In 1955, Tennessee Ernie Ford’s recording of “Sixteen Tons” was a No. 1 hit on the country and pop music charts in the United States. His finger snaps and deep baritone voice captivated audiences, as did the sympathetic portrait of hard-working coal miners, forever in debt to the coal company store.

You load 16 tons, what do you get?

Another day older and deeper in debt

St. Peter, don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store

The lyrics were a reference to the scrip system that was common in American coal towns in the early 20th century. Scrip was privately issued currency, usually in the form of metal tokens, redeemable only at the company store. Miners could “draw scrip” from the company in the form of tokens, essentially receiving credit against future wages.

Companies ordered the brass or nickel tokens by the thousands. They usually had the company’s name embossed around the edge and a value, from 1 cent to 1 dollar, in the center. The companies sometimes ordered tokens with a little flair. It could be scalloped edges or a hexagonal coin instead of a round one. Some scrip had a hole punched in the center that might be the shape of a star or triangle or even the first letter of the company name.

Scrip filled an important need in a place and during a time when cash was scarce. In the early 1900s, the strange little coins became a symbol of coal companies’ control over miners.

Company towns, company coins

Paying workers in scrip had its origins in England’s “truck system.” In the 1700s and early 1800s, factory owners and large landowners paid workers in groceries or cloth from their company stores. By the late 1700s, many employers had incorporated the use of tokens.

In his classic study, George Hilton notes several explanations for why the truck system emerged. One was the scarcity of government-issued currency. Another was the opportunity for employers to make a profit by offering cheap, shoddy goods at inflated prices. Such abuses led the U.K. Parliament to pass a series of laws, culminating in the Truck Act of 1831, which required payment of wages in legal tender. Over the next few decades, the law successfully eliminated the truck system in England. These laws were so airtight that they had to be amended in the 1950s before companies could pay workers by check or direct deposit.

Initially, the scrip system in the American coal industry was born out of necessity. Coal towns were often remote and cut off from regular commerce. The coal seams that run beneath the Appalachian Mountain Range were rich but effectively inaccessible until the construction of railroads across the region between the 1870s and 1890s. Even then, the early coal camps in eastern Kentucky, southern West Virginia and southwest Virginia were little more than men living in cabins in the wilderness. (Though companies would soon build wood-frame houses, churches and schools to attract families and create permanent communities.)

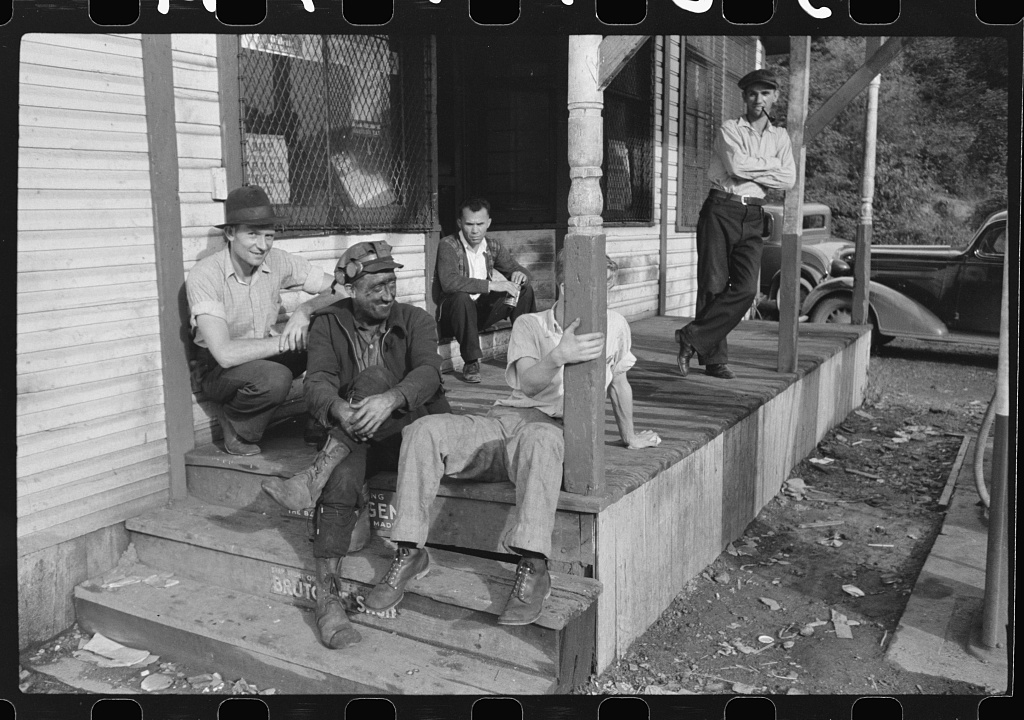

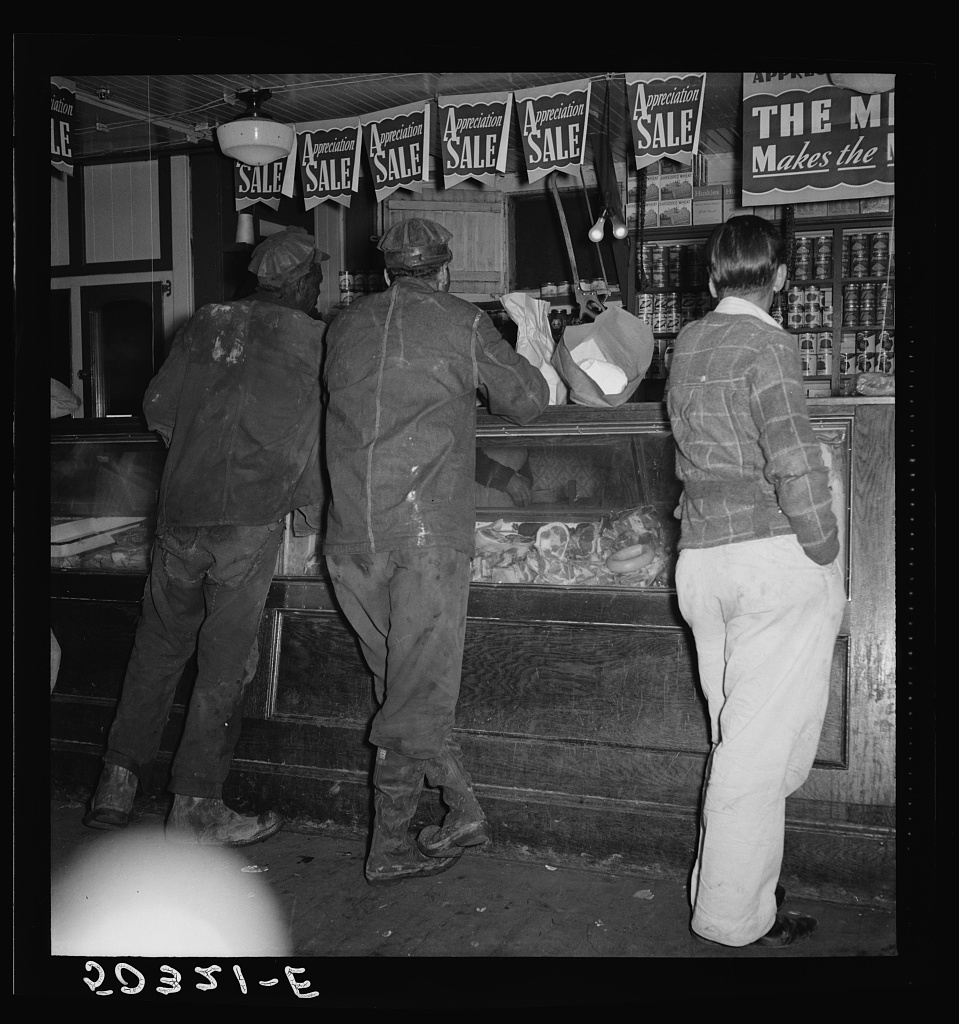

Still, being a long train ride from any major town or city, residents relied on the company to make consumer products available to them. Coal companies would construct the company store at the center of the town. Usually the largest building, it was often an imposing structure of brick and mortar, a symbol of the employer’s power. There, miners and their families could purchase basic necessities — sacks of flour and corn meal, a can of cooking oil — as well as clothing and household items of all kinds. The same store sold miners the very supplies they needed underground: pickaxes, shovels, helmets and carbide for their headlamps. When a young family arrived in town, the fully stocked shelves of the company store and an envelope of scrip eased them into their new life.

But there was a darker side to the company store and its easy credit. New employees were often charged for their transportation to coalfields, their pick and shovel, blasting caps and powder, first month’s rent and first week’s food, all before starting to work. This was sometimes a debt they could never repay on their meager wages, which meant that they would only receive scrip, never cash.

There were several high-profile cases of immigrants feeling trapped by this system. Italian and Hungarian immigrants who landed in Ellis Island would be recruited by a company agent and put on a train to the coalfields of Appalachia, only to suddenly find themselves deep in debt in a remote mountain town with seemingly nowhere to run. On multiple occasions in the 1890s and early 1900s, the Austro-Hungarian and Italian consulates demanded that the governor of West Virginia investigate accusations of debt peonage. These episodes typically ended with the company avoiding prosecution by allowing the immigrants to leave in search of another job.

When demand for coal dropped, miners would sometimes get only two or three days of work per week. They suddenly realized how dependent on scrip they had become. When miners tried to unionize in southern West Virginia in the early 1900s, the fiercely anti-union coal companies cut off their lines of credit at the store and evicted them from the company-owned houses.

Coal miner Fred Mooney wrote in his memoirs about being forever in debt even though he “led the sheet,” which meant that he was one of the top producers at his mine. He and his wife Lillian made a plan: The next time the mine was idle, Fred would go to other towns looking for a better job.

But by the next time Lillian went to the company store, the bookkeeper had heard that Fred was looking for another job and refused to extend any more scrip to Lillian. In a fit of anger, Lillian exclaimed, “Oh! I hope the union comes here, then you will pay wages, and we will get something besides scrip for Fred’s work.” When Fred got home, he found his wife in tears. He had been fired, and they had three days to pack their belongings and leave town.

The company store in changing times

Just as in England a century earlier, there was growing concern in the United States about the potential for abuse when employers paid workers in scrip. Critics said that when workers were reliant on a single retailer, the companies could charge exorbitant prices or sell inferior goods. Historians have debated the extent to which coal companies engaged in such practices. Some note that independent merchants often accepted scrip and exchanged it with the company for a discount. But most agree that the system left workers vulnerable to exploitation.

In 1918, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that scrip must be transferable and redeemable in cash, but the system persisted for decades. Several states passed laws prohibiting the payment of wages in scrip except for advances on future earnings. So many miners continued to need those advances, especially during the Great Depression in the 1930s, that the system flourished despite the laws.

Some coalfield residents have fond memories of their company store. Many were grateful for the credit during hard times. Others remember their local company store for its high-quality products. In Ernest, Pennsylvania, people remember their company store as having the best shoes and clothes around. Twice a year, a tailor would take special orders to custom sew fine Sunday outfits. When miners unionized and their wages increased, coal companies made a wider range of consumer products available, including hunting rifles, home furnishings and whitewall tires.

Merle Travis grew up in the coal towns of Muhlenberg County, Kentucky, in the 1930s and 1940s. As a young man, it was Travis who wrote the song “Sixteen Tons” that Ernie Ford made into a No. 1 hit. Travis took the famous line, “you load sixteen tons and what do you get / another day older and deeper in debt” from a letter his coal miner brother had written to him in the 1940s. For all that had changed, some miners were still struggling to stay out of debt to the company store.

But the scrip system was fading away. By 1947, one survey found that only 17% of the 260 mines still issued scrip. During the 1950s, mining employment in the U.S. declined dramatically, and some mines shut down altogether. Some mechanized, requiring only a fraction of the miners. Increasingly, companies sold off the company houses and closed the company stores.

Today, few company stores remain, but coal company scrip is plentiful. Scrip collectors regularly buy and sell pieces at flea markets and online auctions. They love the rarity of the coins, the variety in designs and the connection to an important part of the United States’ industrial past. For many, it is a connection to their hometowns and the companies that surrounded them in their childhood. They hold the tokens in their hands, read the name of the company and town, and recall the coal miners of another time.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.