When companies and banks began automating payroll in the 20th century, it was the first step towards the mostly cashless world we live in today. During the 1950s, bankers in Europe and North America realized that one of the best ways to persuade people to open a bank account was to pay them through the banking system. But even as direct deposits of wages into personal bank accounts became standard, it would be many years before getting money out of those accounts was just as easy.

Things shifted around 1980. The share of wages paid in cash in the U.K. fell from 58% in 1976 to 42% in 1981. In that same period, the share of Britons aged 25 to 35 with a checking account had grown from under 55% to 75%; for those aged 65 or older, that increased from less than 30% to 45%.

How wages were paid in the UK, 1976 vs 1981

For the most part, people still paid for everyday purchases in cash, which meant travelling to a bank branch to withdraw bills and coins. In the mid-20th century, cashing paychecks was a headache for banks. The queues on paydays were so long that they often extended into the street. Banks had to hire extra cashiers to deal with the rush, exacerbated because banks were closed on the weekends. Many people who were “unbanked,” with no current account or savings account of any kind, would cash their paycheck in full on payday. Others who had bank accounts simply emptied the balance upon being paid.

The solution was the robot-cashier, auto-teller, cash machine or automated teller machine — the ATM. In 1961, trailblazer Citibank tested a branch lobby device in New York City developed by Luther Simjian’s Reflectone company. Like much of Simjian’s work, the Bankograph used photographic technology to issue customers a receipt of whatever combination of check, banknote and coins was left inside. The device was of no commercial consequence, but its patents became central to further developments towards what we now know as an ATM.

Going digital

By the end of the 1960s, all large banks in the U.K., U.S. and many other countries across the world had started to implement plans to completely computerize their activities. But they didn’t yet have a way to connect retail branches with existing computer centers, or a way to give customers easy access to their money at the point of sale. Some bankers and HR professionals questioned whether direct-to-account payments were cost effective and worth the hassle.

The self-service revolution in retail banking was kickstarted with devices deployed in the U.K., Sweden, Japan and the U.S. between 1967 and 1969. Engineers had to solve significant challenges such as building electronic equipment to withstand inclement weather, developing encryption and PIN technology for authentication, and moving a flimsy banknote through a machine. Initially, these machines were clunky and difficult to operate by customers and bank staff. They were not connected to any computer network and were prone to failure.

Banks had to invest significant time and money to help customers overcome their skepticism of self-service technology. Customers were often distrustful of the devices. A common anecdote I’ve heard over many years from engineers in Mexico, South Africa and Russia is that users withdrawing money would do it by accessing the ATM three times. First using it to check their balance and print a receipt, then once again to withdraw money, and then a third time to print a second receipt with the new balance.

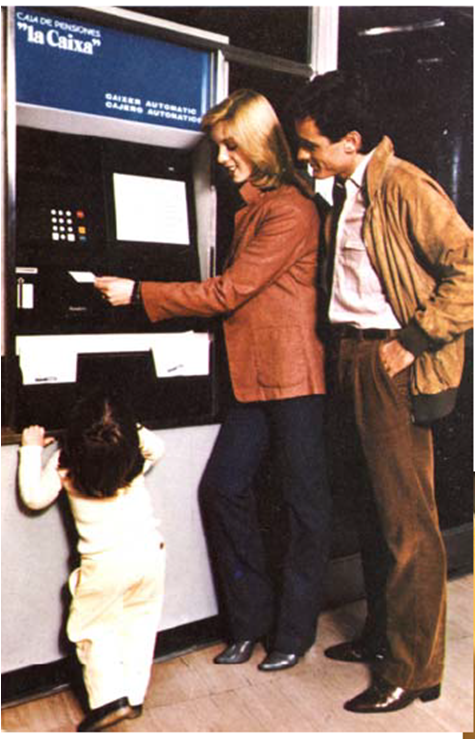

In Spain, la Caixa, now CaixaBank, took a unique approach to helping its customers. It was redesigning its branches around 1984 and hoping to convince customers to use its Fujitsu-made ATM. The bank decided that hostesses in branches would be security enough, and customers could use an ATM simply with their payment card or passbook.

The bank argued that the PIN was just another barrier in the adoption of self-service, and that it was more interested in securing adoption than in limiting potential losses. The bank later reported that losses during the no-PIN years of its ATMs had been insignificant. When customers became comfortable with self-service banking, the bank then introduced a PIN for its passbooks and plastic cards.

But in contrast to the success of the ATM, many banking innovations from this era are hardly remembered today. One short-lived method was known as the “Hinky Dinky,” named after the grocery store chain. Deployed by savings banks in the U.S. in the mid-1970s, a person operated a rudimentary terminal in a dedicated booth to help cash checks in retail spaces.

Predecessors of internet banking appeared in the U.S. and France around 1980 in the form of terminals attached to telephones. Called “home banking” in the U.S., it was demonstrated to President Jimmy Carter at the White House, but was abandoned by the mid-1980s as telephone banking took over in the U.S. In France, millions of Minitel terminals were given away to telephone subscribers to encourage using the online banking and directory tools, but the internet overshadowed the service in the 1990s.

Getting connected

Interestingly, during the 1970s, the country with the largest number of cash machines was Japan. Yet, for reasons that are unclear, its domestic manufacturers didn’t rack up significant international sales. As European and North American banks continued to invest in auto-teller technology, the interest attracted manufacturers such as IBM, Diebold, Nixdorf and NCR, who were able to connect ATMs to a larger computer network.

In Europe and Latin America, the ATM’s effectiveness in helping large banks handle cash distribution and congestion at branches was central to its success. But in the U.S., the motivation was a bit different. The biggest use for ATMs in American suburbia was capturing deposits in the form of paper checks or cash enclosed in envelopes available in a box next to the machines.

The pivotal year was 1981, when banks in the U.S., Germany and the U.K. adopted ATMs in large numbers. IBM’s 3614/3624 models sold like ice cream on a hot summer day. Big banks such as Barclays abandoned their first-generation machines for new models from NCR. In the U.S., a recession pushed more banks to prioritize automation, and savings banks began to offer current accounts and placed ATMs in areas lacking physical branches.

Their success in Europe and North America gave confidence to banks elsewhere, and they deployed thousands of ATMs in the following two decades.

Today there are as many as 3.5 million ATMs in operation worldwide. They are the backbone of cash distribution infrastructure, distributing up to 90% of banknotes in developed countries. They give people access to their paychecks regardless of whether they are in Paris, Buenos Aires, Cape Town or en route to Mount Everest, Easter Island or even on an aircraft carrier.

By easing congestion at brick-and-mortar branches, the ATM made life easier for bankers, but also for payroll professionals who wanted to encourage the uptake of direct-to-account deposits. Yet, until very recently, most mid- to low-value retail transactions happened in cash. In countries with standard pay cycles such as the Philippines, ATMs sometimes run out of bills on paydays. Could plastic payment cards hold the answer? The next installment of Looking Back will recount the advent of the debit card.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.