In December 1963, Cheri Register came home to Minnesota from the University of Chicago for her first winter break. She felt the need to reinvent her look with a blue work shirt from Montgomery Ward to fit in with campus radicals and express her solidarity with the workers of the world. When she told her father, who worked at a meatpacking plant, about her plan, he said that he could just bring her one from work.

He came home the next night with a blue cotton work shirt rolled up under his arm. Cheri was thinking that the older shirt would look more authentic and didn’t notice the grin on her father’s face. As she reached for the shirt, he let it unfurl, revealing that it was covered with pig’s blood from his work at the plant. She would later remember that as the moment she “truly left home.” She realized that she was a college kid who would “never have to take a job on the sliced bacon line.”

Back at school, when she wore the blue-collar shirt on her way to a white-collar career, it had a special meaning for her. Years later, in her memoir “Packinghouse Daughter,” she wrote, “I find that I still experience the world as a working-class kid away from home.”

The collared divide

The terms blue-collar and white-collar, which appear to have come into use first in the U.S., are widely understood to signify two very different kinds of jobs. Shirts with blue collars were work shirts, worn in factories, garages and mills. Shirts with white collars were worn by directors and vice presidents but also by accounting clerks and salespeople. Moreover, while women office workers were not as closely associated with white-collared shirts, their jobs were also considered “white collar.” Interestingly, in the 1970s, social critic Louise Kapp Howe coined “pink collar” to refer to nursing, teaching, and social work, because they were considered “women’s work,” and consequently paid lower salaries.

This collared divide of occupations was quite recent, emerging in the 1930s. This linguistic development followed on the heels of more than a century of changes in the nature of work and clothing.

Prior to industrialization, monarchs and the nobility distinguished themselves with elaborate starched, ruffled collars. The more elaborate the attire, the more apparent that they performed no manual labor. However, the rise of a new middle class of merchants, factory owners, and professionals changed notions of work, and social climbers who had to work for a living still strived to appear refined and wealthy.

Critics of the new middle class, like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, saw little difference between the emerging middle class and the old nobility. Marx and Engels wrote in the 1848 “Communist Manifesto,” “The modern bourgeois society that has sprouted from the ruins of feudal society, has not done away with class antagonisms. It has but established new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle in place of old ones.”

Others saw a dynamic new economy where commoners could rise from rags to riches. Scottish-born author Samuel Stiles penned the 1859 book “Self-Help,” which was intended to be a practical guide to upward mobility for young strivers. It sold a quarter million copies over the next five decades. Stiles places great importance on cultivating strong moral character within and notes that “brave and gentle character may be found under the humblest garb.” Yet, the book also implies that integrity when combined with self-improvement would often lead to material success.

In America, Horatio Alger wrote a series of novels featuring boys who rose through the ranks, often assisted by a chance meeting with a successful businessman. His 1868 novel “Ragged Dick” was about a reckless bootblack who smokes, gambles and drinks away his money until a well-to-do man gives him a great opportunity: a new suit of clothes and a job in his counting room. Soon, Dick learns the value of thrift and hard work and drops the name Ragged Dick, becoming known as Richard Hunter, Esq.

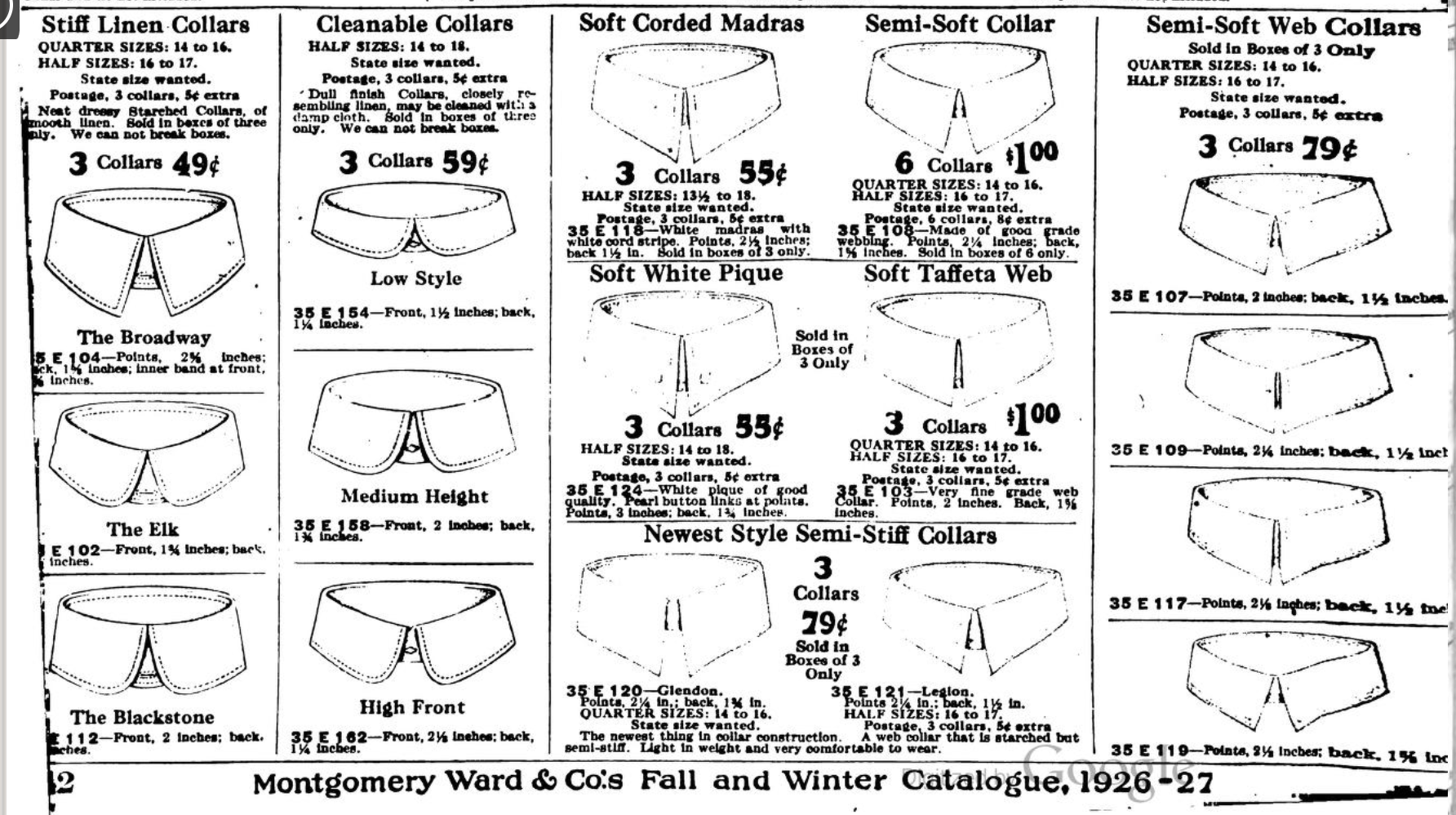

Many strivers attempted to make a similar transformation on their own, and proper attire was important. The detachable white collar first became widely available in the 1830s, allowing clerks and shopkeepers — who still had to do manual work from time to time — the ability to have a clean, freshly starched collar at all times.

For example, Henry Clay Southworth, a clerk in New York City in the 1850s, noted in his diary that he returned home late to get a fresh collar, having spent a hot June morning sweating through his first collar. That afternoon, if given the opportunity, Southworth could have blended in with the city’s wealthy businessmen. Historian Brian Luskey notes the tension that such clerks experienced. To them, the white collar was a vital symbol of their middle-class respectability.

By the 1890s, the number of clerical positions in industrialized societies had exploded. While an 1860s counting room might have only a handful of managers and clerks, the next few decades would witness the proliferation of office jobs — telegraph boys, steno girls, typists, secretaries, file clerks, salespeople, accountants and receptionists to name a few.

In 1951, famed sociologist C. Wright Mills published “White Collar: The American Middle Classes.” In it, he charts the decline of the old middle class of small business owners and the rise of professions and bureaucracies. Like “Organization Man,” another sociological study of the time, and the novel “The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit,” “White Collar” expressed a concern that the pursuit of status and success might come at the loss of community and core values.

The blue collar has a much shorter history. In the 19th century, working-class men often owned very few shirts that had no collars on them. (See Lewis Hine’s photograph of Russian steel workers.) Etymologist Barry Popik found that the term “blue collar” started to appear regularly in print in the mid-1920s as a contrast to white-collar occupations. It appeared in the Merriam-Webster dictionary in 1946 and in the Oxford English Dictionary in 1950, attributed to American origins.

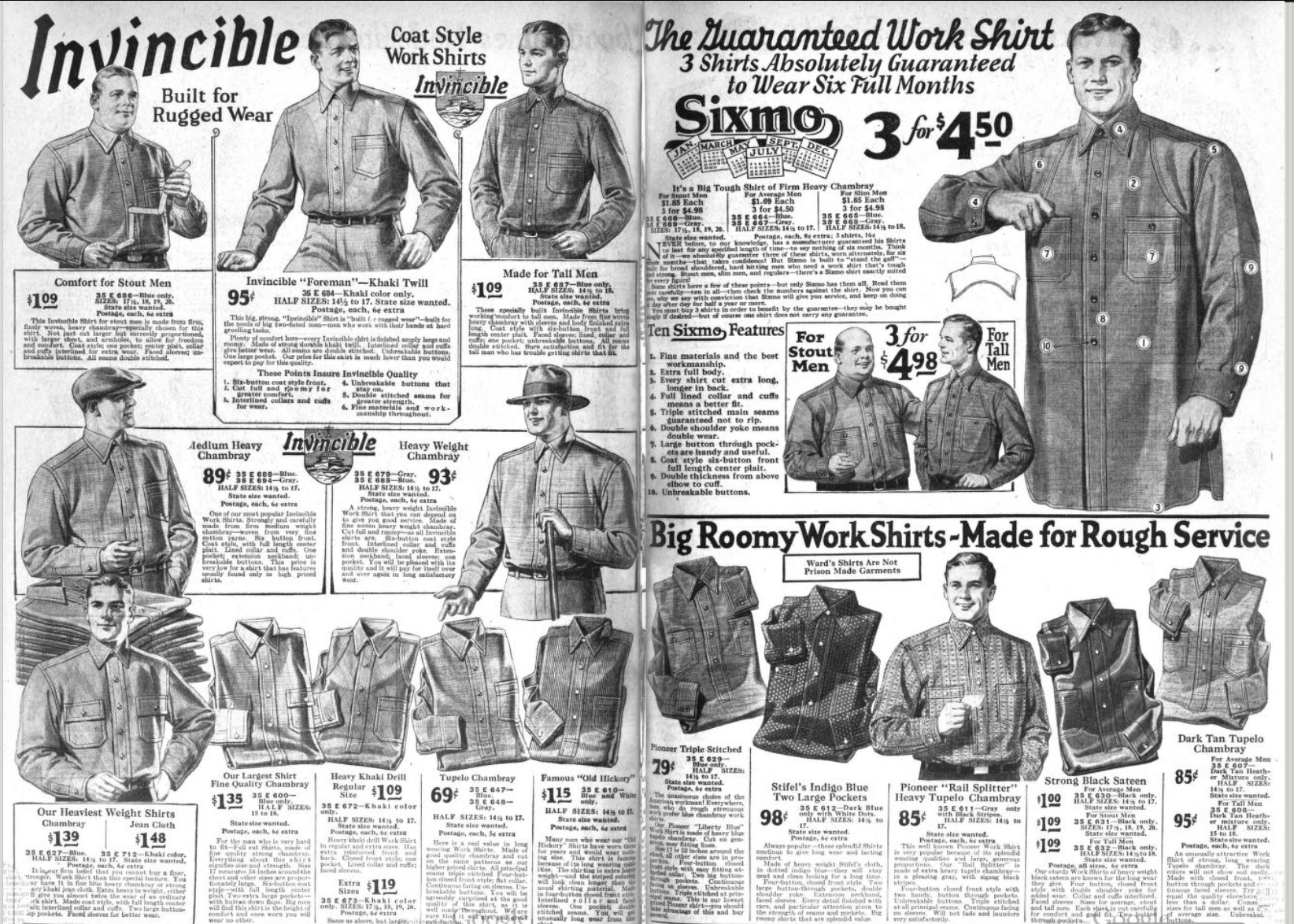

By the mid-1920s, collared work shirts were being mass produced cheaply enough to include pockets, collars, and cuffs, and industrial workers by that time could often afford to buy more than one. The 1926 Montgomery Ward mail-order catalog featured the “Guaranteed Work Shirt,” described as a “big tough shirt of firm heavy chambray.” It came in two colors. Buyers’ first choice was blue and second was gray.

By the 1940s, it was common for Americans to juxtapose blue-collar and white-collar jobs. In 1945, when the United States was still at war with Japan, Rear Admiral F. G. Crisp testified before Congress about the U.S. Navy’s need for more civilian workers to fill a variety of positions. “The Navy’s civilian employees fall into two broad groups, blue-collar workers and white-collar workers,” Crisp said. “Blue-collar workers, in general, are those who produce with their hands.” He listed mechanics, welders, electricians and laborers among them. White-collar workers, Crisp said, included “not only typists, stenographers, and file clerks” but also executives, engineers, and scientists.

By the 1940s, it was common for Americans to juxtapose blue-collar and white-collar jobs.

In the 1960s and 1970s, blue-collar workers and their families became nearly as popular subjects for social scientists as white-collar workers were in the 1950s. Sociologist Mirra Komorovsky’s 1964 “Blue-Collar Marriage” was one of the first sociological studies to explicitly analyze “blue-collar” life, and by 1971, economist Sar Levitan’s book “Blue-Collar Workers” was contending that they comprised “Middle America.” Sociologists also appreciated the convenience of the labels and often compared and contrasted attitudes and values of people in the two categories.

Scholarly studies of social classes appear to have helped popularize blue-collar and white-collar beyond the United States as in the 1969 volume “The Sociology of the Blue-Collar Worker,” which includes chapters on blue-collar workers in Italy, India, Peru, Argentina, Germany and England.

Rethinking labels

But big changes were on the horizon. Beginning in the 1970s, Europe and the U.S. entered a period economists named deindustrialization. Automation and plant shutdowns whittled down great armies of industrial workers to skeleton crews. Workers in the remaining steel mills were more likely to use computers in control rooms than scarfing torches or shovels.

Furthermore, the next wave of innovation in the office was led by a motley crew of hippies and college dropouts. In Microsoft’s now iconic 1978 employee photo, Paul Allen wore the only white collar, but he also sported a big beard and long hair. While IBM may have been known for its white shirts and black ties, dot-com era industry leaders like Google have focused on creating comfortable “dress for your day” environments, bringing T-shirts and jeans into the office.

Today, safety concerns have influenced the dress code of many traditionally blue-collar jobs. Whether in the warehouse or factory, on an oil rig or in a coal mine, workers are likely wearing high-visibility fluorescent and sometimes reflective shirts and jackets. The blue work shirt has become something of a rarity on the job, more often being part of a uniform for sometimes public-facing workers like delivery drivers and mechanics.

Meanwhile, the blue collar has grown in popularity beyond the blue-collar workplace. Troy Patterson, writing for the New York Times, sees it being worn by the woman who wants an effortless cool and by the “modern bro about town.” Patterson writes, “The blue chambray shirt is emblematic of a phenomenon that shows no sign of receding — the ever-accelerating chic of ‘yesterday’s blue-collar brands.’”

Perhaps somewhere right now there is a college student wearing a parent’s fluorescent vest to a campus rally and majoring in computer science in hopes that they will someday be able to wear T-shirts in their office.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.