In 2020, about 281 million people lived in a country other than the one in which they were born. If international migrants formed a single country, it would be the fourth-largest in the world. The number of migrants has been rising steadily for years, but it dropped for the first time in decades during the pandemic, as some workers returned home by choice or by necessity.

Accordingly, remittances — money sent home by immigrants out of their own paychecks — were also predicted to drop in 2020 after years of growth. In the pandemic, “migrants have gotten the worst end of things,” says Melissa Siegel, a professor of migration studies at Maastricht University. “Migrants are often in sectors that are the hardest hit by a recession. And on top of that, a lot of migrant workers have been hard hit by the virus itself.”

Worldwide flows of money in 2019

Global remittances topped $717 billion in 2019, a record high. But the World Bank estimated the pandemic and recession would cut those flows by about 7% in 2020 and again by 7% by the end of 2021, with low-income countries in South Asia taking the biggest hit.

The pandemic effect

And yet, some countries are reporting record levels of remittances in 2020. Kenya reported total inflows of $3.1 billion, up 11% over the previous year. Mexico also recorded a record $40.6 billion in remittances in 2020, an increase of more than 11% from 2019.

As final numbers for 2020 come in, it’s difficult to say whether remittances are really on the rise or we’ve just gotten better at recording them. There’s also often a spike in money transfers during crises. “Remittances can increase in times of crisis because people might use formal channels, but also migrants might be preparing for their own return, transferring more savings home,” Siegel says.

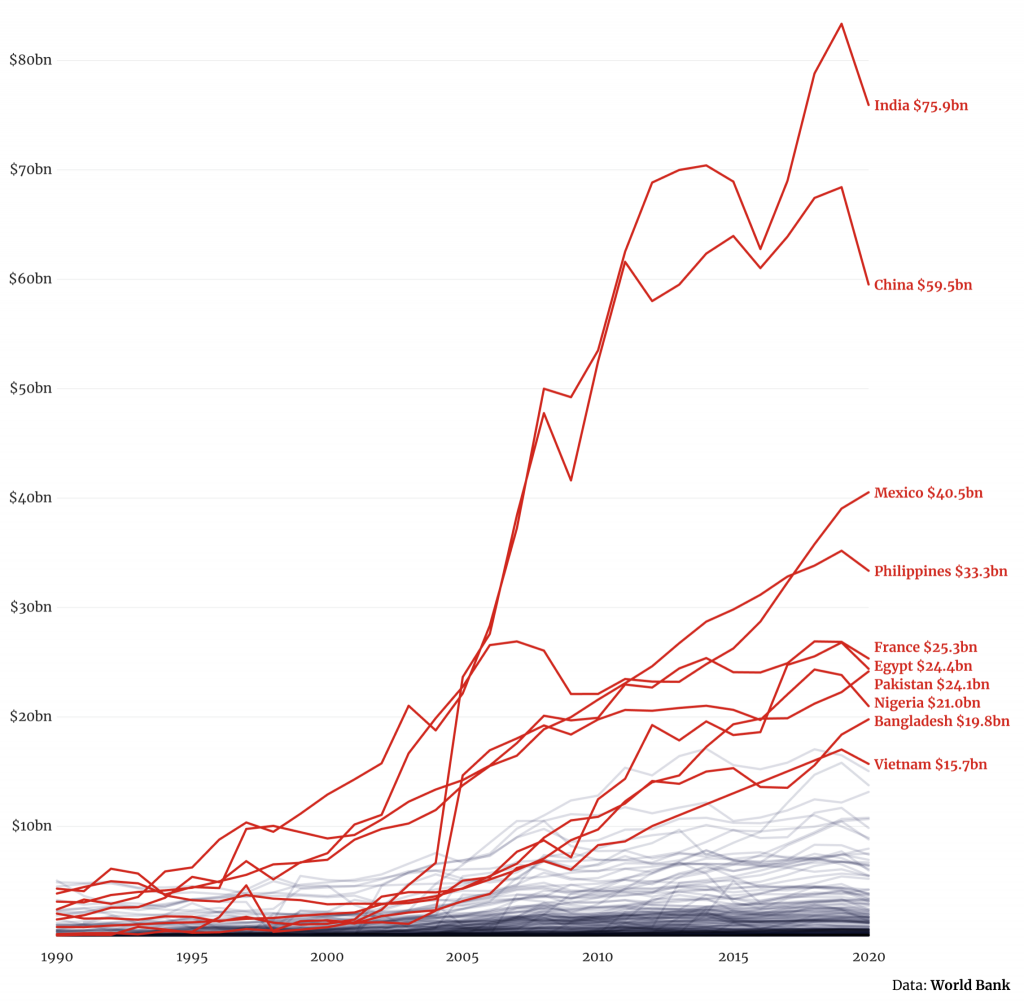

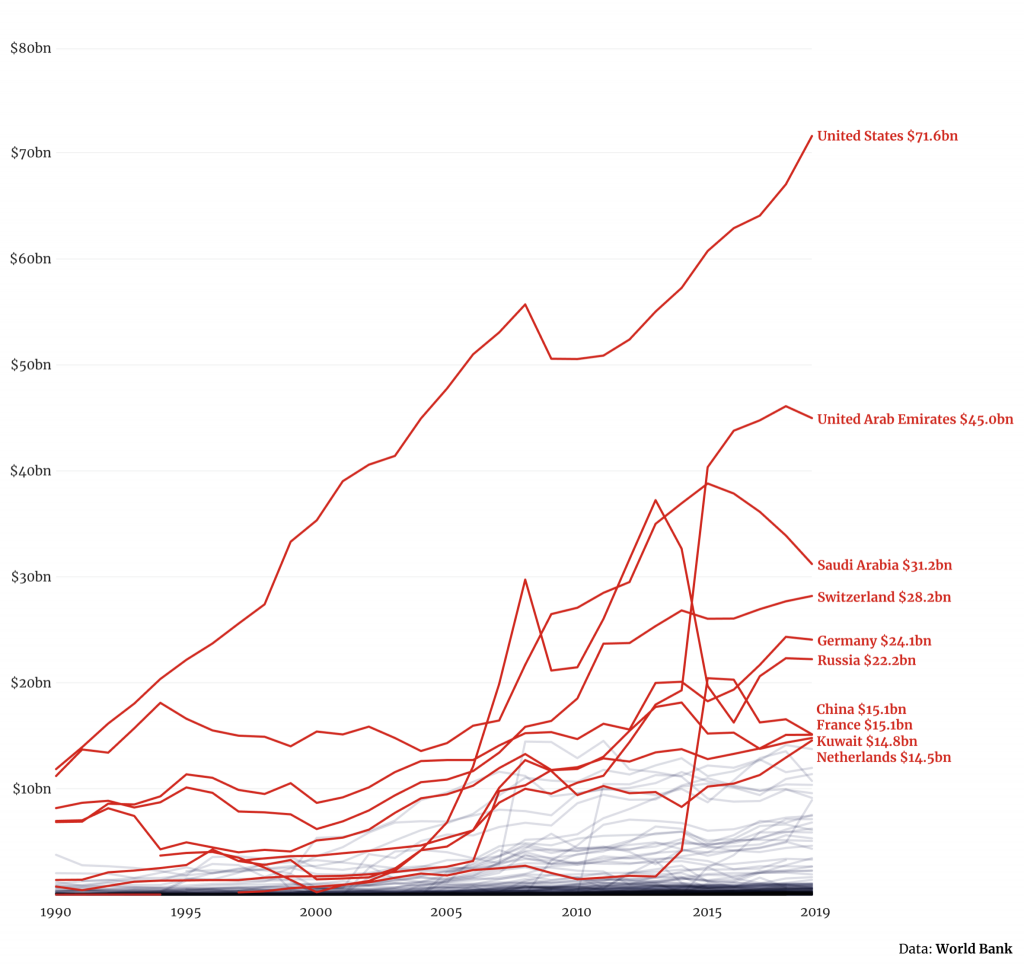

The biggest players in remittances

The changes in flows of remittances reflect the geopolitical changes in the world. The United States has been the top sender of remittances for decades, but the United Arab Emirates jumped to the No. 2 spot after the financial crisis of 2008. India and China have topped the list of biggest receivers since around 2005.

Top remittance receivers

Top remittance senders

Remittances are often vitally important to recipient countries, and in total have outpaced international development aid since the 1990s. In Haiti, Lebanon and South Sudan, for example, remittances account for more than one-third of total GDP. Unlike development aid, remittances go straight to the people, funding businesses, paying for schooling and ensuring the survival of entire families in some cases.

“Remittances are much better at targeting those who need them the most,” Siegel says. “They are extremely important for those who stay behind. Remittances reduce the depth and severity of poverty, and can eliminate poverty.”

Remittances are growing far faster than aid

Thanks to mobile banking services, sending money around the world is cheaper, faster and easier than ever before. But the options and their costs vary widely depending on the region. The U.N. wants to get remittance fees down to 3% by 2030. And the average cost to send money to low- and middle-income countries has dropped to 7%, but the cost in Africa remains higher than anywhere else, about 9%.

When it comes down to it, remittances show the power of the paycheck. Paul Vaaler, a professor at the University of Minnesota’s law and business schools, calls remittances essentially “venture capital running from migrants abroad to their extended family and local community recipients back home.” Even small amounts of money can make a big difference.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.