Between the 18th and 20th centuries, most workers went from never thinking about the time to lining up at the factory entrance at the same time every day and “punching in” within a minute of starting time. Industrialists spent many years devising new strategies, policies and procedures to create standardized workdays. One of their most effective tools was a relatively simple device invented in upstate New York in the late 1800s.

Times gone by

Humans have sought to keep time for millennia. Mathematicians in the ancient world developed sundials to measure the passage of time. In the 11th century, Chinese inventor Su-Song constructed a clock for the emperor that was a 40-foot-tall mechanical wonder of its era. Around 1631, German clockmaker Johann Sayler crafted an astronomical clock with a power reserve that allowed it to keep time for up to three months — quite an achievement for its day.

And yet, most people throughout the world lived without clocks well into the 19th century. Farmers, fishermen, homemakers and craftspeople rose with the sun and went about their daily tasks. They lit candles and lamps when the sun set and laid down to sleep after their evening chores — rarely thinking about hours and minutes.

In a 1967 essay, historian E.P. Thompson noted that for European peasants, the day followed the necessary tasks of milking the cows early in the morning and harvesting grain while the sun was out, before the thunderstorms arrived. People’s daily schedules were set to nature, the weather and the needs of their livestock. As a result, their activities varied greatly from one day to the next and from one season to the other.

In a craftsperson’s shop, there was also great variation in daily tasks and the pace of work. Bad weather could interrupt the arrival of materials, slow business resulted in idleness, and some artisans kept up farming on the side, adding yet more variation to their schedules. In 18th-century England, “Saint Monday” was universally recognized as a day that started slowly and was as much about sharing tales of frivolity from the day of rest as it was about work.

The rise of industry

But then manufacturing technology began to change. As steam engines replaced waterwheels, the pace of production hastened, and workers were expected to keep up.

A lot of early factory work required continual effort. The fires of the forges and kilns could not be allowed to go out — otherwise precious hours were lost to relighting them. Bobbins of thread in the textile mills needed to be continually replaced lest the cloth be ruined. Production in most places had to be steady and running near capacity for the business to be profitable.

When early factory owners began recruiting workers from villages for jobs with standardized schedules, they had their work cut out for them. Workers had no prior experience with a timed existence, and they still expected to observe Saint Monday every week. Much of early industrialists’ efforts were spent on time discipline.

During the 1700s, clocks became more plentiful and more accurate. Factories would often display them prominently to enforce the timed nature of the workday. At the famous potteries of Josiah Wedgwood in England, the clerk of the manufactory had a very explicit job description: “To be at the works the first in the morning, and settle the people to their business as they come in.” The clerk was also to give “notice” to those who came in after the appointed hour and take “an account of the time they are deficient.”

Factory owners in the 1700s, like Wedgwood, developed procedures around the timed workday that shaped industry to the present day, with time clerks, written rules, time sheets, and a system of penalties and bonuses.

By the early 1800s, the timed workday was expected in almost every factory. In Troy, New York, Benjamin Hanks designed a large clock with multiple dials that let workers know the time and tracked production processes in his iron mill. In Lowell, Massachusetts, the textile mills adopted a system of bells to alert the young women who worked there when the gates opened, when breakfast and lunch were served, and when work commenced.

As factories switched from the water wheel to steam engines to power their machinery, the steam whistle replaced the factory bells. The loud whistles were audible in workers’ homes throughout a factory town.

Maxim Gorky, a Russian writer and activist, started his 1906 book “Comrades” with the line: “Every day the factory whistle bellowed forth its shrill, roaring, trembling noises into the smoke-begrimed and greasy atmosphere of the working-men’s suburb; and obedient to the summons of the power of steam, people poured out of little grey houses into the streets.”

But even with large clocks on display and literal bells and whistles, timekeeping required a clerk to carefully observe the arrival of the workforce, to issue warnings for tardiness, to record and calculate lost time, and to deduct amounts for individual workers’ pay. That began to change in the late 1800s.

The working clock

According to Brian Main, a time-clock collector and researcher in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the earliest patent for a time clock was issued in England in 1855, and some of the earliest models were made and sold in the 1880s in the United Kingdom.

Williard L. Bundy received a U.S. patent in 1878 and a decade later incorporated the Bundy Manufacturing Co., located in Binghamton, New York, with his brother Harlow. Their earliest model was the “key recorder,” which required employees to carry individual keys issued by their employer. During the 1890s, the Bundys developed time clocks that stamped timecards and, in 1899, they took over the Standard Time Stamp Company to expand their operation. In 1900, the companies merged with the International Time Recording Company (ITR), which became a world leader in the manufacture and marketing of time clocks. In 1911, ITR merged with two other companies to become the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, which was a forerunner of International Business Machines (IBM).

With the proliferation of time clocks, there was no need for a clerk to carefully watch arrivals, record times and issue warnings.

Now, employees arrived at the entrance, removed their timecard from the rack, inserted it in the clock and — thunk! — a stamp forcefully marked the time of their arrival on the card. This became known as “punching the clock,” and the workers often called the device the “punch clock.”

Within a decade, time clocks were ubiquitous. In the first engineering textbook, “Factory Organization and Administration,” published in 1910, Hugo Diemer wrote, “Practically every factory uses a time-clock for the purpose of registering the time of arrival and departure of employees.”

In a 1915 book about innovations at the Ford Motor Company, the author noted that it had 129 time clocks that had been supplied by the International Time Recording Company, and they were all synchronized to one master clock that was kept on “Western Union time.” The company timekeeper in charge of all the clocks visited each of them daily to make sure they were in proper working order. Six spare clocks were kept as backups in case one needed to be replaced.

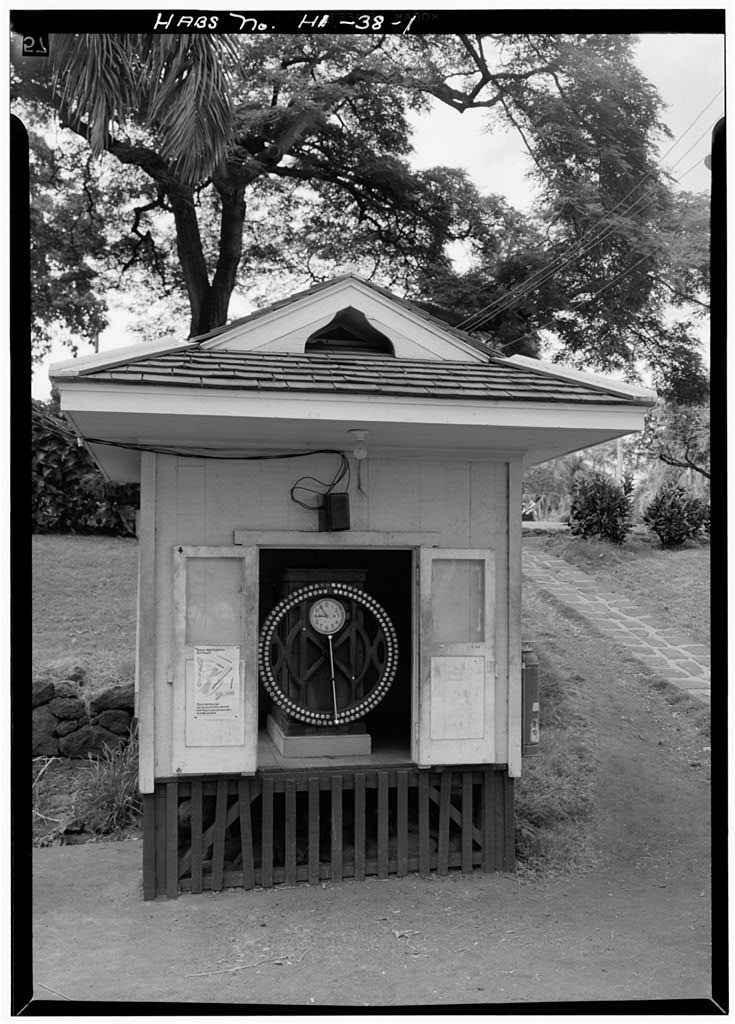

Time clocks proliferated around the world in the 20th century. Even in the tropical countryside of Maui, the Pioneer Mill Company of Lahaina installed one to track the hours of its roughly 1,600 employees. Founded in 1860, it was one of the oldest sugar cane mills in the Hawaiian Islands. The mill ceased operations in 1999, but preservation efforts are underway.

In Binghamton, the Bundy Museum of History and Art has 30 of Bundy’s time clocks on display in a permanent exhibit. With each new model, one can see how slight changes improved accuracy in timekeeping.

The modern era

The digitization of the timekeeping clock in 1979 enabled companies to automatically calculate an employees’ hours and pay.

Many companies, especially small ones, still use manual methods of time tracking, whether on paper or in a spreadsheet. The shift from paper timesheets to digital time tracking saves hours per year for both employees and managers, and reduces errors by as much as 30%. Managers only have to approve time sheets in an integrated HCM system; the program takes care of calculating wages and overtime.

During the early pandemic, as many employees were working from home for the first time, some organizations scrambled to figure out how to track time remotely. Some employers overreached, requiring workers to use monitoring software that led to privacy issues and poor morale.

Today the advanced options for clocking in offer high levels of security, ranging from PIN codes and QR codes to facial recognition, finger scans and voice commands. Biometric options discourage “buddy punching,” when one employee clocks in or out for another.

Even as most employers track workers’ hours digitally today, the effects of the punch clock linger. Even those of us who no longer have to stamp our time cards before leaving work still refer to “clocking out.”

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.