As a professional diver, there are a few things you don’t want to think about before descending into dark waters.

Shark attacks, unsurprisingly, are at the top of that list.

So it was more than a little dampening for Australian commercial diver Kate Pritchard, early on in her career, when one boat operator plunged into the topic.

“We were getting our gear ready when the captain said to me: ‘The only place along this coast that someone’s been taken by a great white was an abalone diver just around this spot,’” Pritchard says. “It was a weird conversation to have with someone before getting in the water. I said to him afterwards, ‘We don’t need to do that again. Next time we’ll talk about it after we get back at the end of the day.’”

Luckily for Pritchard, in the nine years she’s been professionally diving, first as a marine biologist and later as a commercial diver, that mistimed conversation is the closest she’s come to an unwanted encounter with a shark.

With its physical demands, freezing temperatures, challenging visibility and potentially dangerous marine surroundings, a career as a commercial diver certainly isn’t for the faint-hearted.

But despite the risks, a select group of people around the world continue to chase a career in the deep, where every day offers a new chance to put their skills to the test in trying conditions.

In Australia, almost 3,700 people are currently certified to work as commercial divers by the Australian Diver Accreditation Scheme (ADAS), an internationally recognized occupational diving certification program. For comparison, the U.S. counts fewer than 2,700 commercial divers.

The industry

Unlike their recreational colleagues, commercial divers aren’t heading underwater to see the sights. Commercial divers aren’t actually employed to dive, but to undertake work in a submerged environment.

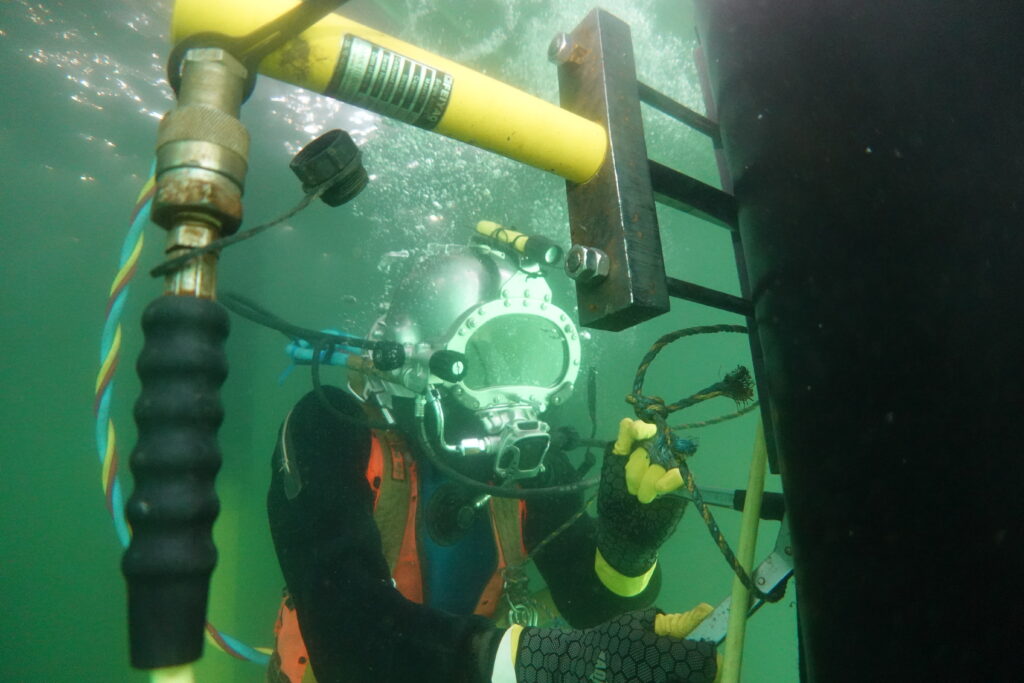

Colloquially referred to as an “underwater tradesman,” they provide a wide range of services from condition inspections of submerged structures, like jetties, to construction, demolition and repair work, ship surveys, hull maintenance, deep-sea welding, habitat mapping and environmental impact assessments.

The underwater environments in which they work are also incredibly diverse, ranging from coastal ports and harbors to offshore oil or gas rigs, river systems, inland dams, sewage farms and drinking water reservoirs.

“I always say we’re almost like an underwater trade essentially, but a bit of a jack-of-all-trades. We can be running pipelines for electrical cable or we can be cutting piles off and doing demolition of a wharf or just doing basic inspection work,” Pritchard says.

“One day we could be working offshore on a boat or working in a port on a ship, and the next day we might be traveling inland to dive in a river or a drinking water tank or inspecting the rubber gaskets on horse training pools.

“We do a lot of diving in sewage farms as well. I was trying to teach my 4-year-old about that the other day when he was asking what happens when the toilet flushes. I said, ‘Well, there’s sewage farms,’ and he was blown away by this. By the time I told him that Daddy actually dives in them sometimes, his eyes were the size of dish plates.” (Pritchard’s husband also dives; together they own a commercial diving company.)

The work of a commercial diver requires the use of large, heavy or potentially dangerous equipment, which brings its own set of hazards to an occupation already burdened with the risk of drowning, decompression sickness, encounters with unfriendly marine life and marine vessel movements.

This is why it’s so important for divers to undertake the training required to be certified through an organization like ADAS.

“Commercial diving is considered one of the most hazardous occupations out there due to the fact you are working in an environment (water) which cannot sustain life, meaning you are so heavily dependent on equipment, as well as good training and good safety systems,” an ADAS spokesperson says.

“Underwater safety relies on understanding the risks involved, having appropriate muscle memory achieved through thorough training, including emergency exercises and rescues, and knowing your equipment well enough to use it even when under stress or duress.”

While each diving course takes around one month to complete and costs upwards of 10,000 Australian dollars (AUD, or $6,700 U.S.), Pritchard said the time and financial investment is well worth it, with entry-level positions in the commercial diving industry paying around AUD 80,000 per year. Diving supervisors, a position requiring a separate course, can earn between AUD 100,000 and 130,000 ($67,000 to $87,000) depending on the company, while additional certifications covering areas such as confined spaces, rigging, qualifications as a coxswain or licensed commercial boat operator, could add even more to the salary.

While commercial diving is a traditionally male-dominated environment, Pritchard says ADAS are trying to break down barriers for women interested in entering the industry.

“I think things are changing,” Pritchard says. “ADAS are trying to promote female divers and support female divers. If female divers sign up to courses, they’re given a mentor to go through the system with, and I’m part of that mentoring group.”

Origin story

Pritchard’s first experience with diving as a young child came through her father, a plumber by trade and recreational diver who “liked chasing crayfish around” in the warm northern coastal waters off Queensland, Australia.

But it wasn’t until she was studying at Melbourne’s Monash University, in the southern Australian state of Victoria, that she began diving more regularly with friends and completed her recreational scuba diving certification.

Her hobby began to merge with her career when, after completing her bachelor’s degree, she scored a job as a marine biologist at a small company that, among other services, had a diving contract monitoring Victoria’s marine parks.

This role, which saw her spending plenty of time underwater, also brought her in contact with a commercial diving company that often needed a scientific diver to accompany them while completing marine pest inspections on vessels or reefs.

Eventually, this connection saw Pritchard take a career sidestep away from marine biology and into the world of commercial diving, working within the business’s management team as well as out in the water.

She completed her two commercial diving certifications through ADAS. These courses included training in the underwater use of welding and cutting equipment, pneumatic and hydraulic tools, salvage equipment, air and water dredging equipment and construction tools, and the certifications that allow her to dive to 30 meters with a surface-supplied breathing apparatus.

Since jumping into her underwater career, Pritchard has completed more than 3,000 commercial dives, most of which have been carried out in Victorian waters, and has supervised another 1,000 dives.

“If you want to get into commercial diving, you’ve got to love the water; you’ve got to love being on the water and around the water because we spend a lot of time on boats,” Pritchard says.

“I think people are either comfortable in the water or they’re not. As soon as you go underwater, some people don’t like it, they feel a little claustrophobic or you hear them saying, ‘I can’t do that. I feel like I can’t breathe.’ I don’t get that feeling at all, I just really enjoy it, but it’s not for everybody.”

Pritchard is also passing on her knowledge to her own group of employees. Six years ago, she and her husband started their company, Southern Divers.

It’s one of my happy places, because I get in and I’m just relaxed.

As the company’s managing director, Pritchard doesn’t spend as much time in a scuba suit as she used to, although she still loves getting out in the water as much as the job allows.

“I’m pregnant at the moment as well, so I’m not diving right now, but when I can I still get out and love to get in the water,” Pritchard says. “It’s one of my happy places, because I get in and I’m just relaxed.”

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.