Though we still speak of paychecks to this day, very few people actually touch paper checks anymore. The ADP Research Institute in 2019 found that more than 80% of workers globally are paid via direct deposit.

How people get paid worldwide

Paper paychecks, especially in the United States, were an innovation in digitization that helped fuel the economic boom after World War II. But how did the printed paycheck take off so rapidly, only to fall out of fashion again within a few decades?

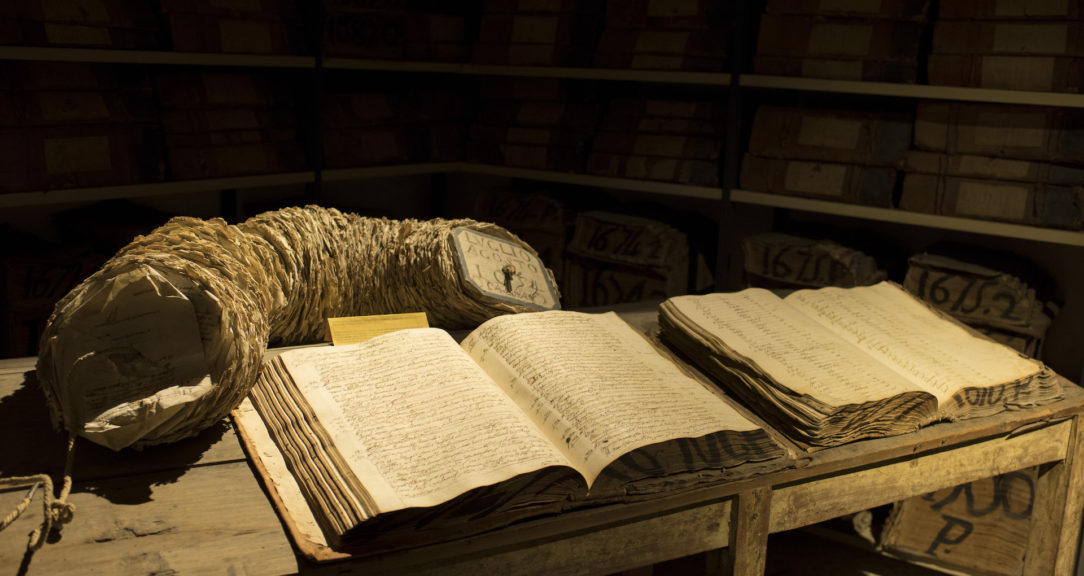

The origins of the check

In the Middle Ages, early forms of money emerged as documents began to supplement the use of precious metals, pearls and gems in international trade in Europe and the Middle East. These promissory notes known as “bills of exchange” gave rise to personal checks shortly before the Industrial Revolution. Legislation enacted in the 1830s in England stated that the bank, not the customer, was liable for cashing a check with a false signature. This was an important step to give paper checks more credibility.

A number of banking reforms made the check a popular means of payment. By the mid-19th century, most commercial and industrial transactions in England were settled by checks rather than bullion, bills of exchange or notes. The popularity of the paper check was also evident in the U.S. and in France, where some thought that personal checks could be a solution for “the big problem of small change,” thus representing the first proposition for a cashless economy.

At this time, workers received wage packets, or envelopes with notes and coins. In the mid-1860s in England and the late 1870s in the U.S., the term “paycheck” was adopted to refer to a printed order to a bank to pay a stated sum from the employer’s account.

Between 1900 and 1920, wage packets in the U.S. and Germany began to include a pay slip alongside the actual cash. This led to the emergence of the “pay envelope,” or a brown flat container stuffed with cash and a pay slip in the U.S. and U.K., or a “pay stripe” in Germany, a printed receipt.

In the meantime, Austria began to develop a pioneering system for direct-to-account payment through postal giro systems. During the 1920s, an increasing number of people in Europe — mainly managers and white-collar employees who received a fixed wage or salary — were paid by direct transfer to bank accounts.

Processing and clearing paper checks required a lot of work, especially as U.S. banks were operating mostly only locally until the 1980s. Supplanting a system of local clearinghouses, the Federal Reserve standardized the United States’ check collection system in 1913, reducing the amount of time it took checks to clear. The expansion of branch banking in the U.S. after World War I led to increased use of checks. But in response to the Great Depression, President Herbert Hoover imposed a 2-cent tax on each check with the Revenue Act of 1932. Some scholars believe this revenue-creating attempt actually helped make the economic situation in the United States worse, and it led to a widespread return to wages paid in cash.

The automated paycheck

In years that followed World War II, banks on both sides of the Atlantic began to automate, with the payroll function leading the way. Computers could be used to calculate wages and to print the associated payslips distributed to employees on pay day — but these wages were then paid in cash.

In countries including Mexico and the U.K., the law prohibited employers from paying salaries with anything other than cash, because some companies had abused their power via non-cash payments, such as in vouchers good only at the company store. Before wages could be paid via check or direct deposit, the laws had to be amended.

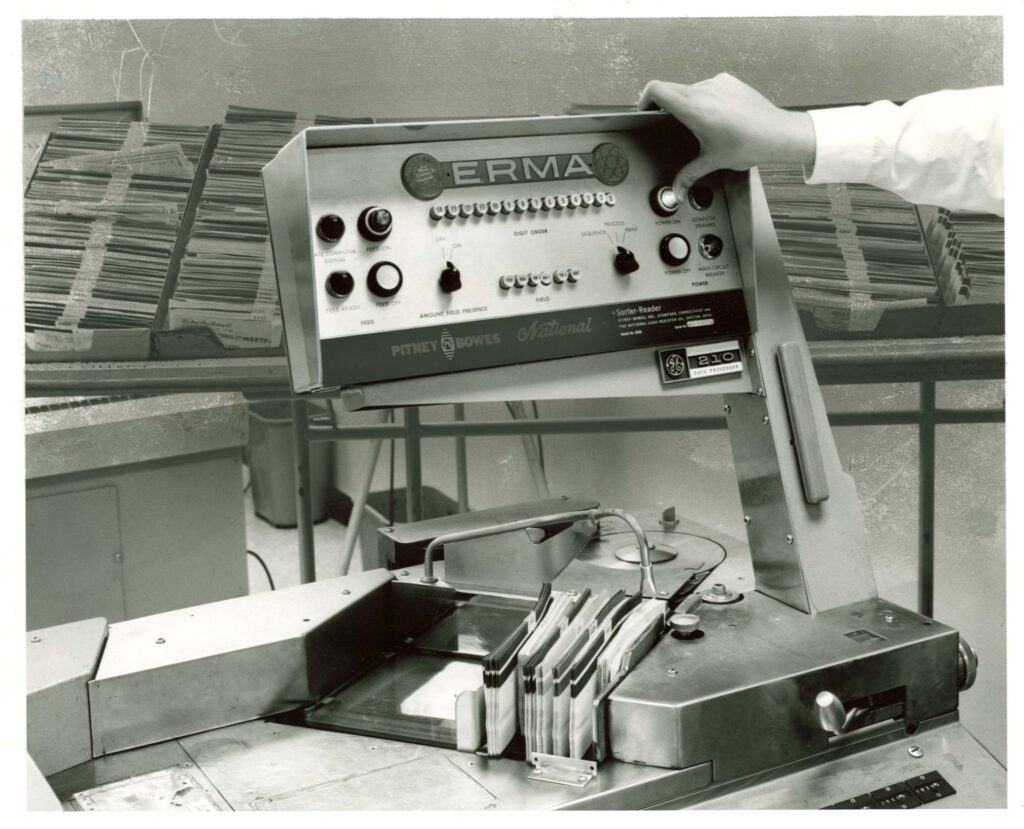

But in the United States, paychecks gained traction as more middle-class Americans opened bank accounts. In 1951, the collaboration between Bank of America and the Stanford Research Institute in California led to the development of Magnetic Ink Character Recognition (MICR), a technique for making printed bank routing information machine-readable. The genius of the system was that the characters could be read by humans and also by machines using magnetic or optical sensors.

The American Bankers Association officially adopted the E-13B MICR font as the standard for negotiable documents in 1956, and the U.K., Canada and Australia followed suit. In France, Groupe Bull developed the rival MICR font CMC-7 in 1957, which became the standard in Europe and Argentina. Though MICR was developed to speed up handling of paper checks, it was soon adopted for other applications such as sales vouchers for credit cards and airline reservation tickets, and is still used today.

The introduction of MICR was essential for automating the clearing of paper, and it cemented the use of checks in the increasingly affluent and consumer-driven American society. An experienced bookkeeper could process 245 checks per hour at the time; Bank of America’s ERMA system eventually could read 10 checks per second — 36,000 per hour.

Europe was an early adopter of direct-to-account payment of wages, mostly bypassing paper paychecks. From the 1950s in Sweden, workers were encouraged by banks, big employers and unions to embrace direct-to-account payment of wages. Through the 1960s, postal companies increasingly developed the giro system pioneered in Austria, creating the infrastructure that enabled the introduction of direct debits, standing orders and check guarantee cards, such as Eurocheque.

In the late 1950s, a push for German companies to replace the standard weekly “Lohntüte” (pay packet) with more efficient monthly paper paychecks was met with resistance from workers, who preferred cash. But many banks offered free accounts for receiving wages to entice new customers, and in the 1960s and 1970s, the number of bank branches grew steadily, and the number of households with current accounts rose dramatically. German banks agreed on a giro standard for transfers in the 1960s, enabling cashless payment transfers.

In the U.S., the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco set up the first automated clearing house (ACH) in 1972, enabling nearly instant electronic payments. In the 1970s and 1980s, U.S. employers encouraged workers to have their weekly wages paid directly into a bank account. Paper paychecks were more secure than cash, but they created traffic jams at local bank branches as people waited to withdraw their wages.

Historical check usage in the United States

Going electronic

The use of paper checks — including paychecks — plummeted as the adoption of electronic bank transfers increased and the use of debit cards rose. In the United States, check payments accounted for almost 80% of all purchases in 1995 but fell to about 45% in 2004 and just 7% in 2017.

By 2012, the Bank of International Settlements found that payments by paper check were basically nonexistent in Hong Kong, the Netherlands, Russia, Sweden and Switzerland. Paper checks still play a minor role in everyday transactions in Australia, Brazil, India, Italy, Mexico, the U.K. and Singapore. In the United States, France and Canada, use of the paper check remains notable, though it has declined significantly.

Global use of checks in decline

Digital paychecks are more secure than paper ones, and are more cost effective as well. Nacha, which oversees the U.S. ACH network, estimates that issuing a paper paycheck costs $2 to $4; issuing a digital transfer costs less than 50 cents.

The pandemic accelerated the adoption of digital payments for wages, benefits and personal consumption. 15% of workers in Latin America and the Asia Pacific region receive wages in an unconventional form, such as via prepaid debit card. But globally, most people working in the informal sector are still paid in cash. Some economies are exploring the possibilities of mobile money and cryptocurrency for wage payments.

As cashless forms of payment give way to alternative solutions in the 21st century, one wonders how long we’ll hold on to the term paycheck. Probably as long as we keep punching in.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.