds of the Roman Empire would not be recognizable as workers’ organizations — they might look more like a religious sect combined with an industry association. Work stoppages occurred when there was a breakdown in the social and economic systems of the society.

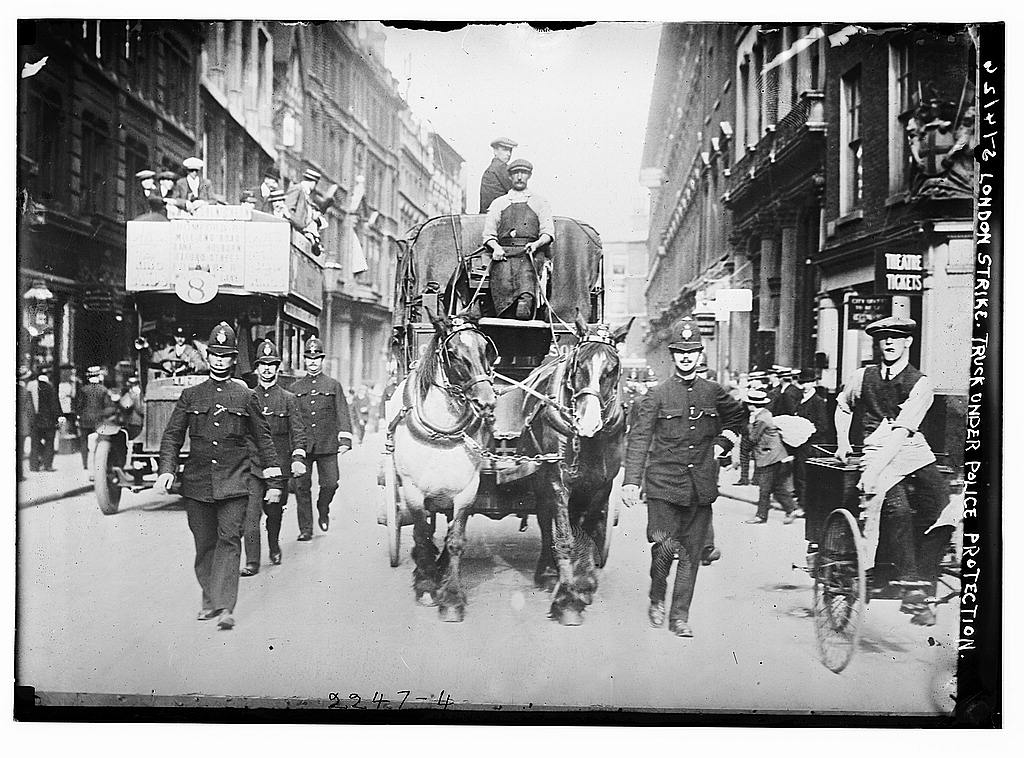

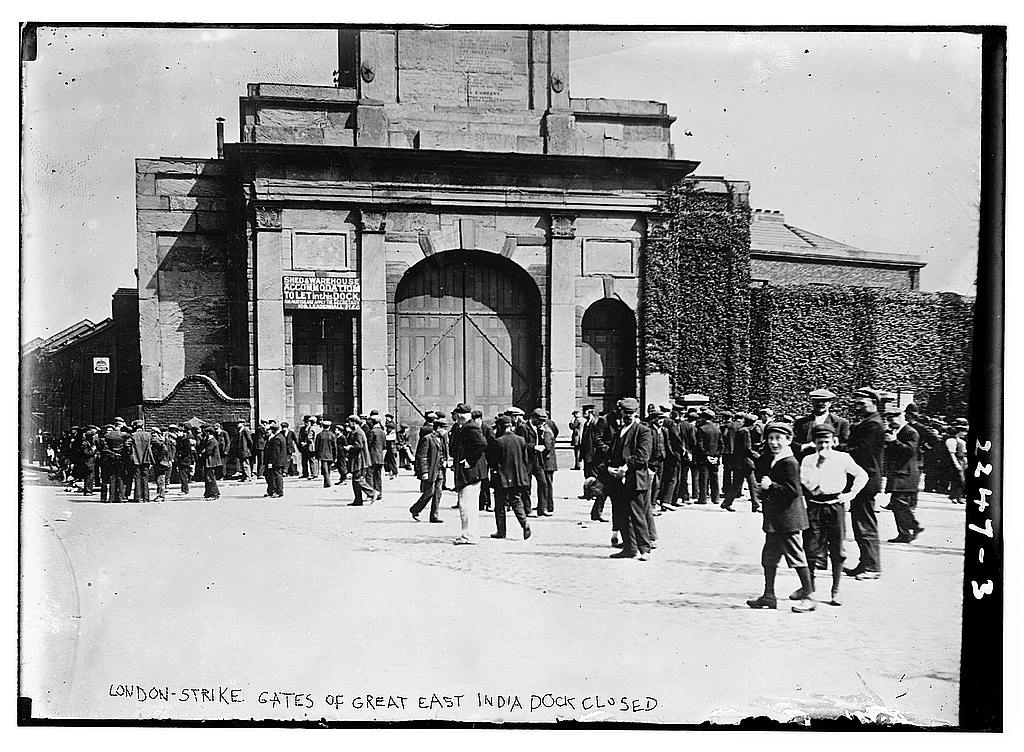

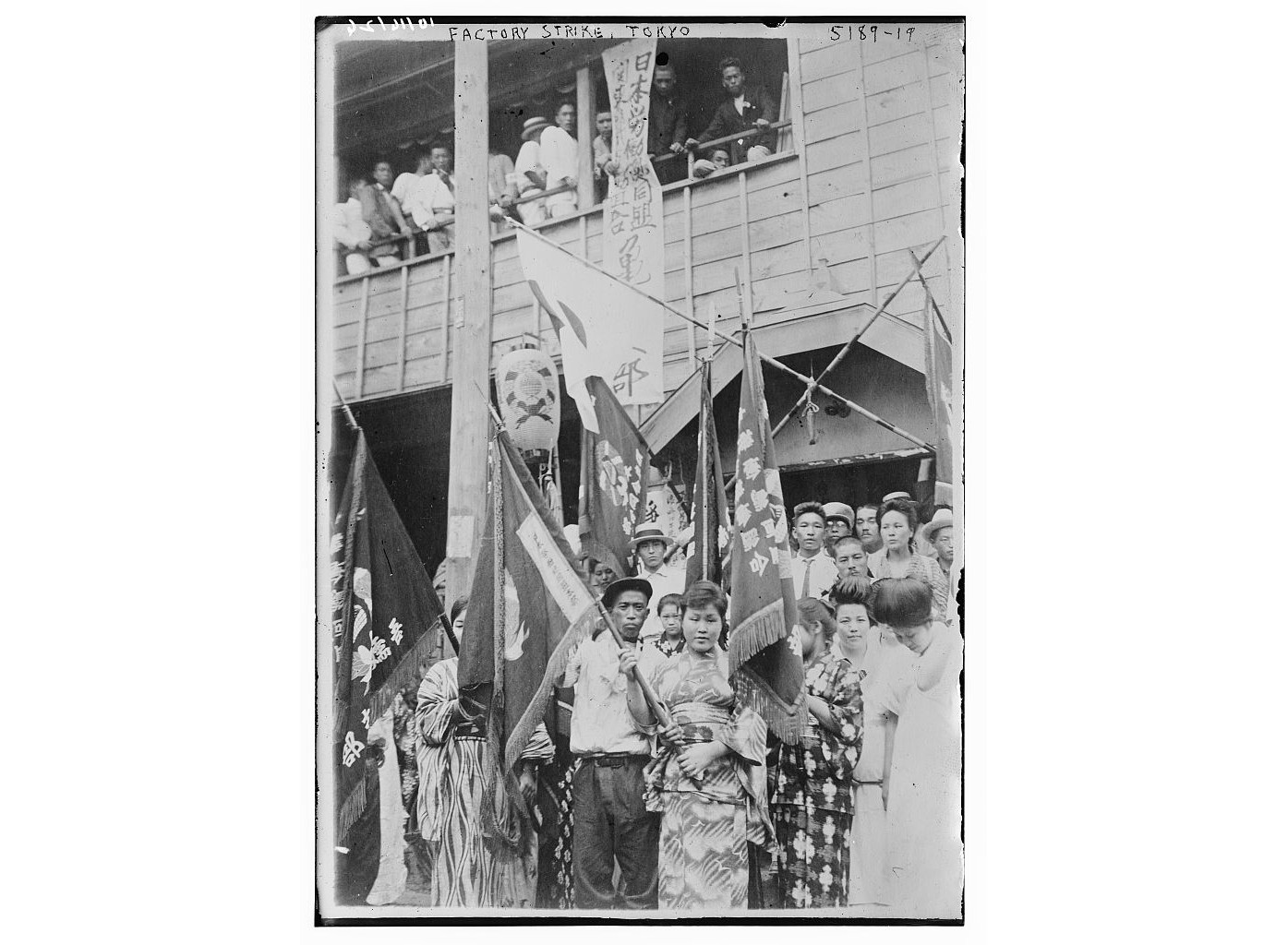

It would not be until the industrialization of the last couple centuries that workers would walk off the job to form picket lines and make demands on their employers in ways we would recognize today. This only came with the development of large numbers of people working the same jobs — a concept that did not exist in the ancient world — and having widely recognizable rights as employees.

Yet, there are still parallels to those ancient events where people came together to make demands for decent working conditions and a living wage.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.