“Don’t mention that you’re a journalist; it makes it complicated,” cautioned Wanbae Lee, head of a village near the border between North and South Korea. He had come to meet me near Imjingang, the final South Korean train station. There, a sign pointed toward Pyongyang, just 209 kilometers away, though no train tracks led in that direction.

Earlier, when I had tried to understand how to reach Lee’s village by car, the navigation application took me in circles through the streets of Gyeonggi Province. Other apps tried to redirect me to nearby tourist spots or seemed to exclude the village altogether, and photos and online street views were rare. Finally, after several calls, Lee decided to meet in front of the train station so I could follow him to Tongilchon, whose name means “Unification Village.”

Lee, a friendly man in his early 70s, is the village head and the founder of its unique souvenir shop. Wearing a simple shirt and a casual blue sweater zipped halfway up, he was calm with a warm smile and a touch of gray in his hair.

Lee instructed me to have my identity cards ready and then asked me to follow his car. We were heading to the DMZ, or Demilitarized Zone, a strip of land between North and South Korea about 250 km long and 4 km wide that was created to serve as a buffer zone between the two countries after the Korean War ended in an armistice 1953. The DMZ encompasses several villages, some of which are not fully open to South Korean visitors. But others, including Tongilchon, have opened up partially to tourists, offering new experiences for travelers and new job prospects for the villagers.

I followed Lee, and after crossing a bridge and passing through several checkpoints, we arrived at the Gate of Unification, where I received a visitors’ card, and then proceeded to Tongilchon, a village of about 100 houses, a church and a few government buildings perched atop a hill.

Finally, at a small square marking the village’s entrance, we found the business I had come so far to visit: the shop Lee founded three decades ago to sell souvenirs and refreshments in the DMZ.

Vegan ice cream and barbed wire

The shop sells T-shirts, hats, mugs, magnets, postcards, books and local agricultural products, with even the rice labeled “DMZ.” The most popular, says Lee, is vegan ice cream made with locally grown soybeans. The DMZ region is free of factories, which means the environment is pristine and ideal for growing crops.

The shop began as a collective effort funded with $300 in investments from village families. It grew gradually, adapting to evolving demands and capitalizing on opportunities like the surge in foreign visitors, and now provides an economic lifeline for the village. The influx of tourists drawn by the village’s unique location fuels a fragile economy and fosters a sense of connection with the outside world — and among the villagers. At the counter, a woman with a DMZ cap was talking with an old man who had come by to chat.

Government policies allowing visitors to enter the village played a crucial role in the shop’s growth, Lee says.

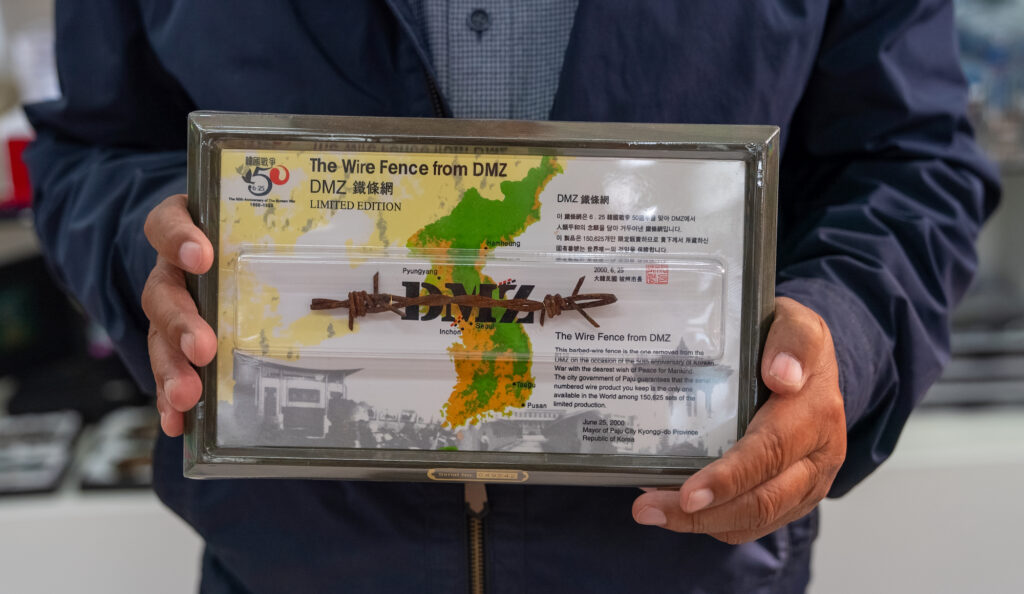

Besides the ice cream, one of his other best-sellers was inspired by the fall of the Berlin Wall. About 20 years ago, Lee had the idea to craft souvenirs from rusted pieces of barbed wire from the fences running through the DMZ. Although the other villagers were skeptical, he was determined that the souvenirs could stand as a testament to the region’s complex history and resilience.

“The remaining parts of the Berlin wall gained importance due to historical facts that they were carrying. I think that was the inspiration for me,” he says. “It’s not that easy to find the wire, though! You need to be a village citizen first,” he adds with a laugh.

Dreams of expansion

The souvenir shop enjoys a steady stream of visitors throughout the year. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, more than 1.2 million people visited the DMZ annually. Lee dreams of expansion, of broadening the product range and enlarging the shop, but opportunities are limited in the DMZ.

While most agricultural products, like beans and rice, are grown in Tongilchon’s own fields, the manufactured products come from trusted companies headquartered beyond the village’s borders.

The Covid-19 pandemic significantly impacted the business, causing a drastic decline in tourism. The number of foreign visitors to South Korea reached nearly 17 million in 2019, and then dropped to under 1 million in 2020. In 2023, this number had returned to 10 million. Relying solely on local customers, Lee temporarily turned to agriculture to supplement the shop’s income. However, with the easing of restrictions and the return of international travel, a cautious optimism has emerged, and the souvenir shop is once again open for business.

To Lee, the greatest challenge in the DMZ isn’t economic uncertainty. It’s the absence of friends and families, severed by a line drawn across the land. “Government policies, they come and go,” he says. “But what’s never changed is the fact that parts of our families are so close, yet so impossibly distant.” A scar cleaves his village in two, a painful reminder of a neighboring community lost to the other side of the border, making life in the DMZ a constant dance with the burdens of history.

As our conversation drew to a close, I finally broached the potentially awkward question of the shop’s earnings. But unlike many business owners, Lee wasn’t uncomfortable about answering. “It depends, but maximum, we earned $500,000 per year, which we share within our community,” he says. “We share our income together to grow the business.”

We exchanged farewells, and I got in my car, turned the engine on, and opened my navigation app to go back home. However, I soon realized it wouldn’t work inside the village. I was outside the Korean map.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.