You’re a busy parent in the 1980s, trying to buy some milk at the store while holding onto a screaming toddler. When it’s your turn to face the cashier, you realize you’re out of cash. You’ve got a checkbook in your bag, but there’s no way you can write intelligibly with the child in your arms. Thankfully, your checkbook cover also has a slot for your debit card, and you can swipe your way out of the situation.

Debit cards are an innovation we take for granted today, but when they debuted in the 1970s, they were a novel concept. Faced with long queues at bank branches, financial institutions had already begun digitizing payroll and sending wages directly into bank accounts. But people needed to be able to pay directly from their bank accounts, too.

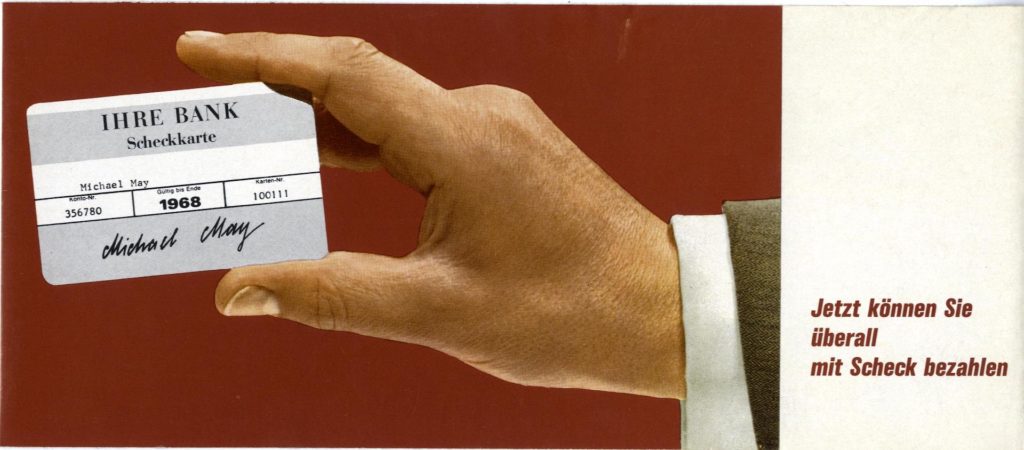

Before the debit card, banks were making steps in this direction with credit card imprinters, check guarantee cards, and activated cash withdrawals using credit cards or what were then called ATM cards. These were the same size and material as credit cards but only worked with automated teller machines (ATMs) of a single network.

But none of those options offered real-time confirmation that the customer was good for the money — until the debit card.

Early history

Debit cards were launched on the back of credit infrastructure. With roots in late-19th-century store credit, the idea of credit cards was very appealing to U.S. banks, which started experimenting with cards in the 1940s. Bank of America launched the first successful roll-over credit card in California in 1958. The credit system spread internationally from 1966 onwards, first in Britain and then in Canada, Mexico, France, Japan and Spain.

As documented by tech sociologist and historian David Stearns, in early 1971, the American Bankers Association (ABA) endorsed the magnetic stripe (or magstripe) as the preferred method for making plastic cards machine-readable. ATM manufacturers had integrated magstripe solutions as early as 1967. The ABA eventually supported IBM’s 360 equipment solution and defined a format for encoding a customer’s account information on a magstripe.

The magstripe had the potential to transfer authorization requests and details about the purchase to the bank’s computers from the point of sale. But early magstripes could not hold very much information — just the customer personal identification number (PIN) and a transaction limit. This amount of information worked well for ATMs but not for shopping.

And at that time, point-of-sale (POS) terminals for on-the-spot card transactions weren’t widespread in retail. Some of them cost as much as $1,000 each. Card authorizations required manual work, with the cashier making a phone call or comparing the card number to a booklet listing all canceled cards. Either procedure resulted in minutes-long authorization times, and they did little to help with non-local fraud detection.

Not surprisingly, consumers were still using cash and personal checks for most purchases. Indeed, a report commissioned by the Federal Reserve Bank in Atlanta in 1971 found that the public was overwhelmingly against any kind of electronic payments system.

Moving forward

Undeterred, retailers and banks continued looking for alternatives for electronic payments. In October 1971, the City National Bank and Trust of Columbus, Ohio, began what they called an “electronic funds transfer pilot test.” The experiment received a lukewarm response from consumers, but it inspired Dee W. Hock and Tom Honey to work on what was to become Visa’s debit card. Called Entrée in the pilot project, it was first introduced in 1975, again in Columbus, Ohio. The system linked merchants with the Visa data center in California, offering real-time confirmation that the card was good.

Banks, computer manufacturers and card companies established an International Organization for Standardization (ISO) common standard for encoding plastic cards in 1976. Rules for character embossing, card size and magstripe information helped stimulate the development of inexpensive POS terminals with phone connections. The Hawaiian company Verifone’s ZON device released in 1983 became the benchmark for modern card terminals.

Only a handful of banks had issued debit cards during the 1970s, and generally banks were not enthusiastic about promoting POS terminals.

In the spring of 1981, for instance, a survey by the ABA’s Operations and Automation Division reported that three-quarters of the surveyed banks had neither installed nor had any plans to promote installing POS terminals with their merchant customers. Debit card transaction volume and cardholder base remained minuscule through the 1980s.

But global interest in electronic payments was growing as international standards for payment cards and POS terminals became more common. Payment card penetration had substantially increased, and computer advancements enabled national and international authorization systems.

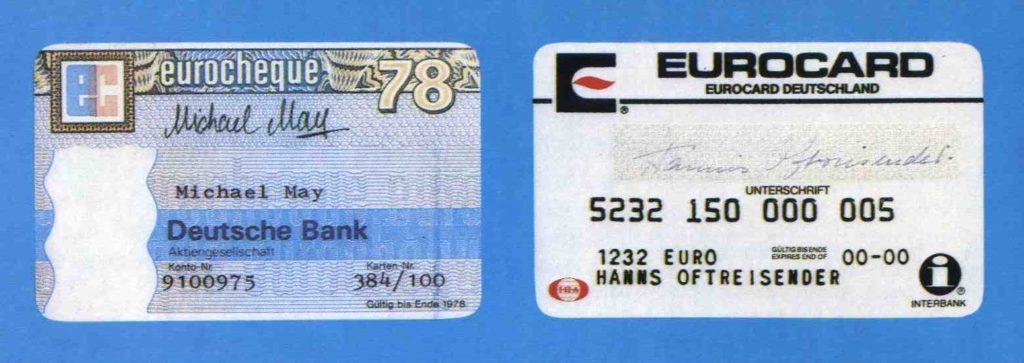

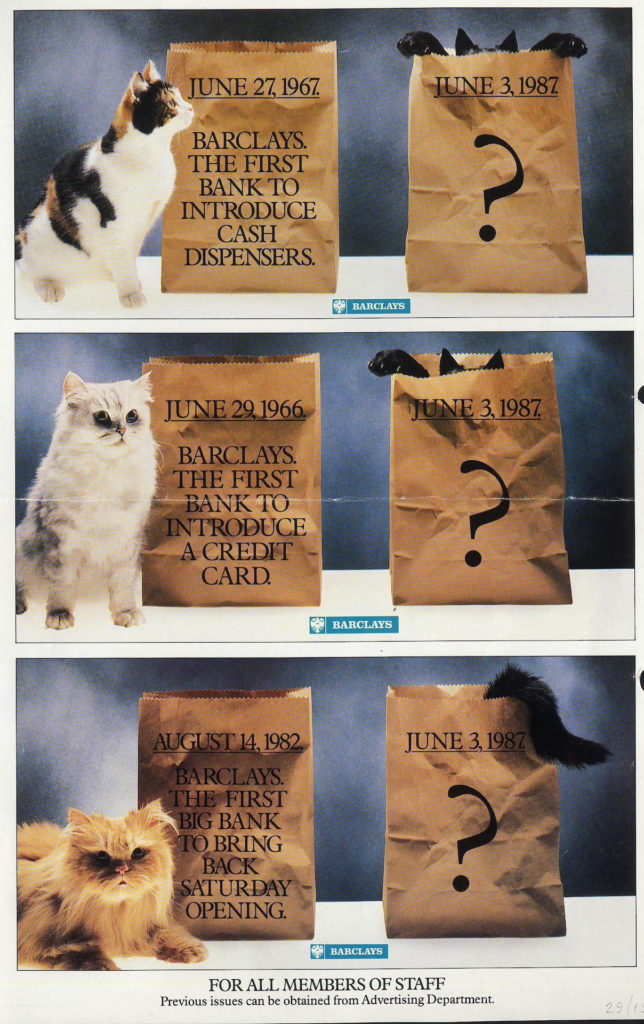

Banks across the globe used the established credit card authorization infrastructure and a widespread POS terminal network to turn their check guarantee cards into debit cards. In Spain, the savings banks turned their Tarjeta 6000 into a debit card in 1976, while in the U.K., Barclays launched Connect (later Visa Delta) in 1987. Starting in 1991, German consumers could pay with EC (eurocheque) cards in many retail outlets.

Magstripes were very easy to clone, but adding a microchip increased security. The chip card was a 1975 innovation by Roland Moreno in France, which he quickly determined would be useful for payments. France Telecom embraced chip cards for payment on public phones.

Mastercard’s initial worldwide deployment of cards with chips, a project called Mondex, introduced stored-value chip-and-PIN cards. Mondex as a product didn’t take off, but the chip-and-PIN concept was proven. European banks started adding chips to debit cards in the mid-1990s, and the technology became mandatory in Europe in 2005, in the U.K. in 2006, and in the U.S. in 2015.

There was still more a debit card could do. Citibank launched a prepaid debit card when it acquired payroll processor Ecount in 2007. In 2006, an estimated 4 million-plus U.S. workers had payroll cards. A decade later, that number had increased to 8.7 million. In the U.S., payroll cards have the same consumer protections as traditional debit cards. Prepaid and payroll cards don’t require individuals to have convenient access to a bank account like debit cards do. In addition, they eliminate potential check-cashing fees, making payroll more equitable and increasing financial inclusion.

State of adoption

Why did it take so long for the issuing banks to become interested in debit cards? Well, for one thing, many executives of the 1970s and 1980s saw electronic fund transfers as a competitive banking service — something that would differentiate them from their rivals. Most of these banks were building out ATM networks, which was a capital-intensive endeavor.

But developing credit card infrastructure was even more expensive. Rolling out a debit card would mean the end of much of the income paying for this credit card infrastructure: namely the “float,” or delay between a customer’s purchase and crediting the merchant.

Plus, the credit card business was on the asset side of the bank’s balance sheet. Credit cards were a lending product, while debit cards were a liability-side product, alongside deposits and checking accounts. Executives on the liability side had no interest in dealing with Visa or Mastercard, which delayed the sharing of ATM networks.

But in the 1990s, after banks had recouped their initial investments in ATMs, debit cards started looking more appealing to executives. Debit card use grew alongside the worldwide adoption of interconnected ATM networks.

With the rise of easy credit lines and mobile payment apps, are debit cards still necessary? It sure seems so.

The pandemic led to an increase of debit card payments worldwide, as contactless purchases gained appeal. In Germany, traditionally a cash-happy society, girocard payments jumped by nearly €1 billion over the course of 2020, an increase of 21.7% from 2019. In the Netherlands, debit card transactions accounted for 79% of all retail purchases in 2020, overtaking cash payments in all sectors for the first time. Debit card payment volumes jumped by upwards of 20% in the U.S. and the U.K. as well.

The next time you use plastic to pay for your groceries or make a purchase online, take a brief moment to think about all of the people who worked so hard for you to access your paycheck wherever you are, whenever you want.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.