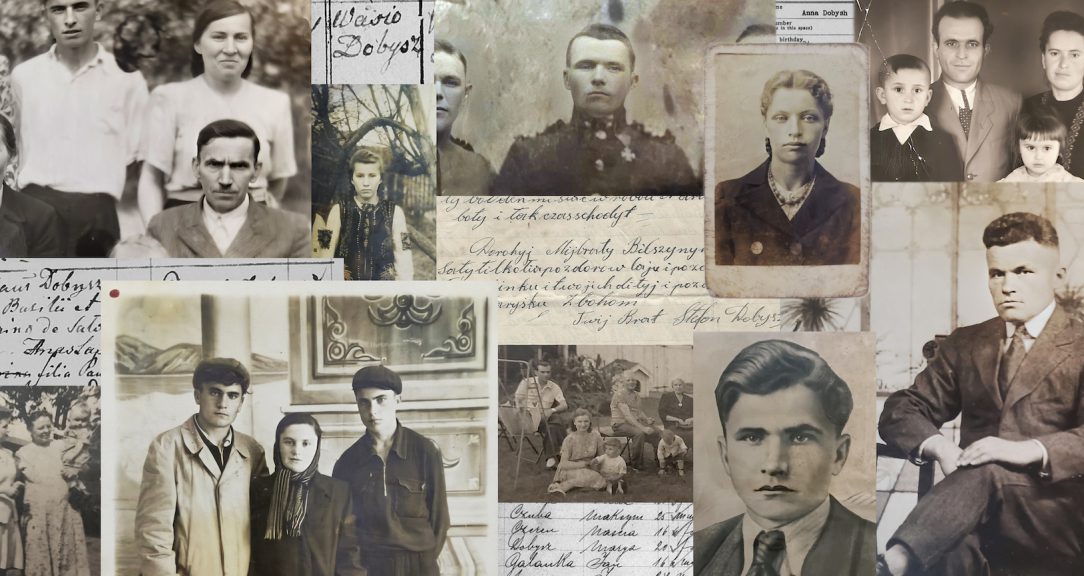

When Jinkie Alhambra first set foot in Hong Kong, she was just 18 years old and very much against the idea of working in a foreign land. Her mother, a domestic worker who has by that time been working as one for nine years already, asked her to work for her employer too.

“I was just 18, that was in 1989,” she says. “I just got out of high school, I was in my first semester of college. I didn’t want to go; I wanted to study.”

But during that time, the family needed extra funds because her parents bought a bigger house and had to pay for her two younger siblings’ education.

This left a mark on her and largely influenced her mindset when she became a mother herself and continued being an overseas Filipino worker, commonly called an OFW.

“My children’s education will always be my priority. I didn’t buy a house until my sons have graduated from college already. If you channeled your resources to two things at the same time, one will always be sacrificed or neglected,” she says.

“That’s what happened to me. That was a wrong move from my mom. If they didn’t buy another house, I wouldn’t have to go. At that time, I don’t want to come here and work.”

So Alhambra and her husband — who started out in Dubai as a waiter and worked his way up to a chef — focused on saving and spent money mostly on the studies of their children, paying for private schools.

About 2.2 million Filipinos work abroad, sending money home to 12% of all households in the Philippines. The remittances from these “modern-day heroes” have been the backbone of the Philippine economy since the 1980s, accounting for as much as 11% of the gross domestic product.

The pandemic, however, has seen the repatriation of at least 153,000 OFWs in 2020 as the global economy shrunk and mass layoffs happened in many parts of the world, forcing them to come home. While remittances were up by 2.5% in October 2020 from the year before, they’re projected to be flat this year as more job cuts are expected.

The dream of education

Overseas work has a long history in the Philippines, which is made up of more than 7,600 islands. But during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos, OFWs became vitally important to relieve high unemployment and bringing in foreign currency. In 1982, Executive Order 857 required OFWs to send as much as 70% of their salary home via banks managed by the government. If workers didn’t comply, they would be considered ineligible to work abroad. Amid outcry from migrant workers, the policy was eventually repealed in 1985. But the trend of overseas work remains part of Filipino life.

Education is one of the major priorities for OFWs. According to a 2019 report on remittances in Asia from UniTeller, aside from being spent for basic needs, 13% of the remittances sent by Filipino migrant workers go to expenses related to education.

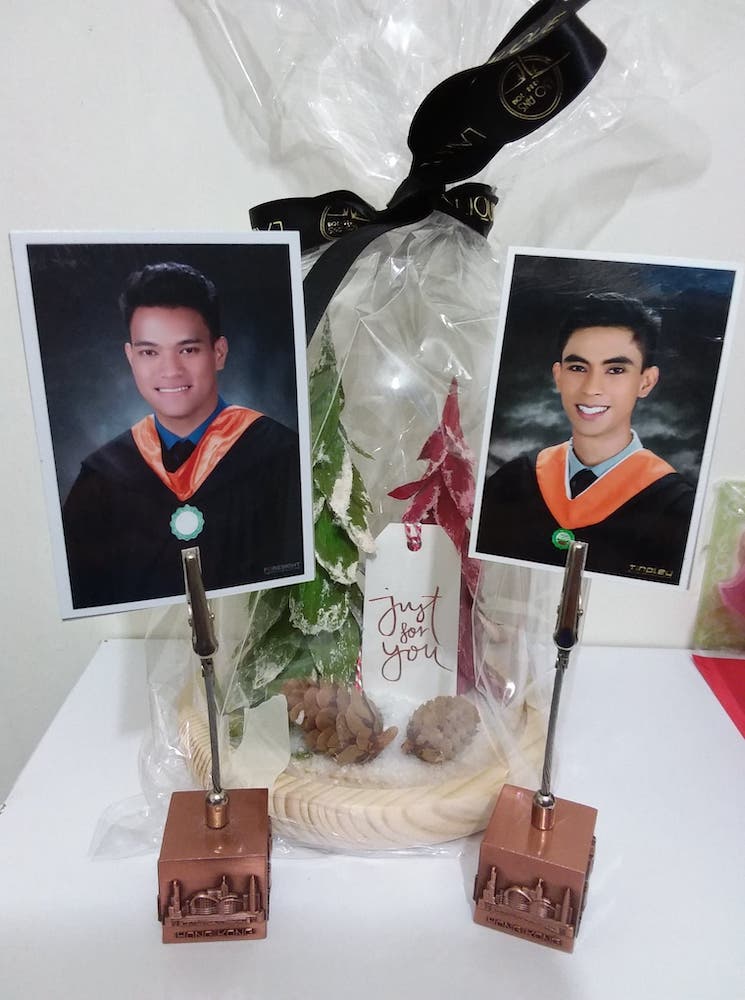

“It helps us to pay our bills, shop for groceries and provide allowances for school,” says Jeremy, Alhambra’s eldest son. Now 26 years old, he lives in their house in the southern province of Cavite and helps pay for the monthly mortgage.

Alhambra’s employer — relatives of the same family whom she and her mother worked for when she was 18 — gives her salary in cash or deposits it to her bank account. When she was a child, she remembers her mother sending remittances via banks or agents, who would deliver the money to their home in person.

As a child, I cried myself to sleep the first time my mom left us. That was 2004, and the weight of the loneliness is almost all the same every time she leaves.

Though one time the agent duped them and made off with the money. Digital options for sending remittances are safer, and Alhambra now uses a money transfer app. She is charged 15 Hong Kong dollars (about $2) per transfer with one month free where she can send remittances without having to pay the cable charge.

While the remittances secured Jeremy and his brother superlative educations, he said that he misses their mother every time she has to leave.

“As a child, I cried myself to sleep the first time my mom left us,” he says. “That was 2004, and the weight of the loneliness is almost all the same every time she leaves.”

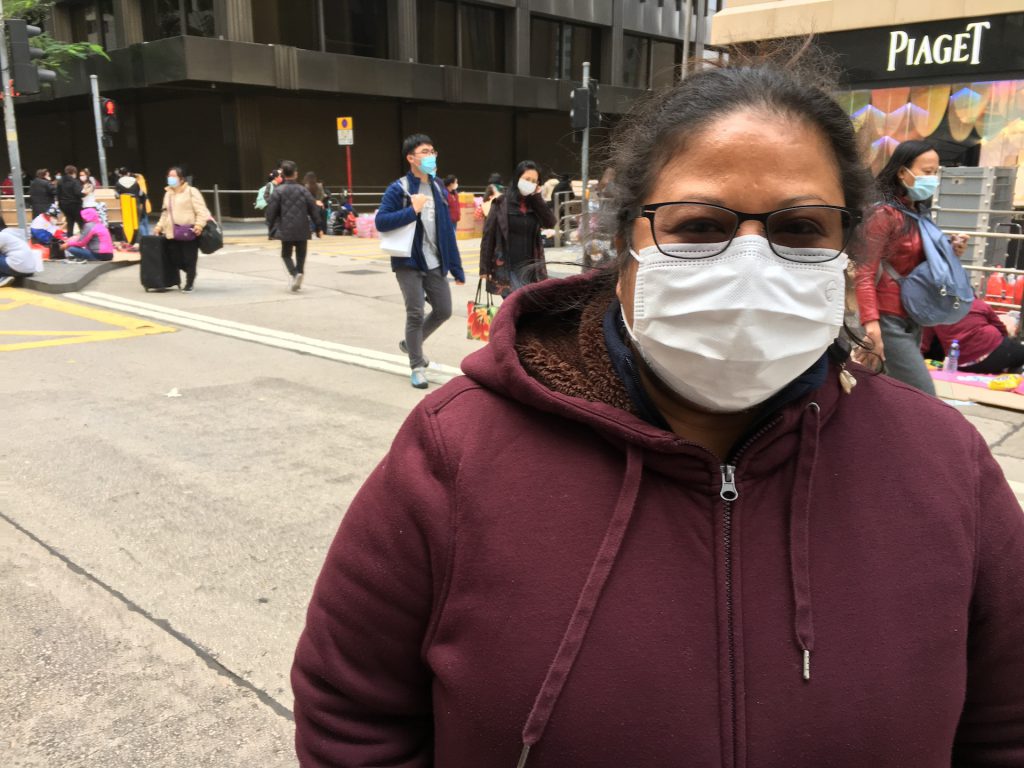

Remittances are also often used to support aging parents, as in the case of Dolores Balladares Palaez, another Filipina who has worked as a domestic worker for 20 years in Hong Kong.

She flew to the city in 1995 at age 25 after failing to find a decent-paying job even with a business administration degree. She looked for opportunities in South Korea and Hong Kong, and it was the latter that opened doors for her, as there were many opportunities in Hong Kong recruiting overseas workers.

“When I went here, the monthly wage then was only HKD 3,860,” Palaez says, about $500. “I would send 30% to 40% of it to my mother.” That money was enough for her mom’s food, medical check-ups and medicines.

The game-changing pandemic

When Covid-19 came into the picture, remittances also became a critical source of funds for some families to afford the most basic of needs. This was the case for Marjorie Cantre, a 29-year-old government employee whose older sister, Jovie, is also a domestic worker.

“My older sister is not really obligated to send money to us regularly because we have jobs now; she’ll send us money only when we asked her to,” Marjorie Cantre says. “But during the pandemic, she had to consistently send us remittances because our father lost his job.”

Cantre’s father worked as a foreman in a construction project. During the pandemic while the Philippines was on lockdown for three months, the project was halted. She said when their father lost his job, Jovie sent them 6,000 to 10,000 Philippine pesos monthly ($125 to $208), about a third of what she earns monthly in Hong Kong.

The Philippines had tallied more than 500,000 cases of Covid-19 and more than 10,000 deaths by the start of February 2021, the second-hardest-hit country in Asia after Indonesia.

“How important are the remittances? They’re quite important. We use it for our basic needs and to pay the bills. Somehow, it eases our financial worries,” the single parent of two said.

Improving financial management

Marjorie’s older sister, 37-year-old Jovie Cantre, is affable and has the brightest of personalities. But she knows how to put her foot down when needed, a trait which manifests itself when it comes to helping out her family.

“Aside from Marjorie, I also gave my youngest sister — she’s 27 — capital to start a small business in the Philippines,” she says. “Since she’s having a hard time finding work, she said she’ll try to manage her own business. I gave her PHP 10,000.”

“She said it’s a debt she’ll pay, but we know it wouldn’t really work that way. I wanted to help her out, but I told her to manage the business well,” she says. “If they misuse or squander this capital, they wouldn’t be able to ask for funds from me again.”

Jovie Cantre learned how critical it was to manage finances wisely after her salary in her first year in Hong Kong went to helping out her aunt, who also worked as a domestic worker there, to pay off the latter’s huge debt. Loan repayments, along with bills, unfortunately take a bigger chunk of allocation of the remittances sent by OFWs at 25%, the report from Uniteller said.

“I remember that when my phone will ring, I will already be trembling in fear, as it may be the credit collector,” she says.

It was tough for Jovie Cantre, as she was also being underpaid then — her salary was HKD 2,000, way below the minimum wage of HKD 3,580 during that time in 2009. She was able to sue her employer and get the full salary they owed her with the help of a group composed of foreign domestic workers fighting for migrant labor rights.

We’re fortunate enough that our employers have stable jobs. But one can never be sure, so we have to make sure whatever we earn is spent wisely.

Palaez, the youngest in a family of nine, she said that whenever she sends money to her mother, the rest of their brood will know about it and her mother will give them money, too.

“My mom is a one-day millionaire. She doesn’t really set aside money for future use,” she said while spending another day off at Central, the de facto place of recreation and relaxation for many of the Filipino domestic workers on Sundays.

Now 51 and with a 7-year-old child on her own, Pelaez said she still sends money to her 87-year-old mother, but she sets aside the majority of what she and her husband earn for her son’s education. “We’re fortunate enough that our employers have stable jobs, so we weren’t as affected by the pandemic,” she says. “But one can never be sure, so we have to make sure whatever we earn is spent wisely.”

To stay or to go

When Alhambra learned that she contracted Covid-19 in March 2020, she was more surprised than anything. The Filipina domestic worker in Hong Kong takes up Muay Thai classes and had not been sick in ages.

“No one is really immune from it,” she said. Her employer, who just got back home from a trip to India and then went to Canada, tested positive for the virus before she did.

When Alhambra told her family about it, they wanted her to go home to the Philippines. Her two sons, after all, have jobs already, and so does her husband. They were making more than enough there, so much so that she need not send back most of her HKD 4,630 monthly salary.

“I only send back 50% of my salary now, to pay for what they need in the house, but the utilities, they’re the ones already paying for it,” she says. “My sons were even telling me, ‘Ma, you need not send money back home anymore.”

After 17 years of working overseas in Hong Kong, Singapore, the U.S. and Dubai, Alhambra considered enjoying the fruit of all that hard work.

She ended up staying in Hong Kong after she got well. “I will just finish my contract here,” she says. “Then I will go home by the end of 2021. I have entrepreneurial spirit, so I will try other ways to earn money in the Philippines.”

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.