“Children have always worked, but it is only since the reign of the machine that their work has been synonymous with slavery,” John Spargo wrote in his 1906 book, “The Bitter Cry of Children.”

The British political writer came to the United States shortly after the turn of the century, and there he witnessed some of the worst effects of industrialization. He was well aware of the long history of child labor in England but was moved to write an exposé by what he learned in America.

On a trip to Pittston, Pennsylvania, he met some “breaker boys” who spent their days sitting by a conveyor belt, watching chunks of coal slide pass. Their job was to spot chunks of slate among the coal and pick them out. If they missed one, it was common for the foreman to throw the slate at the boy who missed it.

This was one of the worst forms of child labor, with children breathing in coal dust and sometimes getting caught up in the conveyor belt while reaching for a piece of slate, which could result in mashed fingers or worse.

Spargo asked one of the boys in Pittston how old he was. “He certainly did not look more than 10 years old,” Spargo wrote, “but he answered boldly, ‘I’m 13, sir.’”

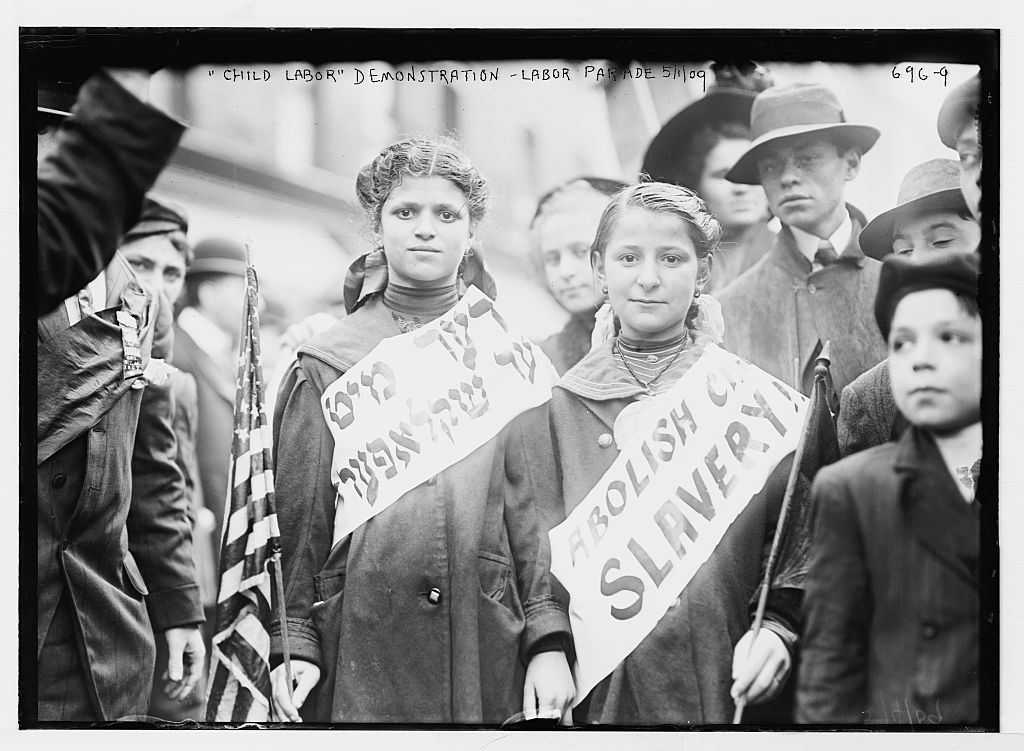

Such was the state of child labor in the U.S. in the early 1900s, and Spargo was one of many trying to get better laws enacted to end the worst abuses.

Children in the mills and mines

“Child labor” as an area of concern emerged as Europe industrialized in the 19th century. In farming societies, children had always worked beside their parents in the fields and in the home. Craftspeople in medieval cities employed their children as helpers, often fetching supplies or running errands. And some early factories like the potteries of Staffordshire employed whole families, with fathers acting as crew chiefs.

The rise of textile mills in England brought a new kind of child labor. Up to this time, contracts with child apprentices were the norm, and there were no laws to prohibit child labor. By the 1830s, companies were employing children directly, no longer under the supervision of a parent. In factories, child workers were no longer just helpers — they were a key component in the production process. That meant production depended on them doing their jobs continuously and quickly.

This new form of child labor in factories spread with industrialization because children were paid low wages, and factories were often desperate to find workers. Some employers also claimed children had an advantage because of their small, nimble hands.

Many reformers were aware that children were vulnerable in factory settings under the supervision of strangers, but perhaps none more so than Charles Dickens. He knew all too well the potential for harm. At age 12, when his father was sent to debtors’ prison, he was sent to work at Warren’s Blacking factory, pasting labels on shoe polish pots. Exploited and abused children became a hallmark of Dickens’s stories of industrial England, helping to raise awareness about the problems facing child workers.

One of the most serious concerns was safety. Not only were children facing the same risks in mines and mills as adults, but sometimes they were put in even greater danger because of their small size. In English novelist Frances Trollope’s 1840 book, “The Life and Adventures of Michael Armstrong, Factory Boy,” she described the work of the scavenger, a young girl who clears debris away from under the whirring, hissing power loom while it was running. As she creeps under the machine, the girl’s trembling body and head must be perfectly flat on the floor to avoid being sucked up into the loom.

England’s 1833 Factory Act set the minimum working age at 9 and required that all children have two hours of school each day. Previous laws had attempted to impose many of the same restrictions, but the 1833 act was the first to create an inspection system. Yet, even these tepid measures were only poorly enforced. Subsequent laws also restricted hours for women as well as children, to 10 hours a day in 1847.

Education and compulsory attendance

The 19th century brought expansions of factories but also schoolhouses, with the emergence of universal public education. In the northern U.S., states passed a series of compulsory school attendance laws, driven by the idea that education was important to citizenship in a republic. By the 1870s, Germany and France had passed similar laws, and in 1870, the British Parliament passed the Elementary Education Act, requiring children between 5 and 10 to attend school. In the 1920s, the newly formed Soviet Union passed similar laws.

Increasingly, reformers were just as concerned about children being deprived of an education as they were about children sustaining injuries in a factory. When American labor activist George McNeill became head of the Bureau of the Statistics of Labor in Massachusetts, one of his first reports, 1875’s Schooling and Hours of Labor of Children, opened with the declaration that 60,000 children were “growing up in ignorance,” in violation of state law.

In the late 19th century, working-class men in parts of Europe and North America — where factories became the dominant form of manufacturing — began to support further restrictions on women’s and children’s working hours. It was part of their campaign for a “family wage,” or pay that was high enough for a man to support a homemaker wife and children who stayed in school. While different countries had varied visions of women’s employment, there was an almost universal desire to keep children out of factories and mines until they reached their mid-teens.

At the same time, middle-class families were strategically maximizing their children’s — especially their sons’ — education. That meant having fewer children. One study of middle-class families in New York in the mid-1800s revealed that the average birth rate declined from about 5.8 children per family to 3.6 in just one generation. On the farm, having too few children limited the family’s ability to plow fields and harvest crops, but for middle-class families in town, fewer children meant more resources for the education of each child.

A progressive focus on child labor

The Progressive Movement emerged in the U.S. as problems of industrialization and urbanization became undeniable. Plus, more and more women were earning college degrees but being shut out by industry. As a result, they turned to careers in reform organizations, settlement houses and government agencies. Drawing on their traditional roles as mothers and housewives, they carved out areas of expertise in sanitation, education and child rearing. This gave them greater authority when trying to eliminate child labor.

The National Child Labor Committee formed in 1904 and had a board of directors that included famous reformers Florence Kelley and Jane Addams. The committee’s 1904 report found that, despite decades of efforts to curb child labor, some 2 million children under the age of 15 — more than 7% — still toiled away in mines and mills.

Among the committee’s most powerful weapons in the fight against child labor were the photographs of Lewis Hine. Hine had studied sociology at Columbia University in New York City before being hired by the committee to expose the child labor that was largely hidden from the public. He traveled to the coal mines of Pennsylvania and West Virginia and the textile mills of the U.S. South to take portraits of children at work. Hine’s photos often captured the exhaustion of the children and juxtaposed their small bodies standing in front of large machinery or blackened with coal dust.

Legislation and loopholes

The National Child Labor Committee pushed for the creation of a government agency focused on children’s welfare. In 1912, they succeeded, and Congress created the U.S. Children’s Bureau. Historian Molly Ladd-Taylor has examined the work of the Bureau and its first chief, Julia Lathrop. Lathrop was a graduate of Vassar College and a longtime Progressive activist, and she focused the agency’s efforts on improving infant health and better regulating child labor.

Ladd-Taylor concludes that Lathrop’s work to improve infant health was met with widespread enthusiasm while efforts to regulate child labor were often opposed by employers and struggling working-class families. The Bureau’s lobbying efforts resulted in the 1916 Keating-Owen Act, which set the minimum working age at 14 but had so many loopholes that it only applied to fewer than 10% of child workers. Worse, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the law two years later for attempting to supersede states’ rights.

When the Great Depression came in 1929, Americans were ready to take unprecedented steps to boost the economy. Many were dismayed that male breadwinners could not find jobs, which undoubtedly led to support for work restrictions on non-breadwinners. Furthermore, the Supreme Court had by then ruled that the federal government had the authority to regulate interstate commerce. The 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act prohibited children under 18 from working dangerous jobs and children under 16 from working during school hours.

The persistence of child labor

In the following decades in industrialized countries, higher wages and higher standards of living allowed most parents to leave their children in school longer. Today, child labor is most prevalent in less developed nations.

In 1989, the United Nations adopted the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which includes the right to be protected from “economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child’s education.” It also called on all nations to pass laws setting a minimum age for employment. Then in 1992, the International Labor Organization (ILO) launched a campaign to eliminate child labor. The International Program on the Elimination of Child Labor (IPEC) began with extensive country surveys of the extent and nature of child labor around the world, and then began to work within the U.N. to have all nations commit to banning the “worst forms” of child labor.

A comprehensive 2009 examination of child labor worldwide found that these efforts were somewhat successful. While there had been some 245 million children working in 2000, the ILO estimated that about 160 million children were working in 2020.

Yet, child labor persists. Some 70% of all child laborers worldwide work in agriculture, in both developed and less developed nations. The other 30% can be found working in factories, cleaning homes and engaged in informal street trade, among other things. In developed nations, children who are poor, racial minorities or unaccompanied migrants are more likely to have to work.

A recent New York Times investigation revealed that child labor is still widespread in the United States. The reporters said that finding child workers in factories producing consumer products was as simple as waiting in the parking lot during a shift change and asking young people how old they were. Many are recent immigrants who had arrived in the U.S. without guardians.

Just as with the exposés a century ago, there have been renewed calls for reform. And once again, the push to close enforcement loopholes also begs us to examine root causes and search for more holistic solutions to child labor.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.