All money hinges on regional cooperation. Today, we take for granted that a coin or bill we receive in one city will be worth the same amount in the next town or province.

As modern states formed, monarchs had already implemented ways for people to redeem their taxes through gold and silver coins. Over time they eventually gave way to fiat currency, which is not backed by a commodity like gold or silver.

In some very rare cases, multiple states and territories have banded together to create a more powerful communal currency. Financial endeavors like these offer greater stability but require much fiscal discipline. Our tale of economic integration, political cooperation and the power of a single means of payment starts with the birth of the United States.

American finance

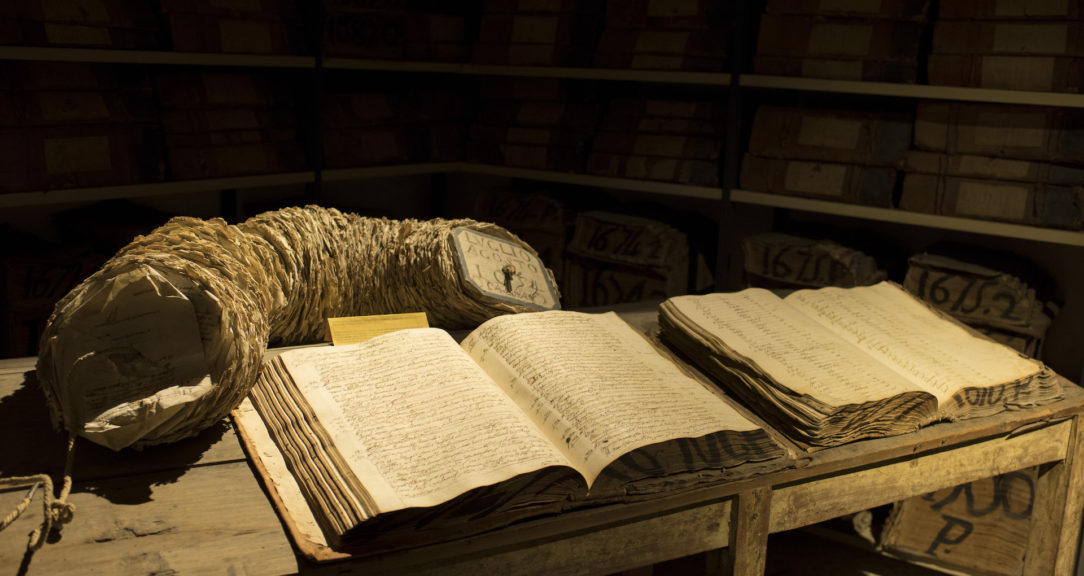

In the late 17th century, many people worked in self-sufficient agriculture. Trade was mostly local, and banking was still in its infancy. People making market transactions settled up with available gold and silver coins, or via barter.

An insufficient supply of gold and silver was a consistent problem for colonists in New England. They wanted to finance their growing economies and increase international trade between Boston, Philadelphia and New York with Portugal and the Caribbean. Colonial governments also faced debts, resulting from England’s war with France in Canada.

Colonial governments, starting with Massachusetts in 1690, began to issue a variety of payment forms that served as paper currency, including bills of credit and treasury notes, but not all of it was within reach of ordinary folks. They also issued some coins, but these were relatively rare in New England.

The British Parliament’s Currency Acts restricted the New England colonies in their attempts to issue or use paper currency. This effort to tighten control made it difficult for the colonies to finance their economies and conduct trade and contributed to the growing tensions between the colonies and Great Britain.

During the American Revolution (1775-1783), the need for a unified means of payment became more apparent. The Founding Fathers had already recognized the importance of a stable national currency and incorporated it into the U.S. Constitution, which gave Congress the power to “coin Money, regulate the Value thereof.” The Continental Congress issued Continental Currency, primarily as a means to finance the war. The Continental Currency was fiat currency, meaning that it was not backed by gold or silver, and it became worthless by the end of the war.

But the need for a currency that could unify the 13 United States and promote economic stability remained. In 1792, as part of reforms introduced by Alexander Hamilton, secretary of the Treasury under President George Washington, the federal government created the modern U.S. Mint, which introduced the dollar, a common currency for the growing nation.

In the early years, the U.S. followed a bimetallic system, with both gold and silver coins in circulation. This bimetallism aimed to provide stability in the monetary system but faced challenges as the relative value of gold and silver fluctuated in international markets.

During the 19th century, local banks were in charge of issuing paper money. This period of “free banking” lasted until 1913, when the Federal Reserve System was established. The central bank of the United States introduced Federal Reserve Notes — U.S. paper dollars backed by gold.

The European experiment

At the end of World War II, the might of the U.S. dollar led other countries to consider the advantages of adopting a common currency. The U.S. experience showed that increased trade can lead to greater economic interdependence, and the elimination of exchange rates reduced transaction costs.

The formation of a unified currency area is understandably complex but makes sense when certain criteria are present. Potential members should be close geographically, with a high degree of trade and similar economic structures.

In Europe, a continent historically divided by competing national currencies, some countries found a desire for unity and peace that led to what would become the European Union. Born from a set of agreements to control materials critical for war, such as carbon and steel, this eventually grew to a common trading area and monetary union.

A first step towards a single currency was a monetary arrangement negotiated by nine countries between December 1971 and April 1972: France, West Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Denmark. They agreed to a maximum 4.5% fluctuation between their currencies, called “the snake in the tunnel” for its shape on maps. Central banks would intervene if market exchange rates approached these limits. They also agreed to create a unit of account, whose value was defined in relation to gold as a replacement for the dollar.

The arrangement was short-lived. Currencies came under speculative attack, and members were unable to keep to the narrow margins imposed by the system. The pound sterling, the Irish punt and the Danish crown were then allowed to float freely within a couple of months. Political disagreements between France and Germany decapitated the snake in July 1972.

But the Europeans tried again, establishing the European Monetary System in 1979, aiming to stabilize exchange rates between participating currencies in preparation for a monetary union. The European Currency Unit, a precursor to the euro, was used for accounting purposes and acted as a reference point for the exchange rates of European currencies.

The real push for the euro came with the Maastricht Treaty of 1992, which included a roadmap for the European Economic and Monetary Union, with a single currency being one of its key components.The European Central Bank was established in 1998, with a mandate for setting monetary policy and ensuring the stability of the currency.

On 1 January 1999, the euro replaced the European Currency Unit as an accounting currency. And then on 1 January 2002, euro banknotes and coins were released to the public and the euro became the official currency for 12 countries.

The euro has continued to expand and is now used by 20 of the 27 European Union member states, plus Andorra, Kosovo, Monaco, Montenegro, San Marino and the Vatican. The European debt crisis of 2009 and ongoing debates about fiscal and monetary coordination among Eurozone members have tested the resilience of the currency union.

But the success of the euro reflects a long and complex process of European integration, marked by the desire to collaborate in building common institutions, promote economic stability and peace among nations. While the euro has faced challenges, it stands as a symbol of the potential for regional cooperation and monetary union in a multi-currency world.

Caribbean connections and African unity

Other monetary union successes can be found in the smaller economies of the Caribbean and across French-speaking African countries.

Between 1946 and 1965, Caribbean islands formerly under British rule participated in different political and economic experiments to create a shared currency. Some of these initiatives were promoted by the United Kingdom, like the British West Indies dollar in British Guiana and the Eastern Caribbean, introduced in 1949. In the West Indian Currency Conference of 1946, Barbados, British Guiana, the Leeward Islands, Trinidad and Tobago and the Windward Islands agreed to establish a unified decimal currency system based on a West Indian dollar.

The East Caribbean Dollar (XCD), a successor to the British West Indies dollar, was introduced in 1965 and has sustained. There are eight current members of this currency union, including Antigua and Barbuda, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, plus Anguilla and Montserrat, both British Overseas Territories. The East Caribbean dollar, pegged to the U.S. dollar at a rate of XCD 2.70 to $1 since 1976, has allowed for easier commerce, trade, and economic stability among these tropical lands.

Across the Atlantic Ocean, the West African and Central African CFA francs were created through an agreement with their former colonial power, France. Both CFA francs are pegged to the euro at 655.957 per €1.

The West African franc was introduced to the French colonies in West Africa in 1945. At present the currency is currently used by eight currencies: Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo, which have a combined population of more than 140 million.

The Central African franc is of equal value to the West African CFA franc, and is in circulation in six countries: Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea and Gabon, the total population of which is about 64 million.

The CFA francs have come under scrutiny in the past decade — supporters say the currency’s stability has helped spur growth and limited inflation in the 14 countries using them, while critics say the CFA franc is a remnant of colonialism that limits autonomy. But these currencies have become a symbol of post-independence economic cooperation, promoting trade among these African nations.

The African Union has been a proponent of one common currency for the entire continent. The Abuja Treaty, signed in 1991 by 54 African countries, calls for an African Central Bank to implement a unifying African currency by 2028. It’s a big goal, but many intermediate steps have already been completed: The African Continental Free Trade Area went into effect in 2021, followed by the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) in 2022.

The regional trade bloc in South America, known as MercoSur, has considered the idea of a common currency. This could be attractive for countries that have experienced serious inflation, but the initiative has lacked the political determination and investment to create a common institution as in Europe.

The appeal of cross-regional currencies is clear: These currencies can provide stability, foster growth, and pave the way for stronger political and economic integration. Common currencies don’t guarantee any of these results, but every step provides some more progress towards a more perfect union.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.