Driving east from Kolkata along the historic Jessore Road — between centuries-old trees saved from felling by public resistance — the two-lane national highway is jammed with trucks, buses, cars, people and animals. They’re all making their way toward Petrapole ICP, India’s busiest Integrated Check Post (ICP), along the Bangladesh border.

The check point connects trade and commuters with Bangladesh’s Benapole Land Port — the largest land port in Asia. Petrapole ICP accounts for $2.5 billion worth of bilateral trade annually, and the Petrapole–Benapole crossing was responsible for almost 65% of the land-based trade between India and Bangladesh as of 2020.

Petrapole ICP opened in 2016 and introduced modern customs, immigration and border security to speed up the movement of cargo and people.

However, traversing the border is slow. After stopping for a local train to cross the highway at Bongaon, it takes an average of 138 hours for a truck’s shipment to cross the border once it reaches Petrapole — including 28 hours transferring cargo from Indian to Bangladeshi trucks. By comparison, trucks need less than six hours to cross borders in other regions.

Truck drivers waiting in line at Petrapole describe unpredictable transit times measured in days rather than hours. This is caused by a mismatch in handling capacity on either side of the border: Petrapole can handle up to 750 trucks per day, but Benapole can only clear 370. This makes for an uncertain commute.

Despite wait times, approximately 2.5 million people cross Petrapole-Benapole every year.

Swapan Mondal lives 30 minutes by truck from the border, in a village called Kalupur near Bongaon, India. Previously, he worked as a local truck driver for various agencies, but six months ago he began working as a heavy truck driver for an export-import company. This new job has provided him with the unique experience of regularly crossing the border.

Finding himself regularly caught in the congestion and waiting times at Petrapole-Benapole, Mondal hopes that both governments will concentrate on developing accommodation, food and restroom facilities at the port. As a driver, he is not allowed to be outside in the port area and must remain inside the truck cabin, often waiting longer than he anticipated.

Mondal’s monthly income doesn’t reflect his extended stays at the land port — he isn’t offered much additional compensation when there are delays. He is not satisfied with his monthly income as covering his living expenses on a truck driver wage can be challenging at times.

The most hectic part of his job is following the land port procedure every time during his regular arrivals and departures. Mondal believes that the process of obtaining clearance from both sides of the border could be minimized if both countries processed it jointly.

Akib is a driver who lives in Gopalnagar village, Bongaon, in India. When he first got the job transporting cargo from Petrapole to Benapole, he was thrilled to cross the border and considered it a memorable experience. However, after working as a truck driver for two years, he finds the crossing to be complicated at times.

The main issue he faces is limited communication, as there is no mobile network available for Indian SIM users in the border area. While staying in Bangladesh during a transport shift, Akib is unable to communicate with his family.

Akib earns about 25,000 INR per month (USD$300) and has to cross the border two to three times a week with various goods such as raw materials, cotton and chemicals. He is saving money for his next venture. Despite the challenges, Akib says he has made some new friends in Bangladesh who have been very helpful during his stay in the port area.

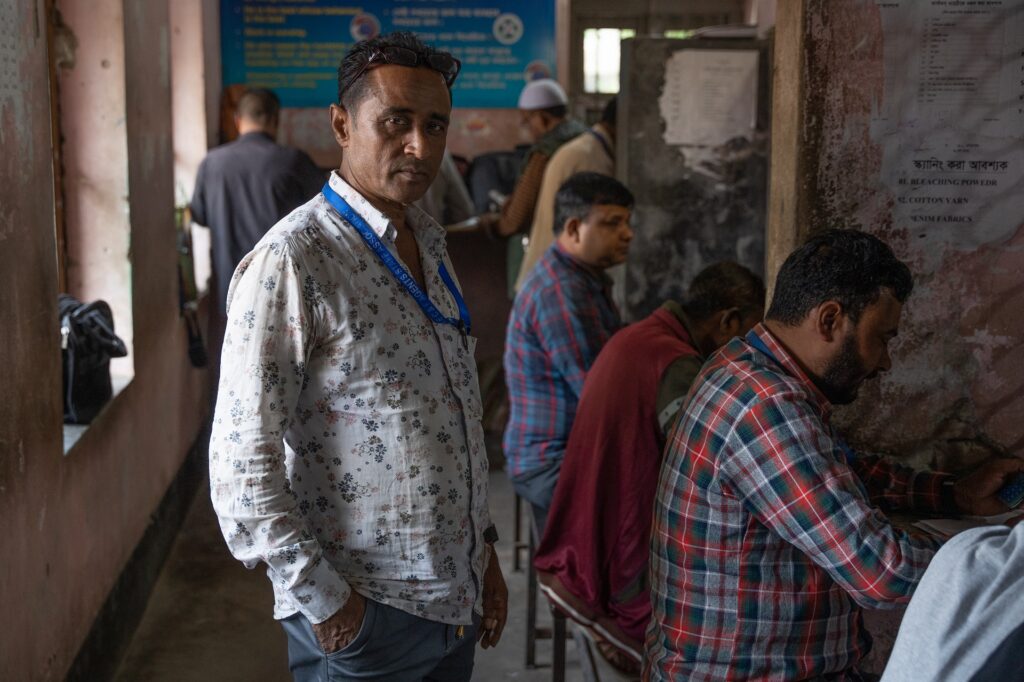

Mohammad Mojnu lives in Boro Achra village in Benapole. He is the owner of Taranga Enterprise, which is an authorized customs clearing and forwarding (C&F) agency. He began his career as a clerk at a C&F agency in 1993. After working there for five years, he established his own organization.

Monju is responsible for managing his clients’ import and export paperwork in the cargo branch, which requires him to cross the border between Benapole and Petrapole multiple times every day. Monju runs his agency with a team of 13 staff members, but he handles all customs and port-related tasks.

Initially, crossing the border and interacting with Indian people seemed like a romantic adventure when he started this job. However, over time, it has become routine. When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, the port was closed for an extended period, and he contemplated changing fields. However, he no longer feels the need to do so and is happy with his job.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.