It’s the early 17th century. A successful merchant from the Balkans is stopping over in the bustling Mediterranean port of Naples for a little business — trading some grain, doing some currency exchange. He hears that one of Italy’s most famous painters is taking private commissions, and he would love to go back home with his own Caravaggio to show off. He has the funds — but what’s the safest way to pay such a large amount of money in this city of ill repute? Naples is full of dark alleys, and it’s hard to conceal a heavy pouch of silver coins. He can’t just PayPal the artist — it’s the 17th century.

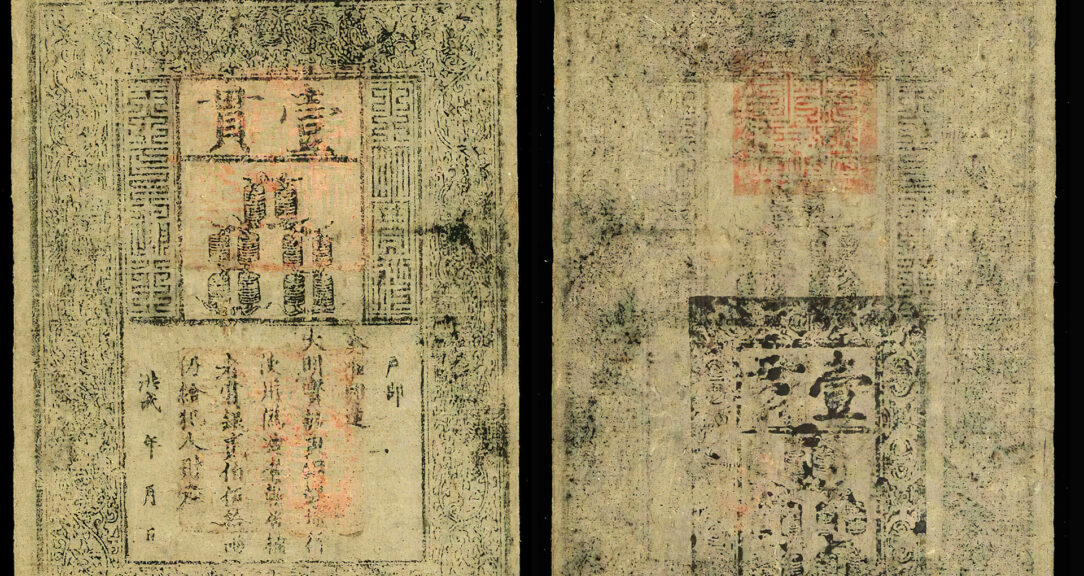

At the time, Naples was the second most populous city in Europe, with more than 300,000 residents before the 1656 plague claimed half of them. In 1750, it ranked third after London and Paris, according to historians. Since it was a bustling port city with lots of foreign trade, bankers created financial solutions to ease transactions for its inhabitants and visitors. Though Naples banks didn’t invent cashier’s checks — the Dutch claim that honor — they did make a business of it. In this era of electronic wire transfers and credit cards, it’s easy to forget the long epoch of cashier’s checks. Unlike personal checks, cashier’s checks are guaranteed by a bank. As a 17th century merchant, even if you didn’t have an account with a local bank in Naples, you could deposit your money there and get a “fede di credito” that you could give to anyone you were doing business with.

What was special about these fedi di credito is that some would pass on from one person to another — like transferable checks, or third-party checks, which are not so common or safe nowadays. Whenever they passed from one person to another, records were created in the issuing bank. Today, an archive of the Banco di Napoli, one of the world’s first banks, has preserved nearly 400 years’ worth of these transactions.

“Through the bookkeeping of the Banco di Napoli, we can piece together the history of the city,” says Amedeo Lepore, professor of economic history at the University of Campania Luigi Vanvitelli and at Luiss University in Rome.

Naples is a city confined by its geography, with the sea on one side and Mt. Vesuvius on the other. In the 1600s, the city had already started to grow vertically, boasting four-story buildings that would have been as impressive as today’s skyscrapers. Over the years, the banks’ collection of fedi di credito grew alongside the city’s business. To better preserve the records, bookkeepers copied the information from the fede di credito in books, sorting them by the names of those who paid, the amounts they paid and the reason for the payment.

It’s like a huge Excel file of 400 years of history of Southern Italy.

Andrea Zappulli, ilCartastorie

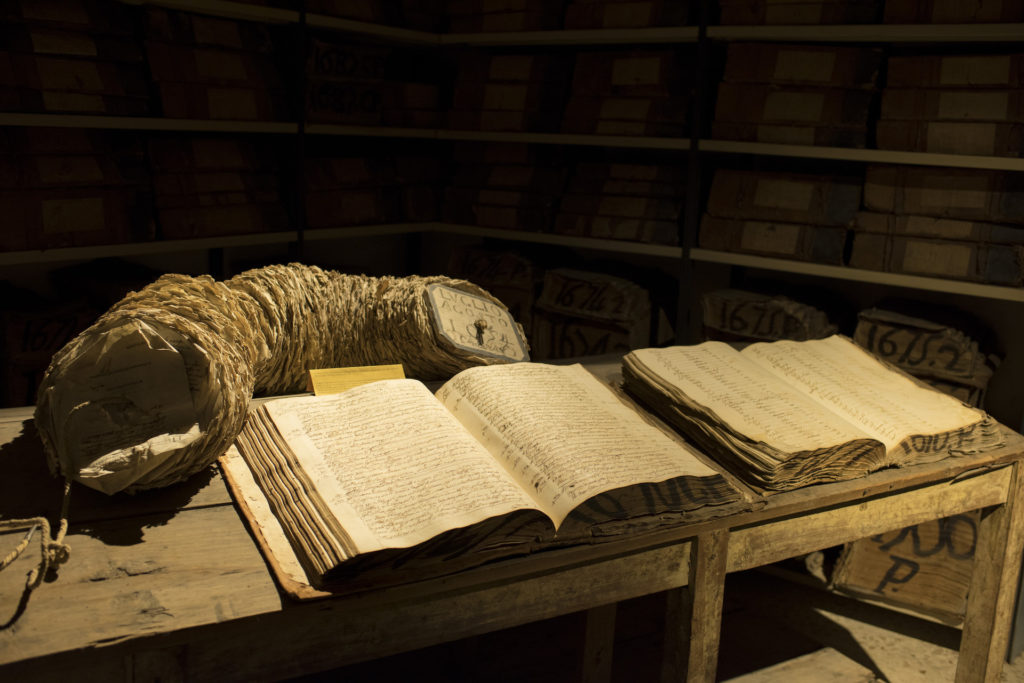

Someone had the idea to pile up the fede di credito as if they were pieces of meat in a skewer — this archival technique is called a “filza.” The original twist from the Banco di Napoli bookkeepers was hanging the 1.5-meter filze from the high ceilings of the bank in order to make the most of the space they had. The system was used until the early 19th century.

The Banco di Napoli Historical Archives have 10 filze that are still intact. Most have been opened up in order to study the contents of the documents. There are no gaps in the records: Starting in the mid-1500s all the way to the 1960s, the fedi di credito tell Naples’ stories, year after year.

“It’s like a huge Excel file of 400 years of history of Southern Italy,” says Andrea Zappulli of ilCartastorie, the museum of the National Archives of the Banco di Napoli.

The Banco di Napoli dates back to charitable institutions that arose throughout Italy, including Naples, between the 16th and 17th century, in particular the mounts of piety. Operating like an institutional pawnbroker, the mount of piety was founded in 1539 and allowed the city’s wealthy to lend money without interest. (Some scholars date the bank’s origin back to an even earlier charitable institution founded in 1463.) The Banco di Napoli eventually became a subsidiary of Intesa Sanpaolo group before being fully absorbed in 2018, meaning it no longer exists.

But the bank’s archives, stored on about 80 kilometers worth of shelving spread across two different buildings in Naples, are very much alive. In addition to the fedi di credito that make up the filze, it holds documents on the structure and evolution of banking and credit institutions, as well as business contracts with other European nations.

“It is one of the most important financial archives in the world,” says Lepore.

The currency at the time was the ducat. Ducati were gold or silver coins that were used for trade in Europe from the late Middle Ages on. Surviving fedi di credito give details of hospital bills, provide a record of payments for fireworks (20 ducati) and musicians for celebrations, and offer details of life in prison. One priest paid 20 ducati for the comforts he wanted in prison (a bed, a lamp and a door), and a lawyer received 600 ducati for defending those who couldn’t afford legal costs.

There are also the exact details of how a merchant from modern-day Dubrovnik, Nicolò Radolovich, paid the master painter Caravaggio an advance of 200 ducati for an altarpiece in 1606. (A laborer might have earned a few ducati a month, so this was no small sum.) Caravaggio was at the height of his fame — his paintings depicted realistic scenes of life and death with key figures highlighted with bold light and dark colors.

The fede di credito in this case also served as a commissioning contract, describing precisely what the painting should look like: “painting that must be finished and delivered before the end of next December, with a height of 13 ⅔ palms and width of 8 ½ palms with the image of the Madonna with the child in her arms surrounded by choirs of Angels and below Saint Dominic, and Saint Francis in the middle, with Saint Nicolas on his right and Saint Vitus on his left.” The record of the money transfer exists to this day, but unfortunately, the painting was lost.

Much of the Banco di Napoli’s archives are accessible online and in real life thanks to ilCartastorie, which was inaugurated in 2016 to tell the hidden stories in the archives with performances, texts and videos.

We don’t know if Radolovich ever received the Caravaggio painting he ordered in 1606, but 400 years later, the museum commissioned a tableau vivant play to give a sense of what the painting might have been like. Against the background of huge leather binders with dramatic lighting reminiscent of Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro technique, actors in historical clothes rendered several possible versions of the painting — an event followed closely by the media and artists in the city.

“We don’t want to show documents; we want to tell the stories contained inside the documents,” Zappulli says. “Because, unlike art museums, this museum tells the stories of those who are visiting: of their ancestors, the places they live, the roads they walk on.”

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.