The year 1946 was an important one. The planet was starting to recover from World War II. The United Nations held its first General Assembly. The first programmable digital computer, the ENIAC, was put into service. And it was the start of the Baby Boom.

The increase in births between 1946 and 1964 in many places around the world created the largest generation to-date: the Baby Boomers. Today, the oldest Boomers are 75 and the youngest are 58, with retirement on the horizon.

The average world life expectancy in 1960 was just 52.6 years; in 2020 it had increased more than 20 years, to 72.7 years. With increasingly older populations, the pension systems in many countries are facing challenges in the coming decade.

A country’s wealth is a key indicator of longevity, and high-income countries have the largest populations of people over age 65.

How the world is aging by country income, 1960-2020

But the gap in life expectancy between poor and rich countries has narrowed in the past 60 years — from 29 years in 1960 to 17 years in 2020.

Life expectancy by country income, 1960-2020

Around the world, most statutory retirement ages are between 60 and 65, but some countries are increasing this to 67 or older to take into account increases in life expectancy. Anecdotally, we’ve found that many 75-year-olds are still working part-time, whether to pad their bank accounts or to combat boredom. Like Dolly Parton, Cher, Steven Spielberg and Barry Gibb, all born in 1946, many are staying active in their retirement years.

We talked to eight 75-year-olds around the globe to see how they’re doing in retirement.

Sources: 2020 data from the OECD, United Nations and World Bank

Australia

Australia has a unique retirement system, with a government age-based pension plus employee-funded savings called superannuation, or just “super.”

POPULATION

25.7 million

MEDIAN AGE

37.9

POPULATION OVER 65

16.3%

GDP PER CAPITA

$54,654

Jenny Phillips

SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA

I partially retired at the age of 50, when I moved from Sydney back to Melbourne to look after my parents, who were getting on in years. I took a part-time job doing food demonstrations in supermarkets. I enjoyed it because I was always meeting people. I did that for about 10 years. After my parents died, my husband and I returned to Sydney in 2016. My three kids were there, and we were forever going up and back to see our young grandchildren.

I love being retired. I have the freedom to choose how I spend my days. I don’t have to get up every morning and work from 9 to 5. I’ve done all that stressy stuff already. That said, my life at the moment is full on, because I get involved in things!

I volunteer at my granddaughter’s school canteen and am helping to organize the principal’s awards. I also volunteer at a foundation that provides meals to people who are homeless or disadvantaged. Volunteering keeps me grounded. People come to us carrying two or three bags that are probably the sum total of their possessions. Seeing people who don’t have anything makes me realize that I have a lot.

My husband and I are not millionaires, but we’ve got more than enough money. We can afford a comfortable lifestyle. We saved for our retirement through superannuation contributions. We also get a small pension, and because we are part pensioners, we are entitled to get discounts on things such as regional travel and water rates.

I am content. I’ve visited some lovely countries, and have done a bit of business-class travel. Three countries that I’d still like to see are out of bounds: Syria, Iraq and Iran. I’m just about to go to Libya. My daughter and her family will be there before I arrive. I’m flying there on my own, but my son-in-law, who is Libyan, will meet me in Tunisia and fly back to Tripoli with me. After I booked the tickets, I lay in bed that night and thought, “Jenny Phillips, what have you allowed yourself to be talked into?” Then my more adventurous side kicked in and I thought, “Yeah, let’s go.” — as told to Jessica Mudditt

Colombia

South America’s third-largest economy joined the OECD in 2020. Colombia’s retirement ages are 62 for men and 57 for women.

POPULATION

50.9 million

MEDIAN AGE

31.3

POPULATION OVER 65

8.5%

GDP PER CAPITA

$14,999

Nubia García

BOGOTÁ, COLOMBIA

I worked for 30 years, and now I’ve been retired for nearly 30. I started working at the Central Bank of Colombia as a commercial secretary in the payment office. My boss was in charge of payroll, which went out every 10 days. I liked my job. By the time I retired in 1993, I was training personnel.

I honestly didn’t think about saving for retirement when I was young. As a woman, at that time, you’d enter the workforce knowing that when you got married, you’d have to stop working. I was lucky, because they changed that company policy in 1963.

While I was working, I bought an apartment, a car and other things, but when I got divorced and became a single mother of three, I had to sell everything in order to support my children and give them an education.

I was very lucky I got a pension from the Central Bank of Colombia. Although if I hadn’t had that, I would’ve found a way. Inflation has changed the amount I receive over the years. But now I get about 4 million Colombian pesos ($1,020) every month after deducting the payments for my health insurance and housing loan.

The money I get from my pension isn’t a lot, but it’s enough to have a comfortable life — without luxury but comfortable. It is enough for one person, and right now I’m also helping family members who need support.

When I retired, I thought for a long time that I would go back to work, but I have never gotten bored. I do as I wish. I like wandering around the city. It was difficult during the pandemic because I couldn’t do that anymore, but I found ways to keep living. I am staying with my daughter and helping take care of her two children. But I do miss being completely independent in my own space. If my children are well and we all have good health, that’s all I want. — as told to Erika Piñeros

Iceland

The Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Index rated Iceland’s retirement system the world’s best in 2021.

POPULATION

366,000

MEDIAN AGE

37.5

POPULATION OVER 65

14.6%

GDP PER CAPITA

$55,213

Einar Gylfi Jónsson

REYKJAVIK, ICELAND

I worked as a psychologist for more than 40 years before I retired two years ago. Before I retired, I worked part-time for some time due to my wife’s health. I realized when I retired, it was going to be a great experience to have fewer obligations. It’s great to be almost always available when my kids or grandkids need me.

I feel financially secure, and I’m very grateful for that, that I have no financial worries. I paid into a pension during all my working years. You’re required to pay at least 4% of your wages into a pension fund in Iceland. You can choose the pension fund in the private sector, and your employer pays the same amount into the fund. Before I fully retired, we sold our apartment because it was too big for us at this stage of life. We moved into an apartment building for people over 60, so we don’t have a mortgage to pay. The money from my pension is 472,000 Icelandic króna ($3,600) after taxes each month. That is more than enough for me.

I haven’t taken any side jobs in retirement. I’m not the type of guy who can take a job and work a little and not think about it. I’m an “all in” type of person. Also, because of the nature of my work, I would have to have an office. So I’ve been enjoying this new role of not having a role. I’m writing a little for myself; I love to travel alone around Iceland. Men tend to define ourselves so much in our work, and it’s a status symbol for an Icelandic man to be very busy. I’ve been enjoying having more time for my children and grandchildren instead of the demands of work and punctuality. I’m trying to be less punctual — only when it’s necessary. — as told to Jenna Gottlieb

Japan

With a population that has the oldest median age in the world, Japan has raised the retirement age to 65 for government workers and 70 for others.

POPULATION

125.7 million

MEDIAN AGE

48.4

POPULATION OVER 65

28.8%

GDP PER CAPITA

$42,939

Atsuko Hirose

KAWASAKI, JAPAN

I started working at age 18 as a clerk at the Kanagawa Prefectural Police Department. I worked there for eight years and left when I married my husband and devoted myself to raising my three children for a while. When they were grown, about 30 years ago, I was invited by a friend to join the Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation, and I worked as a telegram operator for three or four days a week, for a few hours a day.

It was fun to make friends at work and feel that I was participating in society. I retired at the age of 60; the current retirement age in Japan is 65. The Japanese economy was booming at the time, so I was quite optimistic that my life after retirement would be enjoyable.

But I was sad when I retired, because I had become friends with so many people, and I envied the younger people who continued to work. It was hard not to be able to talk to my colleagues. I liked working with a computer, so I bought a PC for myself, but it was boring since I didn’t use it for work.

So I visited Hello Work, the Japanese government’s employment service center. But the only job available was full-time, which did not suit my needs. After that, I registered with the Japanese public employment service for seniors and got a job where I could use a computer. I have been working at a warehouse company in Kawasaki City for about four days a week for the past 15 years. My job includes making stickers for machine parts made in China and putting postcards into plastic bags.

Since I turned 60, I’ve received about ¥5,000 ($44) per month from my national pension. I also receive about ¥80,000 ($700) in social security once every two months, and my work pays ¥50,000 ($438) a month. My husband earns more than I do, and our 45-year-old son lives with us in our house in Kawasaki City. My physical strength is decreasing, and my movements are getting slower, but I want to continue working as long as possible. I enjoy spending time with my five grandchildren and traveling in Japan and overseas to experience nature. — as told to Taro Karibe

Pakistan

The fifth-most-populous country in the world implemented a wide-sweeping social security program in 2019.

POPULATION

220.9 million

MEDIAN AGE

22.8

POPULATION OVER 65

4.3%

GDP PER CAPITA

$1,193

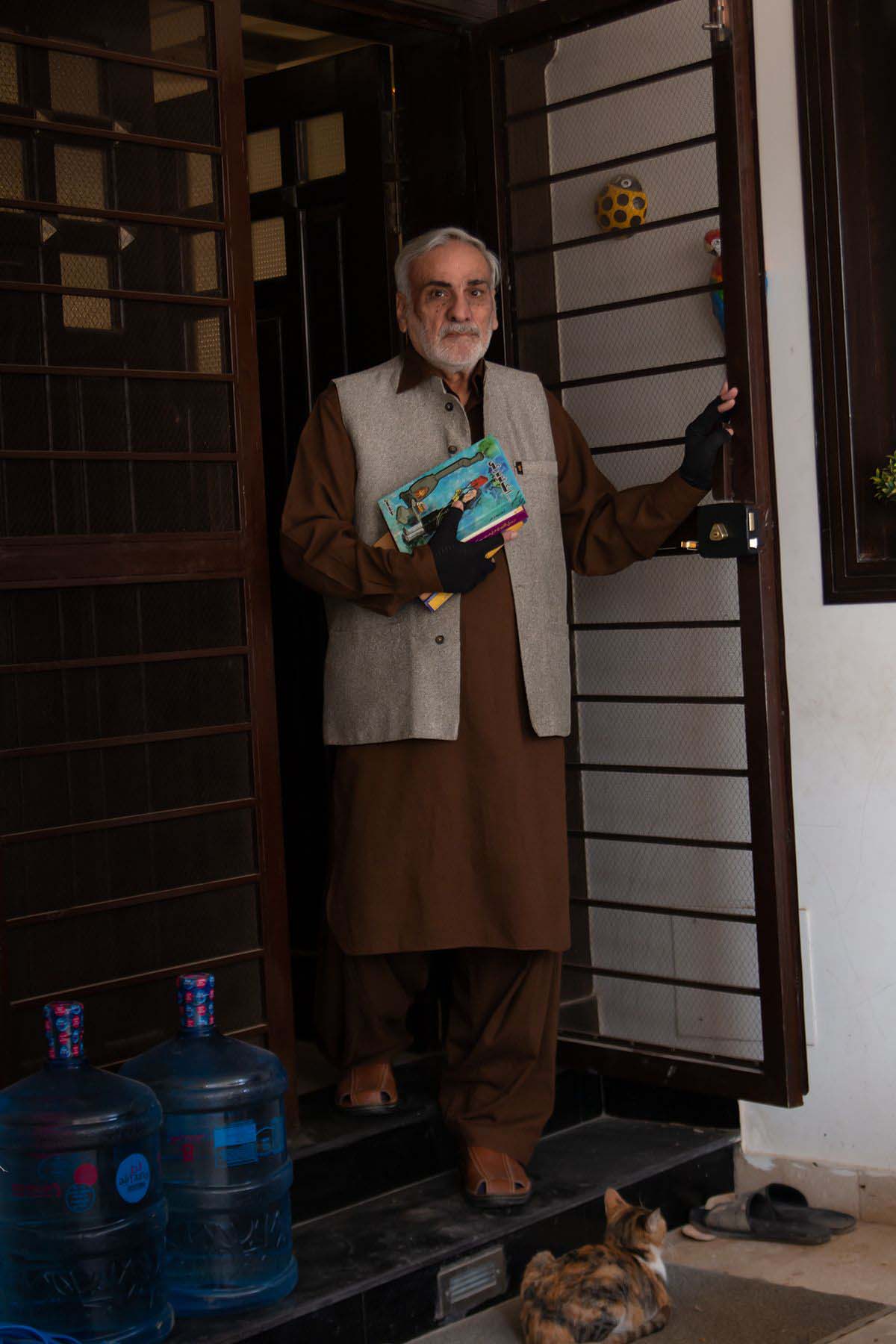

Syed Shaukat Jamal

RAWALPINDI, PAKISTAN

I was born in Munger district in Bihar state in eastern India. My father was a journalist working in the metropolitan city of Karachi. After the partition happened between Pakistan and India, my family and I also moved to Karachi.

After finishing grade 10 in 1961, I moved to Lahore in the north of Pakistan and found some administrative jobs. In the early 1970s, I worked for Pakistan International Airlines and then landed an administrative job in a private company in Saudi Arabia, and I lived there for the next four decades. My wife and I raised three sons and two daughters in Riyadh.

My job was very interesting; it was multifaceted with annual pay increments and many added benefits, like health, car and housing allowances. It was very secure. I was never scared that I might get fired.

In the beginning, I didn’t give my post-retirement plans any heed, but as I aged, I started investing and looked forward to the gratuity I would get at the end of the service. Otherwise I didn’t have any retirement plans. One needs to make investments in one’s youth to have a better old life.

Working abroad was not very easy. A lot happened when I was away from Pakistan, both celebrations and tragedies. My parents died, my siblings died, and I couldn’t spend time with my loved ones. But for those sacrifices, I am glad I have a healthy life and all my kids are educated. They all are married and happy.

My wife and I now live with one of our sons and his family in our own house. My living expenses are about 150,000 Pakistani rupees ($850) per month. When I worked in Saudi Arabia, I bought some properties in Pakistan. When I moved back at the beginning of 2021, I sold some properties, bought a house and invested in others to keep my money rolling.

My daily routine now consists of reading, going for walks, watching TV and writing my poems. My father knew Urdu, Persian and Arabic and loved poetry, too. I got my interest in poetry from him. I have written five Urdu poetry books, the first of which was published in 2000 and the latest in 2019. I wish to spend as much of my time as possible with my family — and to write poetry for the next generation. — as told to Annam Lodhi

Russia

The retirement age is currently 61.5 for men and 56.5 for women, but Russia is raising those ages to 65 and 60, respectively, by 2028.

POPULATION

146.2 million

MEDIAN AGE

39.6

POPULATION OVER 65

15.7%

GDP PER CAPITA

$28,220

Vladimir Studennikov

ST. PETERSBURG, RUSSIA

My life is good. I live in a one-bedroom apartment in Kupchino, south of St. Petersburg, with my wife, who is a retired historian and museum worker.

After I retired in 2006, when I was 60, I began receiving my pension but didn’t spend it. I worked as a co-director, made two documentaries, and went on expeditions with different film crews. With the Covid-19 restrictions I’m forced to self-isolate, so I haven’t been working since March 2020.

I ended up in the artistic sphere by chance. After school, I went to a medical college and worked in the artillery academy in Leningrad. I had been working at the electrotechnical department there for four or five years and didn’t plan any changes. But my then-girlfriend convinced me to join her on a trip to Yaroslavl, northeast of Moscow, as she planned to enter a theater school there. I joined her, passed all my exams and was accepted to my own surprise!

After graduation, I worked as an actor in the Vorkuta State Drama Theater for about three years. Later I came back to Leningrad and joined the Lenfilm studio in 1978, the second largest in the Soviet film industry. I worked as an actor, filmmaker’s assistant, then as a co-director.

I wasn’t really preparing for my retirement. I was just saving money because my salary was high in the years before I retired, equivalent to about $1,000 per month. I didn’t even plan to buy my own apartment. I lived in the communal flat where I was raised, and it was fine. It had just three rooms, one of which I inherited from my mother.

Then I met a lawyer during some filming. We chatted about our lives, and she was surprised with my housing situation. She was eager to help and connected me with a reliable realtor. I privatized my room, sold it and put that money and my savings into renovating our own flat.

Back in 2005, I paid about $25,000 for our one-bedroom apartment of 40 square meters. These days, that type of flat costs about $66,000. Before the pandemic, I was earning a monthly salary of 35,000 rubles ($462) from my film and TV work, plus some compensation from the state for my utility bills. My pension is 17,000 rubles ($224) per month, but my breadwinner is my wife. Together we have about 70,000 rubles ($924) each month, which is perfect for us. — as told to Elena Bobrova

United States

The retirement age in the U.S. is increasing from 65 to 67 for people born in 1960 and later, but people who wait until age 70 receive higher monthly payments.

POPULATION

329.5 million

MEDIAN AGE

38.3

POPULATION OVER 65

16.9%

GDP PER CAPITA

$63,285

Albert Guffanti

MIAMI, FLORIDA, UNITED STATES

I still work as a lawyer, as I have for 46 years, and plan on doing so for the foreseeable future. I flunked chemistry, so I couldn’t be a doctor — joking, joking.

Law has provided me with a good life to provide for myself and my family. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve taken fewer cases in the courtroom and more in appeals that I handle from my home office, although I still find myself in the courtroom from time to time to help other attorneys, and I still field calls from judges. I always enjoyed being in the courtroom and the uncertainty it had, but I find it better to just work from home now.

Even with this, I’m still working nearly every day into my 70s. Most of the work I’m doing is in parental rights, criminal defense and dependency, things of that sort. The work itself has been memorable. I’ve helped overturn local legislation that I saw as unfit for law. I’ve acted as the lawyer for a few small bands and helped them sign contracts, and the people I’ve met through defense were definitely interesting.

Before I broke into law, I was a member of the U.S. Air Force during the Vietnam War. In Vietnam, I served as a radio operator and helped direct airstrikes to plumes of smoke. I rarely got on the plane, but it was an experience when I did.

Vietnam itself was memorable, but one moment that sticks out is the time we were attacked on base. Everyone was in the mess hall to watch “Dirty Dozen,” but I had already seen it, so I went back to my bunk. That was when grenades and rockets hit the base. I dove under my bunk during the attack. I didn’t put in for a Purple Heart because all I did was scrape my knee.

My time in the military allowed me the chance to do my schooling, using my GI Bill benefits for everything I could. As I’ve gotten older, I just want to appreciate my time. I’ve paid into a SEP IRA and have enough to live comfortably. At this point, I just like to keep things simple. I play Pac-Man, shoot some hoops and play ping pong. When I’m thinking about my time, I realize I just want to live the next 10 years. — as told to Tim Becker

Zambia

This southeast African country, known for its copper industry, has one of the world’s youngest populations.

POPULATION

18.4 million

MEDIAN AGE

17.6

POPULATION OVER 65

2.1%

GDP PER CAPITA

$1,050

Read more

Sign up to keep up to date with ReThink Q.