If you look up at any government building in France, you’ll see inscribed on the facade: Liberté, égalité, fraternité — liberty, equality, brotherhood. That’s been a principle of French public life since the 1700s, and it’s reflected in the country’s robust social security system.

But with that robustness comes complexity. In any global ranking of countries by payroll complexity, you’ll often find France in the top spot.

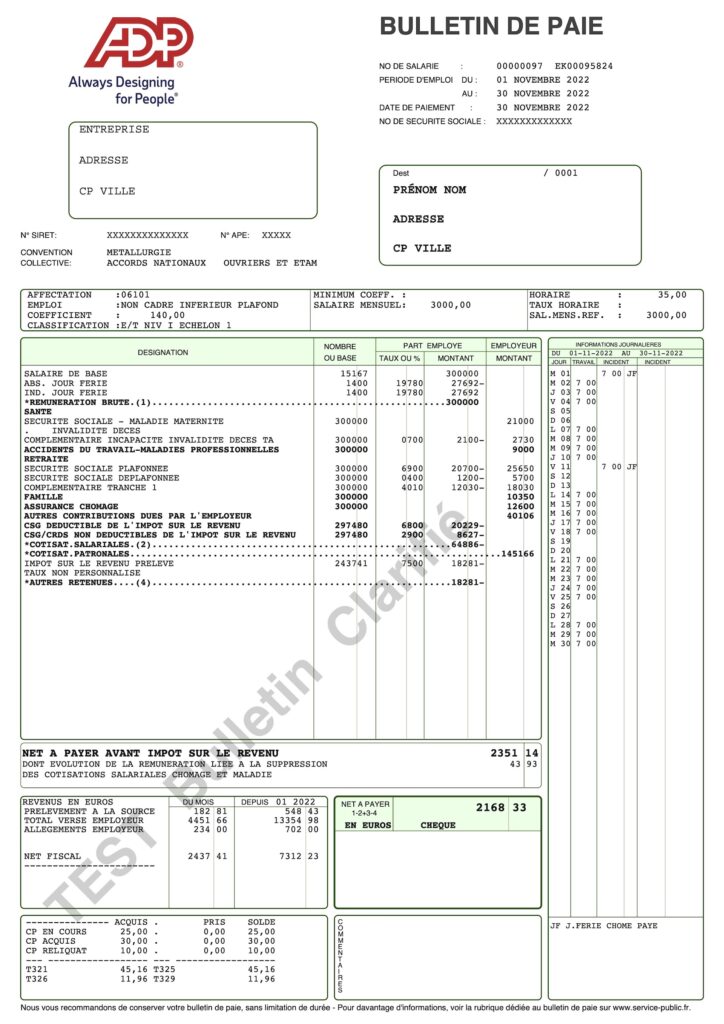

A standard payslip for French employees stretches across two A4 pages, detailing all of the contributions to the nation’s social security system, including health, maternity, disability and death funds, as well as pensions, work injury and family benefits.

Additionally, France has hundreds of collective agreements that cover many jobs in many industries, which also may have regional differences in pay or leave. In the end, France’s highly specified, orderly and transparent social security system is expressed as a complex payslip that reflects France’s economic, social and political evolution.

“In France, often to simplify means to complexify,” says Emmanuel Prévost, ADP’s Legal Watch Director for France. Since 2014, the government has been trying to reduce the number of collective agreements from about 700 to eventually 200. “In 10 years it might be more simple, but for now it is more complex as we deal with a transition period.”

One unintended side effect is that the payslip is so long that many employees don’t understand or even read them. But the details in the payslip are an important record for employers and employees alike, and are mandatory for businesses to disclose under France’s Labor Code.

“The payslips in France are so complex, nobody is able to check his own except an expert,” Prévost says.

How did it get so complicated?

The evolution of France’s comprehensive social security system tells a large part of the story of why payroll is so complicated in France.

France’s social security system is meant to be laissez-faire, but in reality it’s not, says Pierre-Cyrille Hautcoeur, an economic historian and professor at the Paris School of Economics.

The relationship between employer, employees and state with respect to social security (and worker rights) has ended up fairly prescriptive, with the government stepping in to set and update base-level contributions from each party to the social security system.

“What we mean by social security in France includes both retirement on anything earned, health, unemployment insurance, family support,” Hautcoeur says. “Most of these items are by law but frequently it’s at the firm level. There is a minimum required by law but some employers pay more. Social security is complicated because there is not only retirement, but if you become disabled, and there are different rules depending on the size of the family. There are four lines just on that.”

Minimum contributions for each component of social security is paid in varying proportions by employers and employees. For example, employees pay roughly 9% of their gross wage to Contribution sociale généralisée (CSG) or social security surcharge, while employees and employers contribute to old age insurance. Employers also contribute directly to an unemployment fund.

Then there’s supplementary pensions that are paid by both employers and employees called the AGIRC-ARRCO scheme. AGIRC is the supplementary fund for executives, while ARRCO is for general employees. Within that, there are two brackets of contribution paid in different proportions by both parties, according to Le Cleiss, a department that translates France’s social security system for international users.

Oddly, despite the government’s oversight of the social security system, French firms are meant to include their contributions as part of the cost of the labor, yet they don’t, according to Hautcoeur.

“As academics, we are surprised because you are supposed to pay a gross wage, including all of this, as the cost of labor,” he says. Over the years of employment in France, “you accumulate the right to unemployment benefits, a right to retirement.”

What workers see on their payslips each month is a record of payments under France’s public Pay-As-You-Go (PAYG) scheme, which is the primary mechanism for funding pensions. Spain and Italy have similar public PAYG schemes. Other nations use a blend of public and private, purely private PAYG or direct contributions.

“In France, often to simplify means to complexify.”

Emmanuel Prévost, ADP’s Legal Watch Director for France

France’s public PAYG system emerged out of necessity in 1945 in response to high inflation. Previously, individuals contributed to funded private pensions, but by the end of World War II those funds had lost their value, leaving nothing to pay pensioners of the time. So, in 1945, France switched from a capital accumulation financing model for pensions to PAYG, where today’s workers funded the pensions of today’s pensioners. It plays a consumption-smoothing role in the economy.

In today’s PAYG scheme, Hautcoeur says, “The pensions are paid by funds collected today from employers’ and employees’ contributions, and these are distributed immediately. And the social security system guarantees your future retirement.”

“France suffered large inflation in World War I and later in World War II — actually all the money accumulated in those funds, which was in fixed income bonds, lost most of its value. Then the only way to pay the pensions was to take it directly from the wages of employees at the same moment,” he says.

“So we switched from a capital accumulation to a PAYG system in 1945 because there was no money anymore to be distributed. To some extent these funds contributed to pay for war. So, in the end you had lots of pensioners with no income and the only way to pay for them was with a system where you transfer money directly through the system from current employees to current pensioners.”

Is the capital accumulation system a more fair or collective system than PAYG financing?

Hautcoeur says it could be argued both ways but France’s public PAYG system for funding pensions is why France doesn’t have gigantic pension funds that exist in some other markets where pensions are funded to a higher degree by private funds. An example of the latter would be the United States’ 401(k) funds that employers and employees contribute to.

“On one hand, it’s a more socialized or collective system because it’s not accumulated at an individual level. But you can also have pension funds which are organized by collective labor, at the firm level, at the national level. So the main difference is that there are no huge pension funds accumulating lots of money — which don’t exist in France,” he said.

Working in modern France

U.S. multinationals can get caught on the back foot when entering Europe, because payroll requirements vary widely among E.U. member nations, says Carlos Carvalho, President of ADP France and Switzerland.

“ADP is a school for our clients. U.S. companies often think all EU countries work the same, but they’re very different,” said Carvalho.

France recently overhauled how taxes are collected and calculated. Previously, taxpayers were taxed on the previous year’s income and could pay taxes at the end of a financial year. Then, in 2019, France moved to a Pay As You Earn (PAYE) model, or Prélèvement à la source (PAS), where employees pay taxes on income earned each month. It applies to wage earners, pensions, self-employed workers, and investment incomes.

“Three years ago there was a big tax reform in France, and an ADP representative was asked to go to the senate to explain its effects. Government policy makers asked for ADP’s input on possible changes. They asked us to road test the changes on our software so we can help them model the likely impact and effects,” said Carvalho.

Another recent change for the private sector was the consolidation of social declaration reporting in 2016. Prévost recalls that previously a company had to generate up to 34 declarations to send to 34 different recipients on a monthly, quarterly or annual basis for every employee. Now there is one central deposit point, with the information distributed to the relevant fiscal and social departments. “The spirit of the law is even more complex, and we have less time to implement it,” he says. “We are working monthly with the public administration to be able to implement legal changes.”

Collective bargaining agreements apply to about 98% of all employees in France, according to the OECD. As France is consolidating and harmonizing the collective agreements — currently they’re down to about 500 — there are transitional periods lasting a number of years where payroll professionals must be aware of both old and new rules regarding pay, leave and other benefits.

“The government tried to simplify payroll in France,” says Paris accountant and auditor Thibault Gianati. “But it’s impossible because, for example, unemployment will change, and rates will change. The government changes the tax system every year, and every two to three years there is tax reform.”

Gianati said payroll in France is further complicated by tax exemptions, some of which France implemented as a buffer to the economy during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“In the reform in summer, because of the pandemic crisis, you could pay up €3,000 without tax for social system contributions and income tax,” he says. “That was the case for many companies, but it could be up to €6,000 if there is an employee agreement, based on net income of the company. So a bonus could be non-taxed up to €6,000.”

Besides social security contributions, payslips need to account for five different types of paid leave in France, including sick leave, maternity and paternity leave, public holidays, as well as “RTT” for reduction of working time, where days of rest are allocated to employees when they work more than 35 hours a week.

Payslips also note many other common employee benefits — such as France’s staff restaurant vouchers, which have been available since the 1960s and cover about half the worker’s lunch tab, as well as employer contributions to commuting costs.

With all these contributions and deductions, in addition to variations among companies, geographies and sectors, establishing a payroll system in France can be complex and time-consuming.

“We must watch the changes carefully, because we are templating the solutions for our clients. Simplification creates complexity for us,” ADP’s Prévost says. “It’s very hard for our teams — we have to be excellent each month — but it’s easier for our clients.”

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.