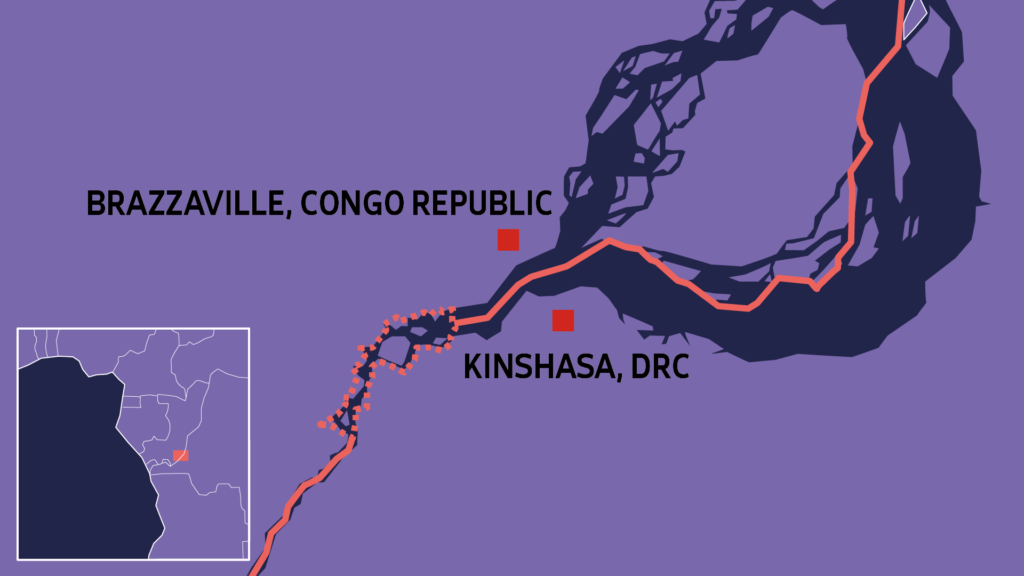

The maritime border that divides the closest capitals in the world — Brazzaville, Congo Republic, and Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo — is often called “The Beach.” Although the Congo River is just 1 km wide here, it surges with tremendous power. Instead of a bridge connecting the two banks, most travelers must board a large rusting ferry or charter a private speed boat to make the crossing. (There is also a five-minute flight between the two cities that runs twice per week.)

The cities are so poorly connected that Julien Defosse, a 47-year-old musician and event planner from France, had lived in Brazzaville for a whole year before he crossed the river and discovered the bustling metropolis of Kinshasa.

When he did, he discovered wide arteries lined with huge buildings, streets numbered in the American style, and a multitude of people — more than 16 million inhabitants, compared with Brazzaville’s 2.6 million.

Despite the river’s physical barrier, the two cities are deeply connected. “It’s not uncommon to hear it said that Kinshasa and Brazzaville are the same people, only the river separates them,” Defosse says. With just a small antenna, Kinshasa’s TV frequencies can be picked up anywhere in Brazzaville.

Defosse arrived in 2001, and after working for years as a singer and event planner in the heart of Bacongo, a popular district of Brazzaville, he decided to move his business to Kinshasa, urged to do so by a friend. At the time, he was in the middle of organizing a celebration of musician Lokua Kanza’s career.

Defosse has been crossing the banks of the Congo River regularly since 2014, spending four days in Kinshasa and three days in Brazzaville each week. Despite the complications of crossing the border, he is happy to have the opportunities both cities provide: a thriving business in Kinshasa and a tranquil home in Brazzaville.

“Thanks to this new job, I was able to buy a plot of land in Brazzaville and build my house,” Defosse says. “I could just as easily have stayed in Brazzaville and stopped with art and done something else, but the intense pace of Kinshasa has enabled me to ride the wave much faster.”

Brazzaville remains his home base, where he can breathe, calm down and revitalize. “Everything is slower, gentler and more serene in Brazzaville, unlike in Kinshasa,” he says.

His connection to both places is an important part of his identity. Defosse has different nicknames on different sides of the Congo River — he’s Kébèn in Kinshasa and Malonga in Brazzaville.

Traveling between the two is chaotic and time-consuming.

“Since I’ve been crossing the Beach regularly, not one crossing has cost me the same price,” Defosse says. “It’s easier and less complicated to cross the Beach from Brazzaville.”

But the more you cross, Defosse explains, the more everyone gets to know you, and a crossing that used to take four hours can be done in an hour if all goes well. “It can even be done in 30 minutes if you charter your own boat and have your own protocols in place on both sides. Of course, it costs more,” he adds.

Commuters used to only need an ID card to cross, and in 2014, more than 500 people crossed the maritime border each day. The number shrank following an operation known as Mbata ya Bakolo, which means “slap of the elders” — a series of expulsions of illegal foreigners carried out by the Republic of Congo, and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Today, the crossing requires a passport and a 72-hour permit or entry visa.

Defosse believes the border separating the two capitals is an obstacle to the mixing of populations.

“It wasn’t meant to be,” he says. “Two cities that could have a bridge. I dream of being able to cross the river in my car.”

Though even that would be complicated; in Kinshasa most cars are automatic, and they have their steering wheels on the right. In Brazzaville, most cars are manual — and the steering wheel is on the left.

Sometimes, Defosse considers moving his business back to Brazzaville, but he continues to be attracted to Kinshasa’s invigorating urbanity.

“It’s hard for me to know whether I could live in Brazzaville without going to Kinshasa, but I do know that I couldn’t live in Kinshasa without coming to Brazza,” he concludes.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.