The creation of writing in Mesopotamia was a momentous innovation, perhaps only comparable to the invention of the internet in the modern era. Both mediums transmitted messages in a way that humans had never before experienced.

Before written communication, conveying information to another person had to take place verbally, face to face. With the invention of writing, humans created a way to inform, remember and communicate without the restrictions of time or place. The story of modern writing bloomed with the civilization of the Fertile Crescent, which was known for its expertise in the domestication of animals, agriculture, pottery and wheel making. The development of cuneiform in Mesopotamia, centered around what’s now Iraq, made possible the advances that followed in mathematics, astronomy, medicine and engineering.

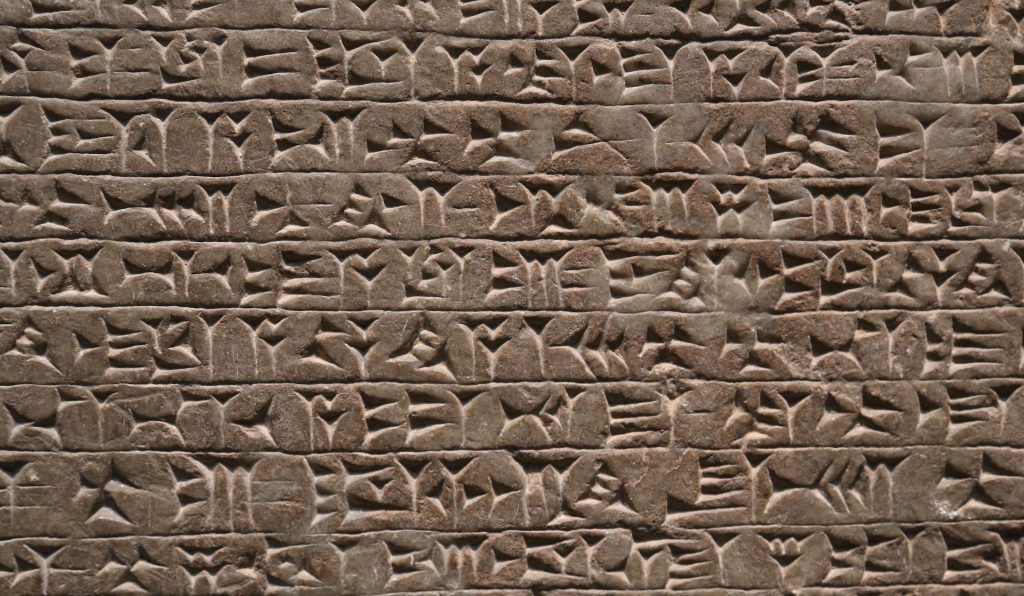

Cuneiform is recognizable by the wedge-shaped strokes created by pressing reeds into soft clay tablets, which were then hardened by heat. Thousands of cuneiform tablets have survived thousands of years, providing insight into the business world of ancient Mesopotamia: Many of the earliest examples of these ancient texts are records of workers and their wages.

Payroll in cuneiform

As specialized trades emerged in Mesopotamia, merchants and farmers needed to hire people to work for them in exchange for a fee. And as anyone in payroll knows, recordkeeping is key. Temples at this time were not only the center of religious life but also of the local economy — temples handled tax collection, lent money and invested in real estate. Many cuneiform tablets from the third millennium B.C. include daily tallies and agreements between employers and workers, detailing the obligations and rights of both parties.

In this era, a laborer received payment in kind — working in exchange for a quantity of food, clothing, housing or a share of the agricultural or industrial yield — or payment in wages — in ancient Mesopotamia this was often in barley, though silver was later used to pay wages. We know from these ancient cuneiform tablets that the wages of workers varied based on the type of work they did. Ancient law regulated land rental prices, debt interest and wages for people working in specific trades. The Code of Hammurabi from around 1750 B.C. says, for example, that a ropemaker should be paid four gerahs (a small unit of silver) per day, and a tailor five gerahs per day.

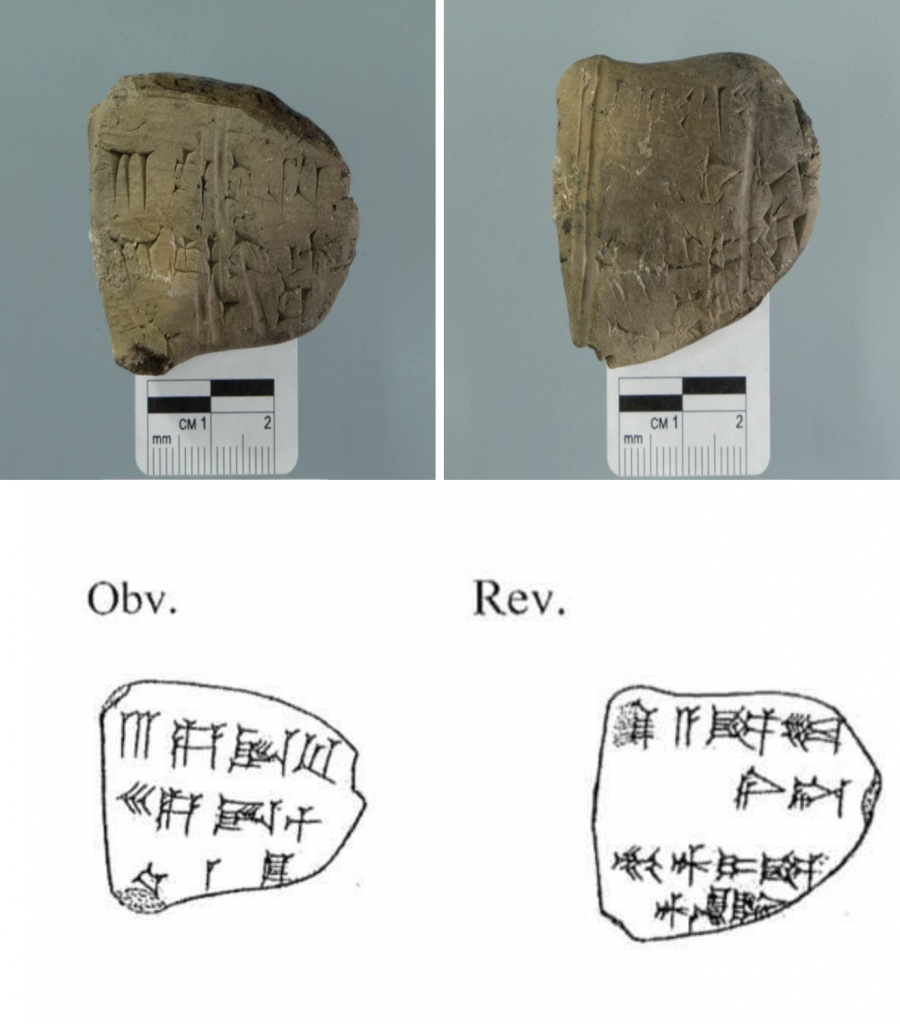

The images below of two cuneiform tablets show the development of ancient payroll. The first from the Neo-Sumerian era, circa 2100–2000 B.C., transcribed by Wafaa Hadi Zwaid. This is a receipt that details the workers’ wages for a period of work.

The text says that three gurush (free workers who were part of the temple economy) at two-thirds wages and 30 gurush workers at one-half wages were received from Abi-Tuni, the person responsible for managing workers. The date is recorded as “the year which Ibbi-Sin became king,” the first of his 24-year rule, around 2000 B.C. The seal, making the record official, is signed by a clerk under the authority of Shaat-Istar, the king’s daughter.

Ancient Sumerians were among the first users of fractions, though the Mesopotamian numerical system was based on the number 60 rather than the number 10 as we use today.

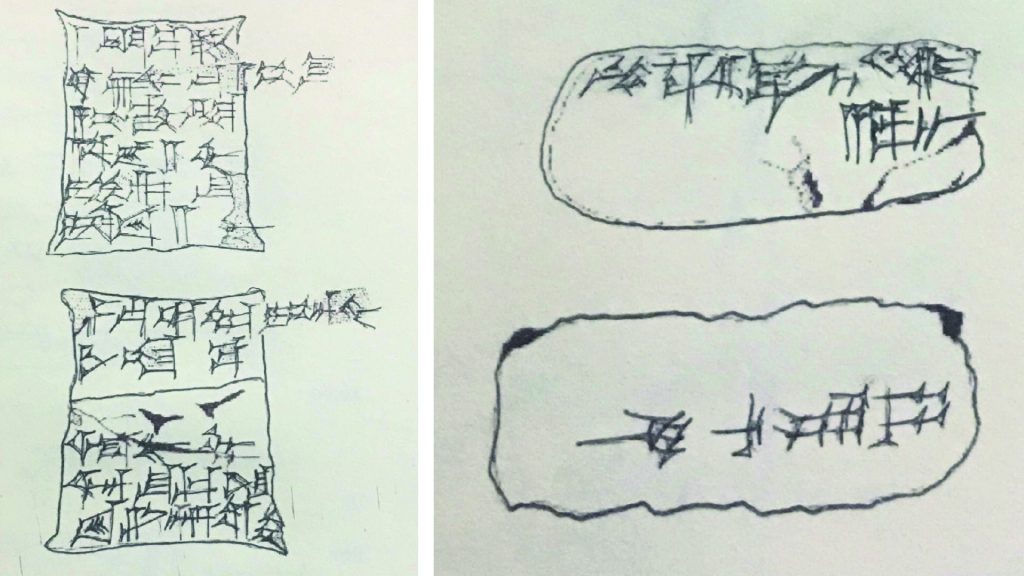

The second cuneiform tablet is from the city of Bekasi, circa 1700 B.C., during the Old Babylonian Empire. The cuneiform text, transcribed by Aram Jalal Hasan Al-Hamundi, reveals how the content and technique had developed in the meantime.

The front of the tablet says that A-pi-la-a–sin has hired Sin-magir from his father, Sa-mi-ia, for two months in exchange for a half gur of dates. (The gur was a standard unit of measurement at the time, equivalent to about 300 liters.) The back of the tablet explains that the dates would be weighed by i-bi Adad and lists the names of two witnesses to the contract. The date is written as the first day of the ninth month in the eighth year of Samsu-Iluna’s reign, and the left edge has i-bi Adad’s seal.

There are important advancements here: The stability of Mesopotamian society led to common units of measurement. King Samsu-Iluna, the son of Hammurabi, is believed to have instituted the standard Babylonian calendar during his reign, which started around 1750 B.C. Clay tablets explaining mathematics have been found dating back to this era, with explanations of algebra, quadratic equations and the Pythagorean theorem, before Pythagoras was even born.

What it all means

Let’s rewind back to 7000 B.C., when an agricultural society was developing in northern Iraq, especially in the village of Jarmo, where some of the oldest pottery in the world has been found. An ancient farmer in this area wanted to document and calculate his crop yield and keep track of his goats and sheep. So he would collect small pebbles of similar shape and size in a leather bag to keep count, adding or removing a stone when he gained an animal or lost one.

Humans started to migrate south in the fifth millennium B.C., their settlements following the fertile plains of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. As their accounting needs grew, they began to use shaped clay tokens to keep track of their crops or goods. A unit of oil was depicted by a conical piece of clay; wheat was depicted by an oval shape. Eventually the recording of these goods evolved from collecting tokens to pressing the according shape onto a clay tablet in a line.

And that led to arithmetic tables — panels drawn on clay tablets, marking the shape of a commodity and drawing small lines to denote quantity. This was a major step toward the creation of writing. The combination of glyphs and accounting allowed ancient Sumerians to document computations and content. Around 3000 B.C., recording the names of people involved in the transactions led to the development of shapes that represented sounds. The seeds for what we now know as an alphabet were planted, as this proto-writing shifted from glyphs to syllables.

About half a million cuneiform tablets have survived to this day — preserved not by importance but by chance. The ancient Mesopotamians’ diligent recordkeeping allows us in the modern era to better understand their lives, and their experimentation in recordkeeping paved the way for all of the things we do today with words and numbers. And so we can assume that Sin-magir received his half gur of dates, and if he didn’t, i-bi Adad surely heard about it.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.