The pandemic has increased anxiety around the globe. We’ve faced losses of loved ones, uncertain futures and major changes to our routines. But many pandemic worries are caused by uncertainty about work and income.

Percentage of people by region who reported being concerned about their financial and/or job security during the pandemic

Financial insecurity has become a more pressing issue since the start of the pandemic. According to the ADP Research Institute, 69% of workers say they have been paid late at some point, an increase from 60% before the pandemic. That creates significant stress as well as potentially costly consequences in the form of late payment fees, overdraft charges or loans taken out to get by.

The World Bank reported that in 2020, the number of people living in extreme poverty (defined as living on less than $1.90 a day) rose for the first time in 20 years as the pandemic pushed an additional 100 million people into that category.

And the number of people living below the poverty line also grew. In the United States, the number of people living below the poverty line ($13,171 in annual income for a single person or $26,496 for a family of four) rose to 37.2 million in 2020, almost 10% more than in 2019. In Latin America, the number of people living in poverty also rose by 11.7% from 2019 to 2020, to 209 million people, a third of the region’s population. In Europe, the lowest quintile of earners saw the biggest drop in income: -10% from 2019 to 2020.

Theories of need

Financial stress and income insecurity are not only causing daily anguish, but they also dampen people’s future potential.

In the mid-20th century, a new generation of social psychologists started studying the conditions that help people thrive. They asked questions like: At a fundamental level, what does self-actualization look like, and what does it require of us? What are the conditions that promote psychological safety, and how might they be implemented, both individually and collectively?

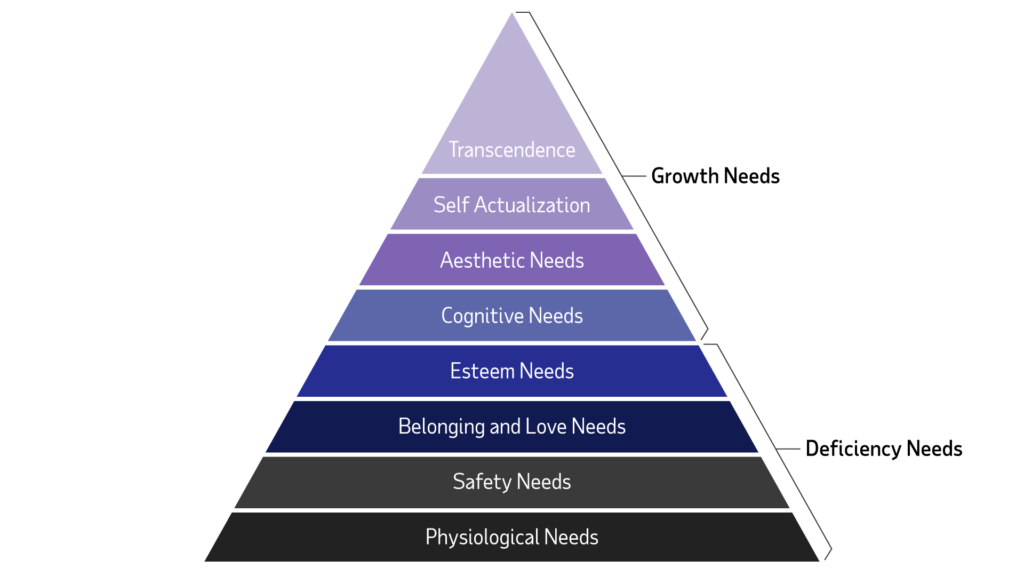

In 1943, psychologist Abraham Maslow introduced his concept of the hierarchy of needs, an idea that has since shaped sociological research, business and management practices, and political thought. It is a classification of human needs that must be met in order for individuals to reach their full potential.

At the base of the pyramid are so-called “deficiency needs,” our most essential physiological needs: food, water, shelter, rest and physical health. A person cannot function fully without them. Then comes safety and the need for basic security, followed by belonging and love, then a sense of esteem. All four of the foundational categories must be fulfilled before higher-level “growth needs” can be met: cognitive ability, aesthetic needs, self-actualization and, finally, transcendence.

If our basic needs aren’t met, Maslow theorized, our behavior will reflect this deprivation. In modern terms, this is a person with low emotional bandwidth.

The ability to reach a place of emotional security depends on access to basic financial security. Living in poverty has real, demonstrated emotional consequences. Studies have found that high levels of financial precarity can predict behavior and lead to further instability. Simply put, it’s incredibly stressful to live in poverty, and that experience of stress makes financial precarity even harder to climb out of.

More recent studies have shown that the stress associated with poverty can significantly weaken cognitive functioning. In a 2017 study, researchers found that resource scarcity causes people to be less able to focus on tasks, and also that attention trade-offs can play a role in how the brain encodes memories.

Poverty imposes a cognitive tax.

The health effects of poverty are particularly pronounced in children. “Poverty imposes a cognitive tax,” World Bank researchers wrote in a 2015 report. Impaired cognitive development, including decreased ability to cope with stress and make decisions, has been observed in children growing up in high-stress environments such as those caused by poverty.

Making budgeting decisions with little, for example, makes people so singularly focused on the task in front of them that they often overlook information that may relieve financial stress in the long term. The ability to take the future into account is a financial privilege in and of itself; when basic, short-term needs are beyond reach, it becomes more difficult — often impossible — to plan ahead.

How do we move forward?

Relieving financial stress is helpful for people at all levels of income. Experiments with Universal Basic Income are increasing. Many governments used direct cash benefits to support citizens through furloughs or job losses and to stimulate spending. The way economists think about minimum wage has changed in light of real-world experiments that show wage increases do not reduce job rates.

Payroll teams can help reduce stress by ensuring accurate, timely wages are delivered to all employees. EY estimates about $1 trillion is stashed in employer payroll accounts on any given day, which it says is an opportunity.

If policymakers consider the way scarcity-induced stress impacts a person’s decision making, efforts to lift people out of the cycle of poverty could make a greater impact.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.