In 1991, an experiment started in Ithaca, New York, a town of 32,000 about a four-hour drive from New York City. Paul Glover, a community organizer who had been an urban studies professor at Temple University, had 1,500 Ithaca Hours notes printed. On the front of his new currency was an engraving of nearby Lick Brook Falls. A banner over the image read “In Ithaca We Trust,” and below it: “One Hour.”

What followed was a surprisingly successful attempt to create a time-based community currency.

Glover had a variety of concerns that he hoped Ithaca Hours would help address. First, when residents and visitors alike spent their dollars in town, much of that money left the community as corporate profits or tax dollars, which were spent elsewhere.

“We printed our own money because … [Ithaca Hours] stay in our region to help us hire each other,” he wrote. Homeowners could hire a repair person and pay for their labor in Ithaca Hours, and in turn, some 500 businesses, including a credit union, accepted the notes as the equivalent of $10 per Ithaca Hour. At their height, homeowners could even use Ithaca Hours to make mortgage payments at the credit union.

An early gathering of Ithaca Hours members in 1991. Courtesy of The History Center in Tompkins County

Origins of time-based currencies

Glover was inspired to create his time-based currency after learning about similar systems introduced in the United States during the 1820s and 1830s. Those decades witnessed the rise of manufacturing, wage labor and a cash economy, as well as growing anxiety about where those developments might lead. These worries produced a flurry of ideas, including new cooperative communities — such as Shaker villages — based on communal property and gender equality.

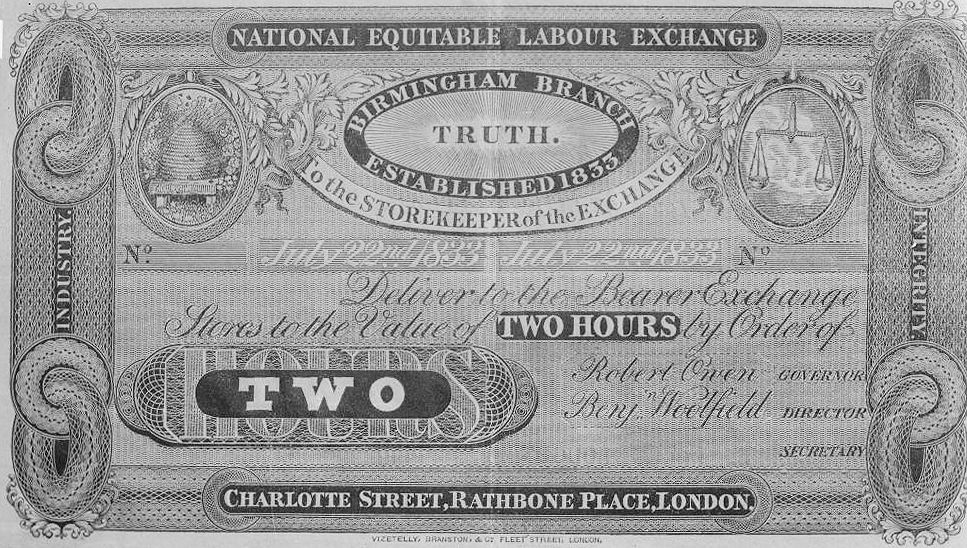

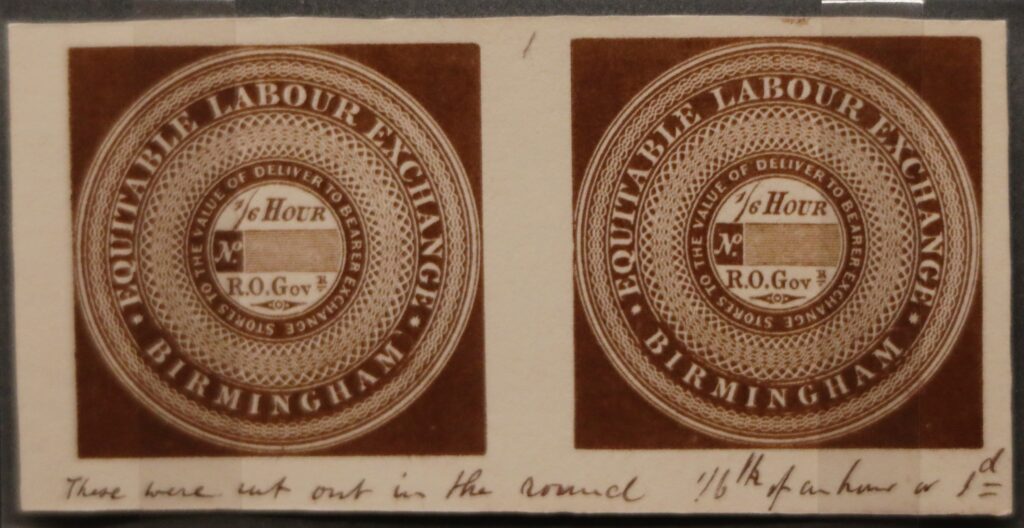

One such would-be utopia was Robert Owen’s community of New Harmony, Indiana. Owen had made his fortune as a textile mill owner in Scotland, and like many, he paid his workers in scrip that was redeemable at the company store. While Owen offered quality goods at fair prices, most industrialists used the system as a way to control and exploit their employees, eventually leading Parliament to outlaw the use of scrip beginning in 1831.

Owen wanted to go the other way, creating a self-sufficient model community where residents invested in a cooperatively owned enterprise and earned credit at a community store through their labor. In 1825, he bought New Harmony to launch his experiment. After a few years, the project had failed as a social reform enterprise but had succeeded in creating an important center for science and research. The town attracted sincere, hardworking people, but also some “crackpots” that contributed to its downfall, one historian observed.

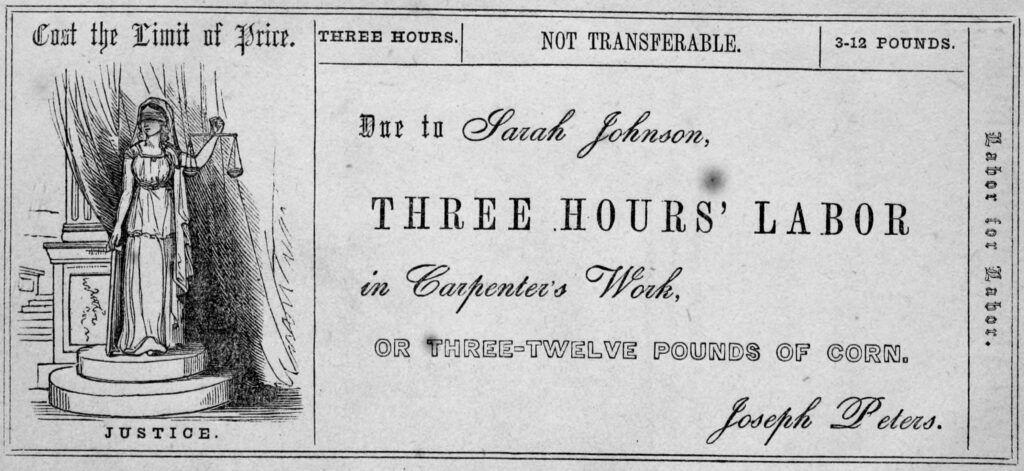

One disappointed New Harmony resident was Josiah Warren. Warren wanted to carry on certain aspects of the experiment, but he believed one of New Harmony’s fatal flaws was its reliance on communal ownership. Warren would become known for two things. One was being an early evangelist for individual sovereignty and personal property. The other was his experimental Cincinnati Time Store, which he started in 1827.

The store’s first innovation was that Warren priced his goods at the costs incurred plus 7%. The idea was that goods should only be sold at the cost of the labor to make them, which was known as the labor theory of value. The 7% was to cover his labor for handling the goods, but the system was supposed to prevent people from making a profit beyond the cost of the labor that went into it.

The second unique aspect was a system of “labor notes” that Warren created based on hours of labor. The store had a board where customers could advertise what kinds of labor they needed or would perform, such as carpentry or farm labor. Like Ithaca Hours, a worker could earn more notes based on the difficulty of the labor. That was, incidentally, one of the flaws of the system — the idea that not all labor was equal.

When asked if he created the idea of time currency, Warren bristled. He did not “consider any man the originator of principles or truths,” he wrote. “We only discover and develop them.” Believing the experiment had been a success, Warren closed the store after three years to move on to other projects. This would prove to be a weakness of later time-based currencies: They have often depended on the time and efforts of their creators.

Japan’s time bank

More than a century later, another freethinker began an experiment in exchanging goods and services for time. Teruko Mizushima, the daughter of an Osaka merchant, gave birth at the start of World War II and was soon facing wartime food shortages. To get fresh vegetables, she offered to sew clothing for neighbors who were themselves struggling with clothing shortages.

After the war, Mizushima gained renown for a 1950 newspaper article describing a labor bank, explaining the possibility of a time-based currency and a bank that would enable the exchanges. In the years that followed, she became known for her social commentary and for speaking on national broadcasts. In 1973, she created the Volunteer Labor Network.

Within five years, the network included about 2,600 members. Many of them — but not all — were housewives like Mizushima. She ran the network from her home and organized the members into local branches to facilitate the exchanges. Over the next five years, several hundred more people joined the network. Volunteers exchanged nearly 500,000 hours of volunteer labor. But the organization relied heavily on Mizushima to keep it running. When she died in 1996 at the age of 76, the network declined in members.

But her idea inspired others in Japan. In 1991, Tsutomu Hatta, a retired attorney general, proposed a time-based currency as a solution to the need for elder care in a nation with a rapidly aging population. In 1994, a group of organizers and attorneys produced a report based on the idea, announcing fureai kippu (caring relationship tickets) and an associated fund. They hoped to attract 12 million volunteers who would accrue hours by shopping for the elderly or helping with everyday tasks. Volunteers could use those hours to pay for services for their parents who might live in another part of the country — or save them for when they got older.

According to engineer and economist Bernard Lietaer, Japan experienced a boom in community currencies in the 1990s because of the 1990 economic crash. The Fureai Kippu network, for example, grew to have some 372 branches across the country and likely fell short of its goal of attracting 12 million volunteers, but many other community currencies started in this same period. One recent study identified 792 community currencies in Japan. When researchers surveyed organizers about the reasons the currencies had been created, the top four answers were “creating connections among people,” “regional economic revitalization,” “promotion of recycling,” and “natural environment protection.” These reasons were far different from the first time-based currencies of the early 1800s, which leads us back to Ithaca Hours.

Ithaca and beyond

While Josiah Warren and Robert Owen were concerned about the exploitation of laborers when they introduced time-based currencies, the creators of the new currencies in the 1990s, like Paul Glover, were motivated by other issues. Glover mentioned wars and rain forests. Just a few years earlier, in 1987, the United Nations had issued a report known as the Brundtland Report that was an early articulation of the challenge of sustainable development. International economic development was supposed to alleviate poverty, raise standards of living and reduce conflict, but it also brought ozone depletion, global warming and worsening food insecurity.

That same year, Glover wrote an op-ed in a local Ithaca newspaper warning about the disappearance of farmland because of suburban sprawl and rapid population growth. One answer, he suggested, was to create local food systems. “How well could New York live from its own backyard?” he asked.

While Ithaca Hours proved successful for more than two decades, the currency’s use declined when Glover moved away from Ithaca.

And although many proponents of time-based currencies are thinking locally, others are thinking globally. In 2012, Gabriele Donati and Karim Varini, two friends from Switzerland, started TimeRepublik, an online bank dealing in TimeCoins, each earned with 15 minutes of labor. Nearly a decade later, Donati told an online magazine journalist he and Varini had been inspired by a news story about tenants of an apartment building who exchanged favors and had the superintendent log them.

“This caught our attention, because for years we’ve been talking about creating an alternative space that could value relationships rather than transactions,” he said. “A place based on reciprocity and abundance rather than hoarding and scarcity.”

Now TimeRepublik has 100,000 users worldwide. While experiments such as the Cincinnati Time Store, the Volunteer Labor Network and Ithaca Hours have fallen by the wayside, the continued interest in time-based currencies suggests Josiah Warren may have been onto something.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.