The international border is a relatively new concept. Today, the total length of the world’s borders (256,613 km) is the equivalent to traveling 15.5 times around the Earth’s circumference — but more than half of these boundaries were only defined in the 20th century, and less than 1% were created before 1500.

Yet national boundaries are often thought of as ancient and immutable. This idea is reinforced by contemporary policymaking in response to successive forced migration or displacement events — both climate- and conflict-induced — that encourage greater investment in securitized infrastructure along border lines. For example, Frontex, the E.U. border and coast guard agency, will see its budget rise from €280 million in 2017 to €900 million in 2027.

As a result, the world has seen a remarkable increase in walls, barriers and fences. At the end of the Cold War, the world had just 12 border walls. Today that figure has risen to 74, with the majority constructed since the beginning of the 2000s. Together, they extend for more than 32,000 km — 80% of the Earth’s circumference.

Number of border walls globally, 1950-2020

Despite this momentous trend towards fortification, borders remain a place of economic, social and cultural exchange for millions of workers around the world.

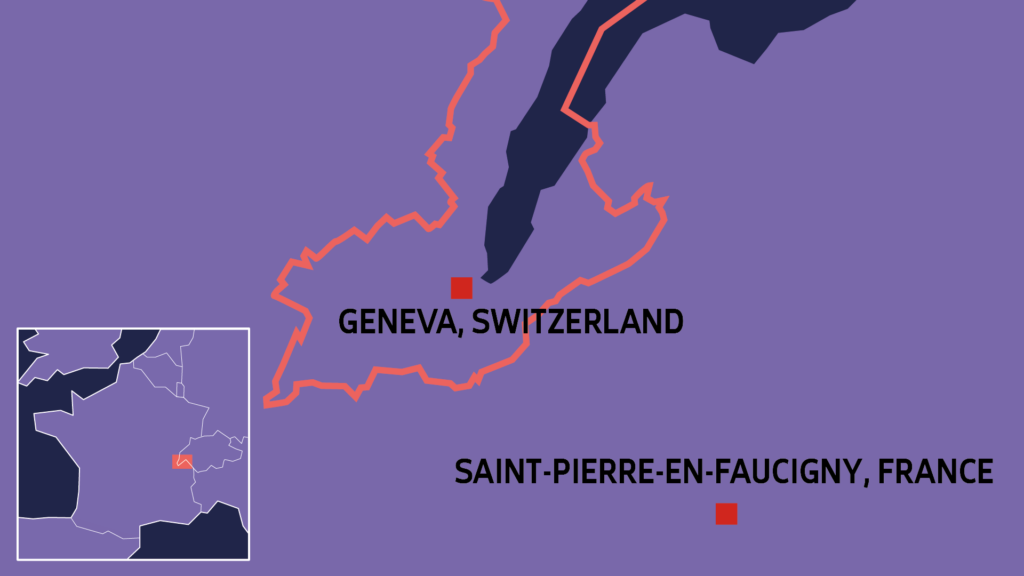

In Europe, within the boundaries of Schengen and the EEA (European Economic Area), E.U. workers are free to cross borders without the need for additional legal status, thanks to the E.U.’s foundational free movement of labor principle.

Neighboring member states often agree to special rules for these workers through bilateral double taxation conventions or, in the case of the Nordic countries (Denmark, the Faroe Islands, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden), a multilateral income tax treaty.

In the E.U. in 2020, 2 million employed people aged 15-64 years (1% of all employed) commuted from their region of residence to a different country for work. The highest rate of cross-border commuting in 2020 was recorded in Slovakia, where 5% of employed people commuted to a different country for work, followed by Croatia, Estonia and Luxembourg (3% each).

Outside of the E.U., however, the free movement of labor is not always so simple. On the U.S.-Mexico border, for example, where there are an estimated 372 million annual legal crossings across 48 points of entry, commuters who can afford to pay an annual premium, as well as undergo extensive background checks and interviews, are able to reduce their border wait times from an average of 90 minutes to just 15. Those who can’t afford to, however, must factor long traffic queues into their commutes.

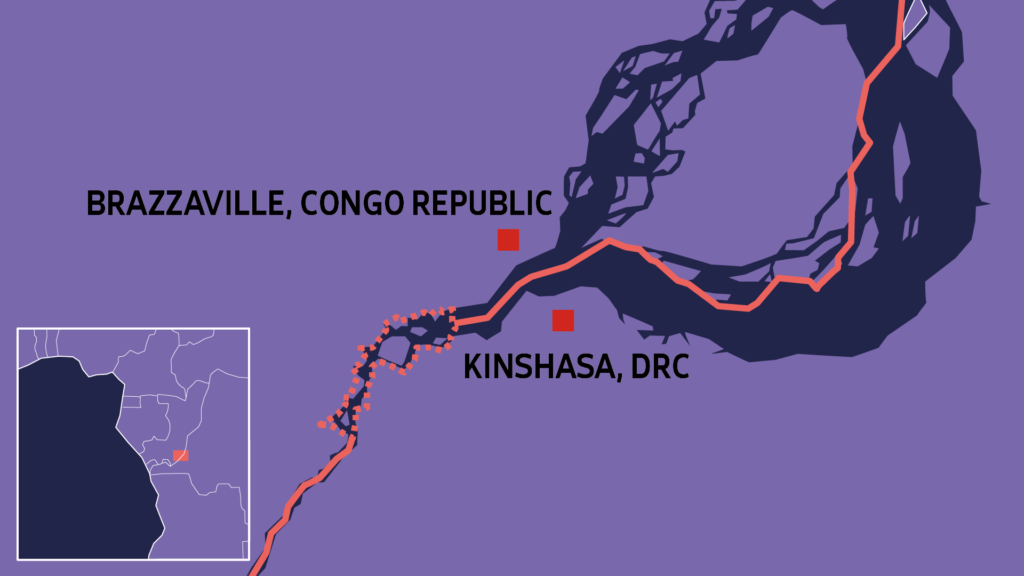

Borders — particularly those arbitrarily demarcated by colonialism — disrupt communities and informal economies. In the East African Community region of Africa, for example, the busiest cross-border commutes occur along the Uganda-Kenya border at Busia and Malaba. Here, in Busia County, there are over 60 formal and informal crossing points, and approximately 23,000 people cross per day. The borderland economy is highly dependent on informal cross-border trade: Over 60% of border crossers are self-employed, and return across the border within one day.

The complication of paperwork, premiums and border wait times disrupt the flow of business. The EY 2023 Mobility Reimagined Survey found that 88% of employers believe mobility can help address global talent shortages, yet only 47% of businesses currently have a consistent mobility policy that addresses increasing demands for flexible and agile working.

Despite the challenges, economic opportunities continue to draw people across border lines. The ReThink Quarterly enlisted journalists to find cross-border commuters from six regions of the world to learn more about their binational work journeys and the impact it has on their lives.

Click on the regions below to find out more.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.