Two primary monetary cultures arose over the course of human history: the Greek system and the Chinese system. The monetary system in China evolved outside of the wide-sweeping Greek influence.

China’s currency wasn’t just considered stored value but was used directly as a means of payment, in contrast to the Greeks. This led to Chinese people accepting paper currency earlier than Westerners. The earliest adoption of paper currency in China was not just due to the invention of woodblock printing in the 7th century CE, but rather thanks to socio-economic factors and people’s trust in this new system.

The earliest money

As in other countries around the world, seashells were the earliest objects used as currency in China. The vast majority of Chinese characters expressing value are derived from the pictographic character for shells (貝). The character for “poor” comes from combining the characters ”to reduce” and the number of “shells,” so that 分+貝 becomes “poor”: 貧.

As supplies of real shells were exhausted, ancient Chinese people began to imitate them using stones and animal bones, later casting them in copper. In the third century BCE, Emperor Qin Shihuang (259-210 BCE) unified China and introduced copper coins, each weighing about 16.14 grams. These small copper coins were round on the outside with a square hole inside. In the eyes of ancient Chinese people, the sky was square and the earth was round. They merged it into copper coins, symbolizing the organic unity of heaven and earth. Copper coins became a common currency that would be used for the next 2,000 years.

During the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127 CE), iron coins were used due to the lack of copper in the Sichuan province. But the large iron coins were heavy, weighing 11 kg per 1,000 coins. So if a horse was sold for 20,000 wen in coins, the money would be so heavy it would need to be transported in an ox cart. This was obviously quite inconvenient; it’s no coincidence that paper money first appeared in the Chengdu market in Sichuan province.

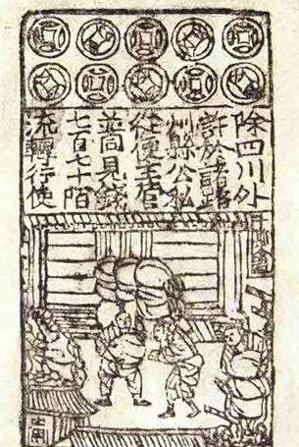

Around 1008 CE, 16 merchants in Chengdu jointly printed vouchers on paper made of bamboo bark, with patterns, passwords, markings, seals and other imprints. The denomination was temporarily filled out based on the coins paid by the recipient, and the slips were circulated as payment vouchers. The depositor delivered the cash to the shop owner, who temporarily filled in the amount of cash deposited on a roll made of paper, then returned it to the depositor. When the depositor withdrew the cash, a handling fee of 30 coins was charged for every 1,000 coins. This kind of temporary deposit voucher was called “jiaozi” or a “Chu coin.” At this point, jiaozi was a deposit and withdrawal voucher, not a currency.

As the commodity economy developed, the use of jiaozi became increasingly widespread. Many merchants jointly established jiaozi shops that specialized in issuing and exchanging jiaozi, and set up jiaozi branches in Sichuan province. The printed jiaozi pattern was exquisite, with hidden markings, black and red stamps, and handwritten inscriptions, which were difficult for others to forge. Due to the complexity of the notes and the trustworthiness of jiaozi shop owners, jiaozi had developed a very good reputation.

In order to avoid handling coins in large-scale transactions between merchants, readily convertible jiaozi was increasingly used to pay directly for goods. It was during the repeated circulation process that jiaozi gradually acquired the character of a credit currency. Later, jiaozi shop owners discovered that using only a portion of their reserves would not endanger the reputation of jiaozi. So they began printing jiaozi with an unified denomination and format, as a new means of market circulation. This type of jiaozi represented coinage, making it a paper currency. But at this time, jiaozi had not yet obtained government recognition and was still considered “private money.”

Initially, jiaozi was mainly limited to the Sichuan region, but later its use expanded to other places. Even though it was still a private enterprise until 1023 CE, the Northern Song dynasty’s court introduced extensive management requirements and policies.

Inflation issues

However, managing credit was not easy, and most people did not have the ability to guarantee it for a long time. Due to changes in economic conditions, or perhaps fraud, some wealthy merchants were unable to repay their losses, and some paper currency could not be redeemed. This triggered a credit crisis, which ended the practice of private individuals issuing jiaozi.

In the winter of 1023, the government saw that issuing jiaozi was profitable, and under the pretext of resolving continuous disputes among merchants, it officially established a ministry of jiaozi affairs and introduced fairly exhaustive regulations and requirements. The power to issue jiaozi was transferred from private merchants to the court.

The circulation period of jiaozi generally lasted from two to three years and was known as the “exchange boundary.” After the expiration date, the paper would have to be exchanged for a new jiaozi before it could be used. The reason might be that jiaozi was made of bamboo paper, which was prone to damage and forgery.

Additionally, the total amount issued for each sector was limited, and a certain reserve had to be held to ensure that the paper currency was freely convertible. The Northern Song court issued the first “official jiaozi” with the total value of 1,256,340,000 coins. This number might be due to the tradition of reserve, but its exact reason remains a mystery. The court had a capital of 360 million coins as a reserve, and the reserve ratio was 28%.

With the introduction of jiaozi, paper currency was in circulation in China six centuries earlier than in Western countries such as Sweden (1661), the United States (1692) and France (1716). This was a remarkable achievement, but it also triggered a number of financial crises.

The government quickly found that paper money was a profitable production with low costs. When there was a need for huge government financial expenditures, the government could use its power to issue paper currency without restrictions. But this would cause inflation, which led to the loss of credit attached to paper currency and turned it into waste paper.

The fate of jiaozi in the North Song Dynasty proved this. Eventually, the government no longer adhered to the fixed issuance amount for each sector, and instead issued large amounts of jiaozi. During the reign of Emperor Renzong Qingli (1041-1048), the Yizhou Jiaozi Affairs ministry issued 600 million in jiaozi in Shaanxi to pay for food for humans and horses, without maintaining any reserve.

Previously, the regular reissuing of paper currency had created a barrier to inflation because the new currency value was pegged to the old currency it was replacing. However, the government’s abuse of credit eventually led to jiaozi becoming a tool for accumulating wealth. Without reserves, jiaozi lost its circulation function and its value.

Later developments

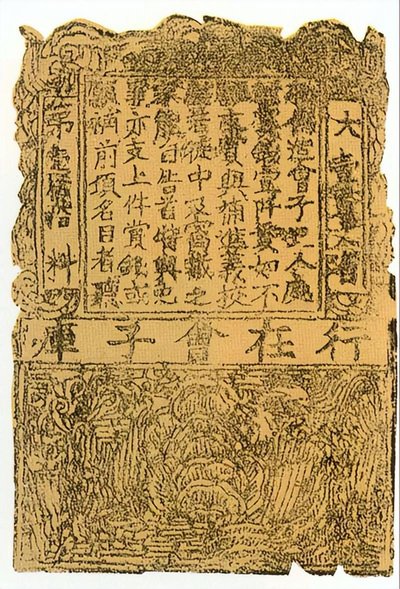

After the Northern Song Dynasty was destroyed, the Southern Song Dynasty was established. The paper currency issued in the Southern Song Dynasty, known as bianqian huizi or “convenient money association,” were used as bills of exchange, checks, and other instruments. In the later period of the Southern Song Dynasty, a huge number of banknotes were issued, causing severe inflation. During this time, paper currency was practically worthless.

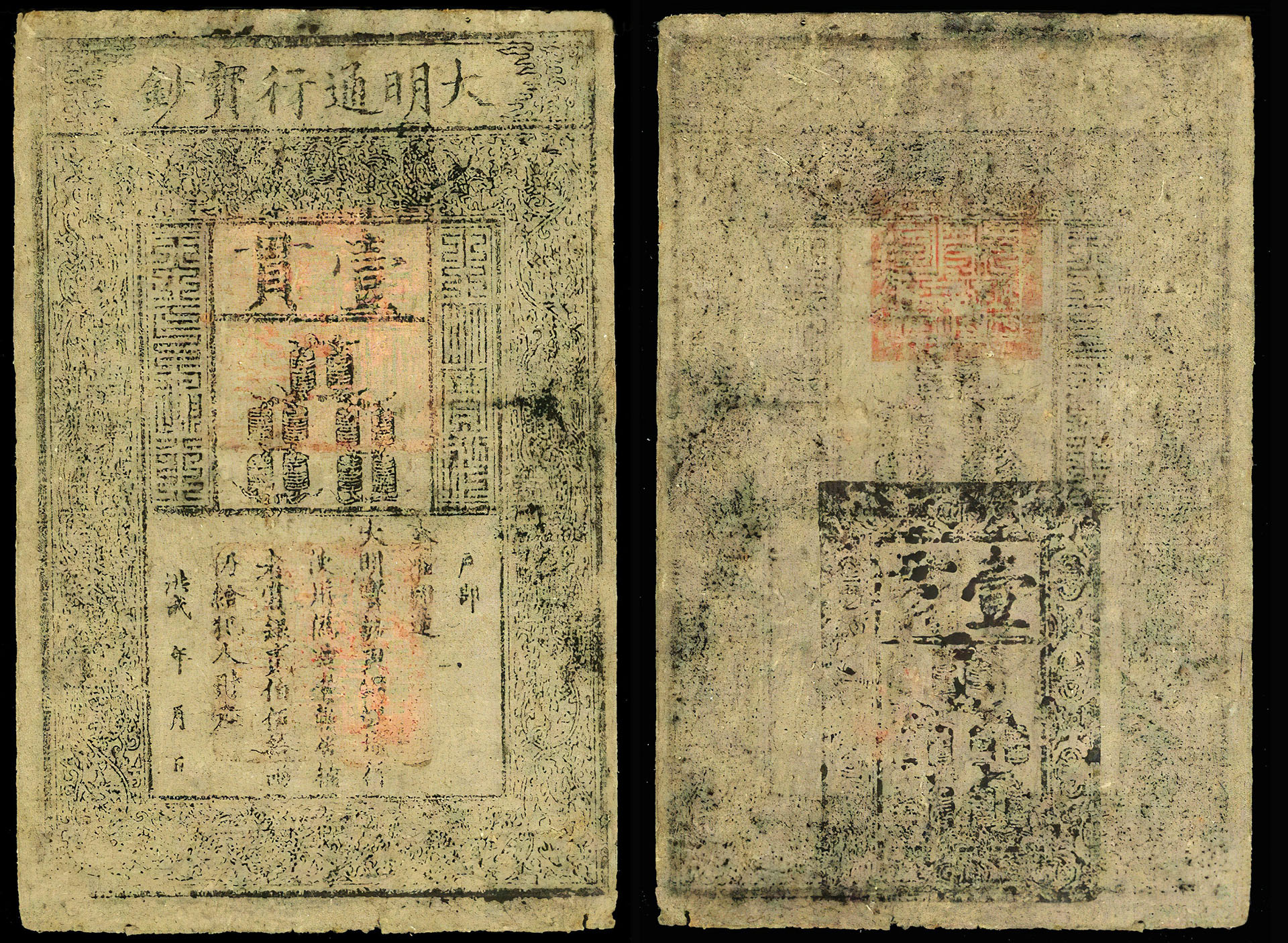

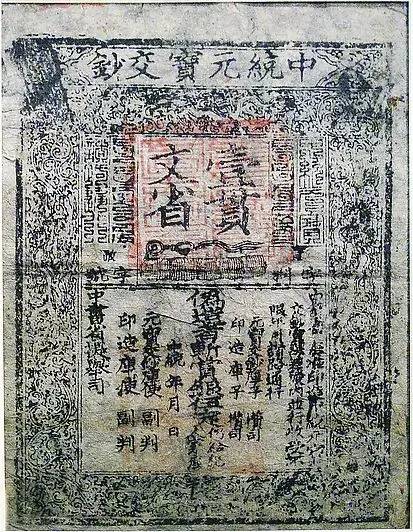

Finally, Kublai Khan of the Yuan Dynasty issued paper money in 1260 that offered a reprieve from inflation. Based on silver and accompanied by sufficient reserves and strict control over issuance, it became the most stable and complete paper currency to date. It also became the common currency in Korea, Vietnam, Thailand and elsewhere. However, in the late Yuan Dynasty, the reserve funds for paper currency were misappropriated, and the issuance increased, ultimately leading to hyperinflation.

The history of paper money in China demonstrates the currency’s dual nature. It could greatly facilitate daily commodity transactions, but, without appropriate regulation, it was easy for issuers to recklessly issue currency, transfer losses, and gain profits through inflation.

During the mid-1300s, the Ming Dynasty came to power, followed by the Qing Dynasty from the mid-1600s to the early 1900s. These dynasties witnessed a large influx of silver into China, and silver currency came to dominate economic life, competing with copper coins.

For several centuries, the problem of inflation due to paper money was kept largely at bay. However, during the late Qing Dynasty, following the Taiping Rebellion (1851-1864), the government collapsed and paper money was once again devalued by massive inflation. But by then, inflation or not, paper money was here to stay.

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.